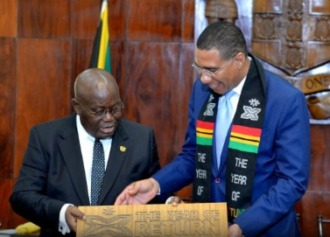

ON THE eve of Lent, Jamaica’s prime minister, Portia Simpson Miller, placed holders of government local-currency bonds on an austerity diet, asking them to accept a lower interest rate. Her finance minister followed up with unpopular emergency tax increases. In return, on Feb. 15th the International Monetary Fund announced a preliminary agreement for a $750 million loan. The Lenten diet is set to continue: approval of the credit by the IMF board will require prior approval of more tax increases and a public-sector pay freeze.

Simpson Miller has little choice. Jamaica suffers from low growth, declining productivity and a heavy debt burden (see chart). Its firms have lost competitiveness. But the island has a fraught history with the IMF, stretching back to the 1970s.

This month’s events were a repeat of those of three years ago, when a bond swap that lowered interest payments also marked the start of an IMF program. Bruce Golding, Simpson Miller’s predecessor, similarly agreed to reform taxes, the financial system and the public sector. After a resolute start, the program went off track. Public-sector pay rose by more than the target. With the economy stagnant and fierce political disputes over gang crime, Golding stepped down and his party then lost office in a December 2011 election.

Jamaica should do better than this. The island has plenty of well-educated, English-speaking people. It has great beaches, a near-perfect climate for farming, useful deposits of bauxite and a port that is just a short hop from both Florida and the Panama Canal.

But Jamaica lacks energy supplies. It spends more on oil imports than it earns from tourism. Households and businesses complain that electricity is expensive. For a decade, there has been talk of alternative fuels, such as liquefied natural gas or “clean” coal. Successive proposals have been blocked, some amid accusations of incompetence or mismanagement. Even if a program is approved this year, cheaper fuel remains at least five years off.

Violent crime wrecks lives, and may deter tourism. Businesses struggle with security costs. In an opinion poll in 2010, respondents ranked corruption ahead of crime and violence as “the most negative thing about Jamaica.”

Greg Christie, a lawyer and former businessman, last November ended a seven-year term as contractor-general, an independent official with power to look over all government contracts. In 2011 he said that of 40 cases referred in the previous three years to the director of public prosecutions, none had been pursued in court. Only one has since been successfully prosecuted.

Read the rest of this story on the Economist