State officials were hoping racial disparities would improve with the legalization of weed. They did not, according to the study.

In fact, the report examined drug arrests in all 64 Colorado counties for two years before and two years after legalization in 2012, and the numbers were not positive for African-Americans.

They showed that marijuana arrests in Colorado virtually stopped after voters made the drug legal in small amounts for those 21 and older. But the arrests did not stop for African-Americans.

Blacks were more than twice as likely as whites to be charged with public use of marijuana, the report said. Blacks were also much more likely to be charged with illegal cultivation of pot or possession of more than an ounce.

Last year, when Colorado’s recreational marijuana stores opened, Blacks were 3.9 percent of the population, but accounted for 9.2 percent of pot possession arrests. And for illegal marijuana cultivation, the disparities increased even more.

In 2010, whites in Colorado were slightly more likely than Blacks to be arrested for growing pot. After legalization, the arrest rate for whites dropped dramatically but heightened for Blacks. In 2014, the arrest rate for Blacks was roughly 2.5 times higher.

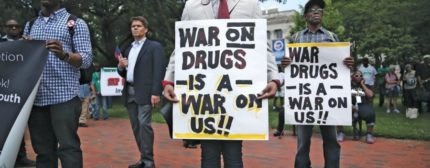

These numbers reflect an ongoing targeting of Black people by law enforcement.

“Legalization is no panacea for the longtime issues that law enforcement had with the Black and brown community,” said Art Way, Colorado director for the Drug Policy Alliance.

Overall, there was a drop-off in arrests in Colorado, said Tony Newman, of the Drug Policy Alliance. The report said that the total number of charges for pot possession, distribution and cultivation plummeted almost 95 percent, from about 39,000 in 2010 to just over 2,000 last year.

“Despite the unsurprising racial disparities, these massive drops in arrests have been enormously beneficial to people of color,” Newman said in an article published by The Guardian.

The analysis did not analyze data for Colorado’s largest ethnic minority, Latinos, because data comes from the National Incident-Based Reporting System, which does not tally numbers for Latinos.

Despite the blatant numbers, Tom Gorman of the Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area program, insisted that officers are not racially profiling pot users.

“Racial disparities exist in other laws. What does that mean, that homicide law, rape laws, weapon laws are racist? There are other factors going on here that we need to address,” Gorman said.

After legalization, racial disparities did ease somewhat for marijuana distribution charges. Blacks accounted for about 22 percent of such arrests in 2010 and around 18 percent in 2014.

“The overall decrease in arrests, charges and cases is enormously beneficial to communities of color who bore the brunt of marijuana prohibition,” Rosemary Harris Lytle of the local NAACP said in a statement.

“However, we are concerned with the rise in disparity for the charge of public consumption and challenge law enforcement to ensure this reality is not discriminatory in any manner.”

Similar racial disparities in Washington state have been uncovered, too. Last September, Seattle’s elected prosecutor dropped all tickets issued for the public use of marijuana through the first seven months of 2014 because most of them were written by a single police officer who disagreed with the legal pot law.

About one-third of those tickets were issued to Black people, who make up just 8 percent of Seattle’s population.

A researcher who did not work on the Drug Policy Alliance report, sociologist Pamela E. Oliver of the University of Wisconsin, said the numbers reflect greater law enforcement attention paid to Black people.

“Black communities, and Black people in predominantly white communities, tend to be generally under higher levels of surveillance than whites and white communities,” she said in an email to The Guardian, “and this is probably why these disparities are arising.”