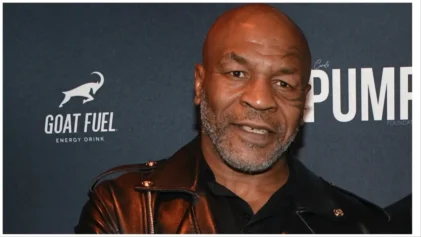

That was the magnitude of “Iron Mike”—he was the first heavyweight boxer since Muhammad Ali to command even non-boxing fans’ attention. Ali did it with commitment and consciousness outside the ring; Tyson did it with brute force inside it.

Black kids from impoverished backgrounds looked at the former heavyweight champion’s success as a touchstone, tangible evidence that even if they could not kick butt like Tyson, he was out there doing it for them.

So powerful and destructive was Tyson in becoming the youngest heavyweight champion at 20 years old that he inspired fear in his opponents. From Trevor Berbick to Michael Spinks and most anyone else who faced him, their terror was palpable. They were defeated before Tyson even entered the ring in his trademark black shorts and boxing shoes.

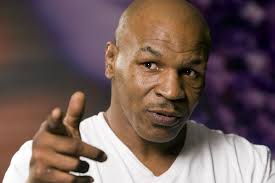

Then came February 11, 1990. The center of the athletic world was in Orlando, FL, where the NBA All-Star weekend was taking place—not in Japan, where Douglas, still grieving the recent death of his mother, was a 42-1 underdog. The only mystery about the fight was how long it would last before Tyson crushed Douglas.

When word first reached Orlando that Tyson not only had lost, but had been knocked out by this “Buster,” people considered it an early April Fool’s joke. Only it was the truth, a truth neither Tyson nor boxing ever overcame.

A Douglas left hand in the 10th round at the end of a barrage of punches knocked Tyson silly and sent him into a tailspin that broke the hearts of the young Black fans in general and supporters from his Brownsville section of Brooklyn in particular.

He would never get his legs after that loss. His drinking and cavorting increased, according to Rory Holloway, who served as a Tyson handler during that time. Holloway has written a book called, “Taming The Best: The Untold Story of Mike Tyson,” and he goes through great lengths describing the dysfunction that he says toppled Tyson.

“I knew it would catch up with him, and it did,” Holloway said to the mirror.com. “I don’t think there is a single person alive who could’ve changed the outcome.”

Holloway wrote of Tyson’s resistance to training after the Douglas loss and his insistence on women and eventually drinking and drugs.

Tyson won four more times, more on his reputation and inferior opponents than his preparedness. And then he was convicted of raping Desiree Washington, a beauty contestant, in Indianapolis.

Holloway said: “The rape case was inevitable. I’m surprised more girls didn’t make claims against him.”

Tyson spent three years in prison, a stint that Holloway said did little to rehabilitate him. Meanwhile, boxing was in a prison of its own. Without Tyson to carry the sport, it waged on with noble champions like Evander Holyfield and Riddick Bowe, but neither of them combined moved the interest meter like Tyson.

Released from prison, Tyson was a shell of the tactically savvy boxer he was before legendary trainer Cus D’Amato died. He eventually was stopped by Holyfield and in the rematch, reached the depths of his career by biting off a piece of Holyfield’s ear in a disqualification.

“That’s the frustrating thing,” Holloway said. “We only saw the tip of the iceberg of what Mike is capable of. If he hadn’t had the distractions he could have been the best of all time. He had the charisma, the physical ability and the talent to put him in the same category as Muhammad Ali (as a boxer).”

Tyson’s unfilled promise dates back to 25 years ago today, to Japan, to Buster Douglas. In his stupor on the canvas, Tyson aimlessly scrambled to pick up his mouthpiece. He has been scrambling ever since.