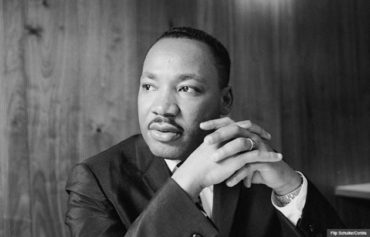

We have witnessed months of activists and protesters filling the streets in a rage-induced movement that borrows many of its moves and motives from the highly educated Baptist preacher who stood toe-to-toe with presidents. Indeed, the details of King’s relationship with President Lyndon B. Johnson have become a matter of national debate because of director Ava DuVernay’s powerful depiction in the film Selma of the Selma-to-Montgomery marches that King engineered, as if a conference of obscure history academicians had moved from C-Span to the lead story on the top of every news site in the land.

Even 50 years after the events transpired, the takeaway from the LBJ tempest was clear: Go after our white heroes and we will take you down.

As the movie Selma and about a thousand books have made clear, King was a master strategist. He was always at least a couple of steps ahead of the racists with whom he was doing battle in the South—and perhaps the ire of the LBJ adherents was raised because Selma showed him as being a step or two ahead of the president, too.

It all raises an interesting point about the need to focus and direct anger. Revolutionary leaders from L’Ouverture to Gandhi to Garvey to Malcolm to King to Mandela knew that anger was an essential ingredient in any major movement against white oppression. The masses had to be roused from acquiescence to outrage. And a necessary part of that transformation was for them to get to a point where they were willing to lay down their lives for the cause.

King was acutely aware of his mortality, about how death was a lurking presence, a scowling beast always waiting around the next corner, rising up in the crowd at the next rally. But once he had brought enough people along with him in that state of expectation, once he was followed by an army of the outraged, equally willing to hand their lives over for a change in the condition of their people, they became an unstoppable force.

The shocking deaths of Black men over the last couple of years at the hands of whites, from Trayvon and Jordan to Garner and Brown, has roused in many African-Americans a new resolve to put it all on the line. What is my life worth if I am going to stand by and let my people, my sons and his friends, my nephews and nieces, become victims to overzealous policing?

We have heard it said over and over during the years, by leaders from Frederick Douglass to Malcolm X, that power concedes nothing without a demand. The corollary for the modern age should be that we must sacrifice comfort for true freedom. Practicing twitter activism isn’t enough. The demands must be made in person, in large numbers, with bodies conducting marches and “die-ins” in America’s offices and corridors of power.

If King were amongst us, he would be wary of any impulse to join demonstrations because your peers say it’s cool. That’s not going to get the job done. He would say our willingness to give up at least our creature comforts, if not our lives, needs to be made obvious and frighteningly apparent to the elites watching from the sidelines.

In King’s day he could depend on dense, bullheaded racist cops to over-react and put the images of beatings on the evening news to rouse a nation. We are (perhaps?) less likely to get such images now. That means we have to scream a bit louder in the streets—but we also have to smartly make demands in other arenas of our lives as well.

We have to call attention to the housing discrimination that circumscribes so much of our employment and educational opportunities, forcing us to live in communities where environmental problems eventually send us to early deaths.

We have to continue to fight the inequities in a criminal justice system that has used us as a white employment and profit center.

We have to fight and demand on many fronts, all at the same time, to truly make a dent.

But if he were here, King would tell us that we are capable of all these things, and so much more.