There was joy in the Crimean capital of Simferopol yesterday, according to published reports, as Crimeans rejoiced in the opportunity to show the world that their emotional connection has always been with Russia—particularly older citizens who remember what it was like to be a part of the Soviet Union before the dissolution in 1991. Crimea had been a part of Russia since the 1700s.

“We were not asked when Crimea was combined with Ukraine. Now they are asking us,” Svetlana Fedotova, a small-business owner, told the New York Times as she arrived to vote in Simferopol with her daughter, Yekaterina, and 9-month-old granddaughter Yelizaveta. “We’re Russian and we want to live in Russia.”

By the thousands, crowds chanted “Russia! Russia!” in Simferopol’s Lenin Square, pumping their fists in the air in celebration, according to the Times’ David M. Herszenhorn.

“Our people must be united in Russia,” Yelena Parkholenko, 27, a manicurist with violet hair, said after her vote in Simferopol.

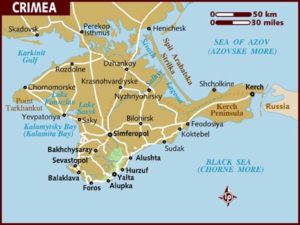

But the logistics of the matter might prove difficult for Putin and the Crimeans. Because of its geographic location, the peninsula of Crimea is connected to Ukraine to the north and separated from Russia to the east by a small body of water, the Strait of Kerch. A bridge connecting Russia to Crimea across the strait would take years to build—and until then, Crimea is dependent on Ukraine for essentials like water, electricity and natural gas.

But Sergei Aksyonov, the pro-Russian prime minister of Crimea, has reassured the residents of Crimea that contingency plans are in place to make sure his people get what they need.

“There are absolutely no grounds for switching the power off,” Aksyonov said at a news conference last week. “The bills are being paid in full and in compliance with the legislation of Ukraine. Such outages are possible only if it’s done of nuisance to play a nasty trick on Crimeans.”

Putin, who still has not clearly indicated what steps he will now take with Crimea, has been forced by the referendum to show his hand. Among his options are to move ahead and absorb Crimea, which would be a complex and costly venture given the peninsula’s geographic isolation, or to leave the Crimeans out in the cold, vulnerable to action by Ukraine, after they so overwhelmingly showed their confidence in his leadership.

The U.S. and the European Union, adamantly opposed to Crimea becoming a part of Russia, must also decide what hands they have to play to influence Putin. President Obama spoke with Putin by telephone on Sunday, but it was clear there was no progress.

“President Obama emphasized that the Crimean ‘referendum,’ which violates the Ukrainian constitution and occurred under the duress of Russian military intervention, would not be recognized by the United States and the international community,” the White House said in its statement. In addition, the president warned of “additional costs” to be imposed on Russia and urged Putin to take “a clear path for resolving this crisis diplomatically.”

After the passing of the referendum, the Crimean parliament today declared its independence from Ukraine and formally asked Russia to annex it.

The U.S. and the EU both responded by imposing sanctions on prominent Russian officials on Monday.

Obama signed an executive order freezing the assets and banning visas for a number of Russians who were seen as responsible for the seizing of Crimea. The White House threatened to go after more officials if Russia did not back down.

“We have fashioned these sanctions to impose costs on named individuals who wield influence in the Russian government and those responsible for the deteriorating situation in Ukraine,” the White House said in a statement. “We stand ready to use these authorities in a direct and targeted fashion as events warrant.”

According to the Times, the White House targeted a list that includes Vladislav Surkov, one of Putin’s most influential advisers, Sergei Glazyev, an economist who has been advising Putin on Ukraine, Valentina Matviyenko, chairman of the Federation Council, the upper house of parliament, and Dmitry Rogozin, a deputy prime minister.

Conspicuously absent from the list was Putin himself.

The foreign ministers from the 28-nation EU also announced that they had imposed travel bans and asset freezes on 21 people they blamed for the moves to wrest Crimea from Ukrainian control.

But as opposed to the U.S., the EU ministers refrained from publicly identifying the names on the list.

The sanctions are clearly the first stage in an escalating campaign of sanctions, but observers don’t expect them to have much impact on Putin, who called the referendum “fully consistent with international law and the U.N. Charter” and cited what he called the famous Kosovo precedent, referring to the province that amid atrocities on Kosovar Albanians broke away from Serbia with Western help and eventually declared independence.

Putin’s spokesman, Dmitri S. Peskov, said the sanctions would have no effect on Russia’s policies.

Economic sanctions against Russia itself are the obvious next steps. But that won’t come without pain on both sides, particularly in the EU — Russia is the EU’s third largest trading partner.

While the Russian economy is vulnerable, with the value of the ruble falling, 30 percent of the EU’s natural gas comes from Russia.

But Polish Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski expressed confidence that damage would be minimized, saying, “I do not believe Russia can use it (energy) to put us under pressure. Moscow needs our money.”

Germany is especially vulnerable to Russian sanctions, as more than 6,000 German companies trade with Russia, according to the BBC. One poll showed that two-thirds of the German people opposed sanctions.

There are many European experts now regretting the decision by the EU to draft an association agreement with the Ukraine, which is the move that many feel triggered the current crisis.