On Jan. 7, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit heard an oral argument in the National Association of Manufacturers v. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission case about the legal requirements that companies investigate and disclose whether their products contain conflict minerals that are necessary to the functionality or production of the product.

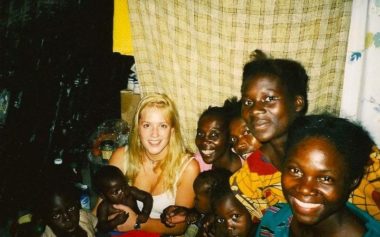

Four key metals used in popular consumer products such as cellphones, computers and gaming consoles — tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold — are defined by federal law as conflict minerals. Mined in war-torn countries in Africa, especially the mineral-rich Democratic Republic of Congo and its neighbors, their sale has funded warring paramilitary factions. Whatever the outcome of the case, the continuing legal battle is changing the way big electronics manufacturers’ source raw materials for their products, thanks to increased public scrutiny and growing consumer awareness.

For years, the activist group Enough Project and U.K.-based Business & Human Rights Resource Centre have tried to educate consumers in the West about the human-rights abuses in the countries where these minerals come from. Socially responsible investors (SRI) such as Calvert and Boston Common Asset Management have also pushed manufacturers to take responsibility for their supply chains.

In 2010, SRIs and human-rights advocates scored a hard-fought victory by getting a provision on conflict minerals included in the omnibus financial-services and securities-law reform package known as the Dodd-Frank Act. Section 1502 of the act requires public companies to investigate their supply chains and disclose annually where the minerals used in their products originate and to certify whether they are conflict-free.” The investigation into their supply chains must include an independent private-sector audit. The law mandates these firms to notify both the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the public via their Web pages.

The SEC, the primary regulator of publicly traded companies, was tasked with promulgating administrative rules on how to implement conflict-mineral disclosure. Shortly after the rule was finalized, in October 2012, the nation’s biggest trade associations, including the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), the Business Roundtable and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, filed a federal lawsuit to stop the disclosure rules, which are scheduled to take effect May 31, 2014.

When the SEC won the NAM v. SEC case, industry groups appealed to the powerful D.C. Circuit. Amnesty International has joined the case to help the SEC defend the conflict-minerals rules. London-based nonprofit Global Witness, the Wall Street watchdog Better Markets and several U.S. lawmakers have filed amicus briefs in support of the SEC. Several industry groups — including the American Petroleum Institute, the Can Manufacturers Institute, the National Retail Federation and the Retail Litigation Center — lodged briefs opposing the rules.

Last week’s oral argument before the D.C. Circuit’s three-judge panel focused on 1) the SEC’s decision to leave out an exception for products that contain only trace amounts of conflict minerals, 2) the SEC’s alteration of the original language on conflict minerals’ origins and 3) whether the reporting obligations imposed by the disclosure rule violates the First Amendment. While predicting the outcome of a pending legal case on the basis of oral arguments is perilous, the judges seemed receptive to the argument that requiring firms to tell the public whether their products have conflict minerals (or not) was compelled speech.

The compelled-speech doctrine is an application of the First Amendment, and in a nutshell, it means that the government cannot force individuals to endorse statements they don’t agree with. In the famous 1977 “Live free or die” case, a New Hampshire man won the right to cover up his state’s motto on his license plate because the state could not constitutionally compel him to have its speech on his car.

But there are less benign applications of this First Amendment right, especially when applied to corporations. For example, a 2012 ruling on compelled speech by the D.C. Circuit allowed the tobacco industry to block the Food and Drug Administration’s regulation that would have placed graphic warnings on cigarette packs. The D.C. Circuit seems poised to give a similar pass to companies with conflict minerals in their supply chains.

That is the potential bad news. The good news there is now a greater public awareness about conflict minerals. Among other efforts, the Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers and “House of Cards” actor Robin Wright have been campaigning to bring attention to the conflict-mineral issue.

Meanwhile, companies are trying to clean up their supply chains. The reasons for this change differ from company to company. While some are simply trying to avoid bad publicity, others endorse social and environmental responsibility. Managing a conflict-free supply chain is no simple task. It requires companies to trace their raw materials to smelters and then confirm where the smelters sourced the minerals.

While efforts to trace conflict minerals to their sources are encouraging, enormous challenges remain. “We require all of our suppliers to certify in writing that they use conflict few (sic) materials,” the late Steve Jobs said in 2010 when asked about Apple’s use of conflict minerals. “But honestly, there is no way for them to be sure. Until someone invents a way to chemically trace minerals from the source mine, it’s a very difficult problem.”

There are tools to help companies comply. The Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition, along with the Global e-Sustainability Initiative, has developed a smelter-validation program, which examines the procurement activities of each smelter. They maintain an online list of conflict-free smelters. And the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development has issued guidelines for conducting supply-chain investigations into minerals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas.

Read the full story at america.aljazeera.com