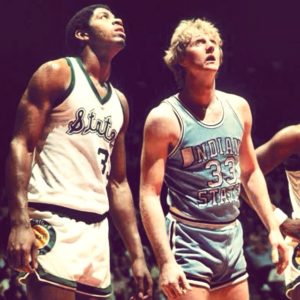

Magic was a phenomenon, a 6-foot-9 point guard. Bird was a curiosity, a white forward who played like a brother, albeit it mostly on the ground.

It was something hardly ever seen in a championship-deciding game: the best two players in the country going head-to-head. Hakeem Olajuwon and Patrick Ewing, of Houston and Georgetown, respectively, would it bang out in 1984 in a matchup of titans five years later, but it was not the same.

But Magic and Bird were different. In a real sense, both were mysteries. They were read about, but hardly seen. Their games were not broadcast as games are now, so there was only a hint of what they could do, not a visual portfolio.

So, the anticipation for that game was immense. In today’s world, with multiple sports channels that air 24 hours and social media, the hype would have reached the stratosphere.

But the game enjoyed immense hype by 1979 standards, and while the game itself did not match the build-up in drama—Magic’s Michigan State beat Bird’s Indiana State, 75-64—a lot came out of it. Johnson dazzled in ways never before seen—a man that big, that agile, leading the fastbreak, dishing to open teammates. . . and smiling the whole time. He permanently changed the idea of a point guard.

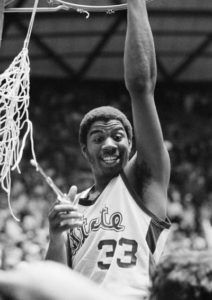

Greg Kelser, a forward of supreme athleticism, would burst upon the scene, throwing down dunks on the break that Johnson created for him.

Bird, a self-described “Hick from French Lick,” a small rural Indiana town, flashed the brilliance that would become commonplace in the NBA. But he did not shoot the ball well, and later said that game took years to get over because he wanted so badly to impress in that forum.

It seemed the entire sporting world watched. The game scored a 24.1 rating—the second-highest for a sporting event in history, college or pro.

So many watched, certainly, because of the buildup of Black vs. white. Magic vs. Bird. Us vs. them.

Black, Magic, “We” won, which helped solidify Johnson as one of the all-time greats. What he did in the NBA was spectacular and what people remember most. But that game 36 years ago was the beginning. He had been called Magic, but he became Magic that night.

It was a night that many regard as the most influential in basketball lore. It introduced the world to a pair of the all-time best, players who could make others better, who were clutch, who were winners, who had charisma, even if they were polar opposites.

Their rivalry carried over to the NBA, where they resuscitated a league that was mired in poor ratings—games were not even shown on live television. Poetically, they led their teams to the NBA Finals and crafted head-to-head matchups that millennials who were not around then would have loved.

A few years ago, Magic said of Bird: “We’re mirrors of each other. I may smile a little bit more, but the way we play the game of basketball was exactly the same because we would do anything to win. We didn’t care about scoring points. We cared about winning the game and making our teammates better. That’s why we were able to change not only (college) basketball but able to change the NBA, too.”

Six months after the ’79 Final Four, ESPN launched. It rode the momentum of Magic and Bird and survived by airing college basketball games around the clock. Eventually, March Madness was elevated to an esteemed level, one that just did not have the panache before Magic and Bird.

Now, every game during the NCAA Tournament is aired and March Madness is a multi-billion-dollar brand that exposes dreams realized of young athletes—all a byproduct of what happened 36 years ago today.