After 10 weeks of testimony from dozens of witnesses in the New York City stop-and-frisk trial, the case is now in the hands of U.S. District Court Judge Shira Scheindlin, who must decide whether the tactic as used by the NYPD over the past decade unlawfully violates the rights of residents.

Since blacks and Latinos make up just over a little more than 50 percent of the city population but 85 percent of the people stopped by police, the plaintiffs accuse the police of “using race as a proxy for crime,” in the words of Darius Charney, one of the lawyers for the plaintiffs.

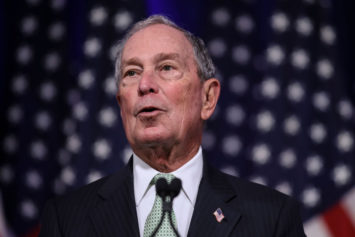

Stop-and-frisk has also become a flashpoint in the upcoming mayoral race for the successor to Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who has been outspoken in his support of the tactic, upsetting black and Latino residents, while the Democratic candidates have all opposed it.

Scheindlin, who is seen by many as an enemy of the police department because she has ruled against it so often in the past, is expected to issue her decision on the case within two months.

She has already ruled in a separate case in January that the stop-and-frisk tactic used by police in the Bronx to patrol the property of private landlords — at the invitation of the landlords — was a violation of the constitutional rights of Bronx residents.

Because of the January ruling and Scheindlin’s history, city lawyers clearly expect they will be on the losing end of this stop-and-frisk challenge.

Of the 5 million stops made in the past decade, only about 10 percent resulted in arrest or summonses, with a weapon recovered just a fraction of the time.

“They laid siege to black and Latino neighborhoods over the last eight years … making people of color afraid to leave their homes,” Gretchen Hoff Varner, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, said Monday during summations.

The officers who testified spoke of dangerous crime patterns, crime suspect descriptions and observations that they made while on patrol that led them to use the tactic. City attorney Heidi Grossman said their testimony demonstrated that race was not the basis for the stops, meaning the officers were not profiling.

“They failed to show a single constitutional violation, much less a widespread pattern or practice,” she said of the plaintiffs, adding there was “no indication of racial motivation whatsoever.”

“The alleged complaints of racial profiling are more fiction than reality,” Grossman said. “It is not the NYPD’s policy to target black and Hispanic youth, to instill fear in them so they feel they can be stopped at any time.”

During her questioning of attorneys, Scheindlin raised the possibility of ordering the NYPD to make officers wear cameras to help dispel discrepancies between encounters.

Many supporters of stop-and-frisk, such as Bloomberg, have claimed that the tactic is responsible for the unprecedented drop in crime in the city in recent years. But critics point out that crime continues to drop even as police have drastically reduced the use of stop-and-frisk. Scheindlin has indicated that she isn’t at all concerned with the policy’s effectiveness.

“I’ve repeatedly said that one issue that is not present here is the effectiveness of this policy, because that’s not for this court,” Scheindlin said during the trial, according to a story in The New Yorker. “This court is only here to judge the constitutionality…We could stop giving Miranda warnings. That would probably be exciting for reducing crimes. But we don’t allow that. So there are a number of things that might reduce crime, but they’re unconstitutional. This court is only concerned with the Constitution, not with the effectiveness of the policy.”