By Gus T. Renegade

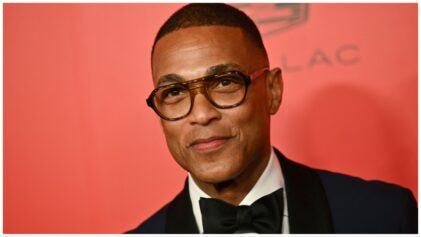

It’s not Moby Dick. It’s not Tom Sawyer. The most popular figure in the history of American literature is Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom. This 19th century hero has been routinely invoked during the Baltimore upheaval of 2015. Many of the most scathing critiques of the reporting of CNN’s Don Lemon and the response of President Barack Obama referenced Stowe’s creation. Tragically, our opposition to white supremacy often replicates the narratives and concepts of our oppression.

The fundamental, recurring plot of racism is harm to Black people. Third-generation physician and author Dr. Frances Cress Welsing submits that our reflexive response to racism is not an insatiable hatred of white folks, but to blame and attack Black people. Racists condition and reward us for targeting our frustrations on Black people.

Minnesota state Rep. Ryan Winkler, a white Democrat, restricted his angst regarding the 2013 Supreme Court ruling on the Voting Rights Act to one person, Justice Clarence Thomas. Winkler branded Thomas an “Uncle Thomas.” White people model and encourage blaming Lemon, Justice Thomas, any and all Black people because they grasp the allure and impotence of this strategy. Verbally chiding or even physically disciplining “sellout” Black people –“race traitors” – does not boost the value of Black lives or vanquish racism.

Counter-racist scholar and author Neely Fuller Jr. follows the logic: “Just get rid of all these “Uncle Tom” Black people, and then all of a sudden white people with the rest of us [Blacks] who are not ‘Toms’… now we got everything going for us?”

Fuller labels this fantasy and our counterproductive predisposition to focus on and fight with other Black people as Racial Shadow Boxing. From the battle royal of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man – where white men orchestrate a homoerotic orgy featuring blindfolded Black boys pummeling each other – to boxers Manny Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather, racists celebrate, televise and are nourished by melanin-rich people blaming and battering each other.

The graves of NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers and author and South African apartheid combatant Steve Biko remind us that confronting white folks is dangerous, potentially fatal. Lambasting “Uncle Toms” is not.

Whether repairing a leak at home or permanently dismantling white supremacy, getting to the source solves problems. So-called “Uncle Toms” are not the root of racism. University of Texas (Austin) professor and author Dr. Robert Jensen makes it plain: “The problem is white people.”

Because the global white race has more power than the global Black collective, they can easily force, manipulate, threaten or mandate that Black people function against our individual or collective Black interest. Steve McQueen provides an Oscar-winning illustration with 12 Years a Slave; Solomon Northup’s character is ordered to lash another enslaved Black person. White race soldiers commanded Black inmates to brutalize Mississippi warrior Fannie Lou Hamer. This is what white domination looks like.

And from the looks of things, we can’t impede the production of “Uncle Toms.” Malcolm X rebukes of 1960s “Toms” have sizable YouTube real estate, but fail to eliminate racism or the “Uncle Toms.” Fuller suggests that Black people consider and accept that racist women and racist men can produce “Uncle Toms” faster than Black people can “hold them accountable” or “Drop Squad” them.

As the world scrutinizes the Baltimore unrest and homicide of Freddie Gray, many reflect on a 1994 satiric flick where a band of militant African-Americans devote their counter-racist offensive to “Uncle Toms.” In Drop Squad, abducted “Toms” are kidnapped, stuffed into a van, not buckled in and subjected to Abu-Ghraib-style torture.

No white people were harmed in the making of this film.

… And our opposition to white supremacy often replicates the narratives and concepts of our oppression.

Fuller reports that there is an irrefutable record of disaster in every attempt where Black people have “[gone] after the ‘Toms.’” He submits this metaphor: “It’s like turning on a faucet and then grabbing a mop. You’ll be mopping forever.”

Racists flood our horizon with images of disreputable Black people. Racism makes the abuse of Black people seductive. Racism makes the abuse of Black people one of the most promoted, accepted concepts in the universe. Black people are always to be blamed, habitually convicted, occasionally executed. But always blamed. Freddie Gray broke his own spine. Al Sharpton obstructs the gates to Black liberation. Holding “Toms” accountable is familiar, might even “feel” gratifying and constructive. But the evidence is unambiguous, conclusive: putting “Uncle Toms” on blast has no impact on white folks.

Fuller concludes that, “If all [“Uncle Toms”] fell dead immediately, the condition of Black people would not change.”

Unfortunately, the concept of an “Uncle Tom” nemesis has become a potent, time devouring conviction. Undoubtedly, many readers remain convinced of the need to castigate – perhaps purge – “Toms.” Winkler and some whites may support the call to arms. Before commencing the obligatory Tom-hunt, there should be a clear articulation of what qualifies one as an “Uncle Tom.”

Fuller says that mirrors shred his enthusiasm for defining and identifying “Toms.” His reflection reminds him that unless a Black person can move uninhibited throughout the universe without answering or submitting to white folks, he or she might be a “Tom.” As this author and few readers are completely independent and defiant of whites, perhaps we should practice revolutionary patience and empathy with other Black people and ourselves. As opposed to chastising how other hostages of racism respond, we can demand Black excellence and improvement from the person in the mirror.