We are currently living in an age where poverty and disease are big business. In a world where race and class produce and reproduce ways of interacting. This process has found ways to attach itself to our very construction of individual and group realities, therefore entrenching conscious and unconscious acts of racism as being natural and universal occurrences.

We live in a world where racial diversity is misunderstood as ideological diversity, a constructed reality where the ascription of power is imposed on old ideas of identity and reincorporated in new forms of marginalization. This holds true, despite any claim of post-this or-that made by mainstream media, thinkers, or pundits.

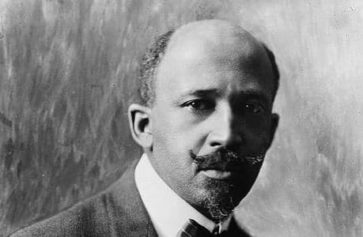

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in Souls of Black Folk in 1903 that: “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line,—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.”

Today, in the 21st Century, we are still confronted with this color line, which is exacerbated by a symbiotic relationship with the drive to secure material wealth at rates that often rival the height of the age of imperialism, where the total control of Africa as well as other resource-rich lands were/are the dominant behavioral expressions in geopolitics. Prophetically, in his later writings, as Du Bois delivers, expands or situates his conceptualization of the color line into being intimately linked with class formations.

Often ignored in the sympathetic democratic rhetoric of liberals are the racialized consequences of massive poverty and cultural displacement, integral to the globalizing project of democratization (a euphemism for the unbridled proliferation of capitalism).

In our experiences, powerful forces seek to reconfigure how race is lived on a daily basis. As old forms of accumulation by dispossession emerge and have increasingly impoverished much of the world’s population, it has equally created new forms of political, economic, and social stratification.

Within this environment, the meaning of race is constantly reconfiguring itself as various forms of exclusion built upon the consequences of enslavement, colonialism, and imperialism are perpetuated and refined.

While capitalism seeks to incorporate elements of racialized populations into its neo-liberal globalizing project, the old and rigid polarizing discourse built during direct imperial and colonial historical epochs become useless to the evolutionary needs of capital. Accordingly, there must be novel ways of managing the idea of race to maintain the legitimacy of the global racial and economic caste system.

This game is played out in the implementation of policies labeled “colorblind” or “race neutral,” or in something I called the post everything-we-do-not-want-to-really-deal-with era, aka post-race, post-colonial, post-history.

The implementation of such social constructions is more often than not simply the repackaging of white supremacy by denying the cultural-ideological class character of race.

So how do we understand this? How do we make sense of this current order? Why does it seem that marginalization based on now proven illogical and irrational conceptualizations of natural differences—which we term race—are salient?

In the U.S., race has been reconfigured and restructured. With the elimination of state-sanctioned racial segregation in the latter part of the 20th century, an ideology of colorblindness, which is a central theme to the myth of a racial democracy, has been promoted around the globe.

I argue, along with others, that the ideology of colorblindness is a smoke screen for a more dangerous and disturbing mission; more than to simply make race neutral. Within this frame of reference, all colors of value become white. Neutral—in this scenario functions as a euphemism for the construct—white. Hidden under the progressive idea that race is simply a social construct, is an insistence that race will not matter even in circumstances where racial inequities prevail, that is, colorblindness becomes racial blindness.

Taken further, this blindness masks the overt ideological and cultural imperatives of the myth of white superiority. Those who consider themselves liberals—and in many ways, some progressives—defend this colorblind ideology, while selectively blinding themselves to the real implications of a highly racialized and class-oriented society. Race is used to convey a model of the world as being divided into exclusive groups of people that are naturally ranked vis-à-vis one another.

What this suggests, then, is that dominance is a key component to the use of race. The forceful subjugation of other groups is a characteristic of those that are most exclusive in their conception of the kinship bond. It can then be argued that people who have a very narrow conception of kinship have a tendency to be more warlike and are extremely determined to dictate the construction and practice of social, political, and economic interactions.

This is done so that the history of successful social interaction not only breeds what can be called the dominant race, but the dominant race becomes the political race. Being so, these politically powerful people then seek to export particular social structures and forms of consciousness, within a particular worldview on others. Those who are considered to be lacking in this sense will not only be lacking in the capacities for this kind of racial or political dominance, but will come under the more forceful control of the so-called political or dominant groups.

What this means is that people who have not been successful in acquiring dominance, the people who have not been able to force their group identity upon another people, will be called inferior people. They are called “backward people,” not the norm, even though it may be historical fact that these so-called “backward people” have contributed more to the society to which they are part—then the so-called “dominant people” who hold social, economic, and political power within that society.

Within this social organization, the ruling elite will be the people who invariably dominate the group—this group will not only dominate the group practically, but seek to control the actual class distinctions that may prevail within the group, structuring almost all of the subordinate status of race from their will and their traditions.

To be continued….

James Pope, Ph.D., researches and maps the traditions and continuities of Africana thought and behavior as it relates to human rights, social movements, resistance to race as a cultural-ideological class construct, and critical consciousness formation. Currently, he is completing a book manuscript that explores the impact of race on the critical human rights consciousness of African-Americans.

Executive producer and co-creator of AfricaNow!: http://transafrica.org/africa-now/