Fifty years ago this month, Martin Luther King Jr. drafted a letter from a cramped cell in Birmingham, Alabama. King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Jonathan Rieder says in his new book, “Gospel of Freedom,” reveals a more complex King, tough and tender, in equal measure.

Rieder’s narrative reflects a major shift in the way many historians now understand the African-American freedom struggle. The new scholarship challenges the division of black activism into integrationism and separatism, blurring the previously sharp lines between non-violence and violence, civil rights and black power.

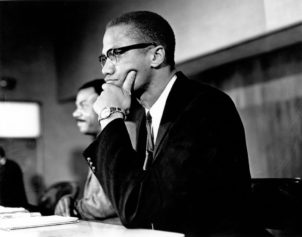

Rieder aims to replace the “sunny view of King” as a quixotic champion of the American dream and interracial brotherhood with a fiercer and more uncompromising King, a man who consistently preached a doctrine of black self-sufficiency. Martin, in other words, wasn’t that far from Malcolm.

While Rieder succeeds in showing us a more multifaceted King, he neglects the long history of African-American rhetorical dissent that shaped King’s message.

King went to Birmingham in early 1963 to help lead a campaign to integrate the downtown water fountains, lunch counters, and restrooms. Birmingham, or “Bombingham” as it was known to many of its black residents, was widely recognized as one of the South’s most segregated cities, a “notorious bastion of racist terror.” The pugnacious Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor oversaw the city with a police force packed with Klansmen and their sympathizers.

Attempting to re-energize a flagging boycott campaign, King successfully courted arrest on Good Friday by violating a court injunction against marches. Instead of placing King in a cell with his colleagues, Connor put him in solitary confinement, prompting King to remark, “He’s a smart old cracker.”

Over the weekend, King’s attorney passed him a copy of the Birmingham News, which featured an open letter signed by eight of Alabama’s leading white clergymen under the heading, “A Call for Unity.” Branding King an outsider who favored “extreme measures,” the eight “moderate” clergymen derided the campaign as “unwise and untimely.”

The letter jolted an otherwise despondent King, and he began to craft a response by writing in the margins of the paper itself. When the margins filled up, he wrote on the coarse prison-grade toilet paper…

Read More: newrepublic.com