In less than four decades, the organization was able to support and sustain various struggles for political independence on the African continent. These struggles were often violent like the national liberation movements in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and South Africa, among others.

The leaders of the OAU, despite their serious ideological differences on account of the cold war, closed ranks and negotiated the political independence of countries in the continent. In fact, the two existing world powers ( the U.S. and Soviet Union) often supported different liberation movements within a country during the fight for independence.

It is important to give credit to the earlier leaders of the organization such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Gamel Nasser of Egypt, Ben Bella of Algeria, Modibo Keita of Mali, Patrice Lumumba of the Congo, Sekou Toure of Guinea, Haile Salassie of Ethiopia, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and others who sacrificed their personal comfort, territorial space, and resources to ensure political independence for countries in the African continent.

During the independence celebration of Ghana, President Nkrumah asserted that the independence of Ghana was incomplete except it was linked to the total liberation of Africa. What the African Union is trying to pursue, like the African Economic Union, owes its root to the analysis of Nkrumah who, indeed, was far ahead of his time. The African Liberation Committee of the then-OAU located in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, was very active. Tanzania gave a large area of its country to the African National Congress– the movement that fought for the liberation of South Africa. During the struggle for the emancipation of that country, Nigeria was the only frontline state outside the frontline countries and it committed much of its resources to the political independence of not just South Africa but to all the other countries struggling for independence.

After countries in Africa gained political independence, economic freedom became a serious challenge. African countries were unable to break away from the economic aprons of their former colonial masters. These imperial powers, like Britain, France, Spain, and Portugal, had integrated their colonies into the world capitalist system. Therefore, in essence, though the African countries were politically independent, their economies remained neo-colonial.

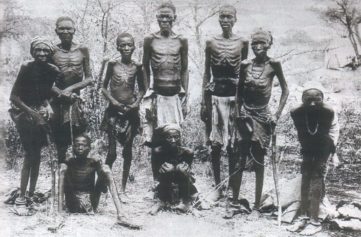

African countries exported raw materials, natural resources and unskilled labor to the economies of their former oppressors. Within the African countries, the new leadership and elite class became more interested in primitive capitalist accumulation than in addressing the fundamental problems of underdevelopment, hopelessness and poverty. This is not to suggest that there were no marginal successes such as the emergence of an educated class of Africans, relative infrastructural development, etc.

For the most part, the economies of Africa, particularly sub-Sahara Africa, SSA, were driven by the ups and downs of prices of commodity exports. No economy in SSA is industrialized, thus most of the existing companies were either assembly plants, packaging or bottling. In addition, they were branches of transnational companies and so the situation remains the same today.

Apart from bad economic and political governance, the austerity measures and later the structural adjustment programs in most African countries in the late 1970s and 1980s could be traced to sharp drops in the prices of commodity exports.

When variables like primitive accumulations, corruption and looting of the treasuries are added to the equation of Africa’s development, it is not surprising that poverty has increased, inequality has widened and most, if not all of the countries, thus remain underdeveloped. In Botswana and Ghana, two countries seen as success stories by the Breton Woods Institutions, poverty and widened income inequality still persist.

Freeing the economies of Africa from dependence on commodity exports remains a serious challenge. This present crop of African leaders emerging from democratic struggles have attempted to better manage their economies in a macroeconomic sense. For example, in the recent global economic crisis, African economies grew positively and were less hit by the global financial crisis. During the crisis, the performance of macroeconomic fundamentals such as growth, inflation and unemployment were relatively satisfactory. Of course, most of the African economies do not have sophisticated financial systems, hence their partial insulation from the global crisis.

All recent forecasts show that economies of Africa are experiencing macroeconomic stability, reflecting moderate inflation and robust growth. Ethiopia has a growth rate of 7.2 per cent, Nigeria 6.5 per cent with single digit inflation, and South Africa about 5 per cent.

Sub-Sahara Africa was projected to grow by about 5.2 per cent in 2013 and 5.8 per cent in 2014. SSA economies are now the destination for new investors, especially in infrastructure. A few years ago, the World Bank published: Can Africa Claim the 21st Century? Several scholars and those interested in Africa’s development have argued that Africa would be the next continent to leapfrog into sustained development.

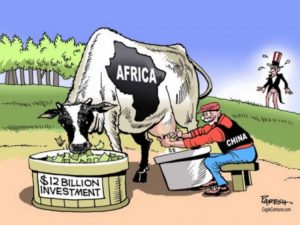

The austerity in the economies of Europe has resulted in the search for new markets and Africa is the continent to explore and exploit. Even the Portuguese who destroyed the economies of their former colonies, have returned to Angola, Mozambique and others to invest and search for employment. The new entrants from Asia, particularly China, have massive investments in Africa. Are they properly engaged by our leaders and policymakers? African leaders, policy-makers and technocrats must negotiate with these new investors bearing in mind that despite the macroeconomic stability and satisfactory growth, the African economy is suffering from very high rate of unemployment (25 percent),especially among the youths, extreme poverty and widening inequality – unprecedented in the last 20 years.

These “new” investors are not charity organizations, but are interested in not just earning high returns for their investments but also in growing their austerity-stricken economies in Europe. Today’s African leaders must work aggressively towards economic emancipation so that 25 years from today, Africa would be a developed, modern and knowledge-based continent with poverty at its barest minimum.

By Akpan- H. Ekpo a Professor of Economics, is Director-General, West African Institute for Financial and Economic Management

Source: tellng.com