What is Black? Race. Culture. Consciousness. History. Heritage.

A shade darker than brown? The opposite of White?

Who is Black? In America, being Black has meant having African ancestry.

But not everyone fits neatly into a prototypical model of “Blackness.”

Scholar Yaba Blay explores the nuances of racial identity and the influences of skin color in a project called (1)ne Drop, named after a rule in the United States that once mandated that any person with “one drop of Negro blood” was Black. Based on assumptions of White purity, it reflects a history of slavery and Jim Crow segregation.

In its colloquial definition, the rule meant that a person with a Black relative from five generations ago was also considered Black.

One drop was codified in the 1920 Census and became pervasive as courts ruled on it as a principle of law. It was not deemed unconstitutional until 1967.

Blay, a dark-skinned daughter of Ghanian immigrants, had always been able to clearly communicate her racial identity. But she was intrigued by those whose identity was not always apparent. Her project focuses on a diverse group of people — many of whom are mixed race – who claim Blackness as their identity.

That identity is expanding in America every day. Blay’s intent was to spark dialogue and see the idea of being Black through a whole new lens.

“What’s interesting is that for so long, the need to define Blackness has originated from people who were not themselves Black, and their need to define it stemmed from their need to control it,” says Blay.

Blackness, she says, isn’t so easily defined by words. What is Blackness for one person may not necessarily be that for another.

“And that’s fine,” Blay says. “Personally, my Blackness is reflective of my ancestry, my culture and my inheritance.”

“Black,” in reference to people and identity, she says, is worthy of capitalization. Otherwise, black is just another color in the box of crayons.

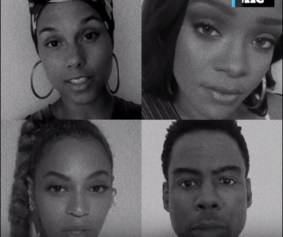

CNN interviewed some of the people who participated in Blay’s project to find out how they view themselves. What follows are their insights into race and identity.

Black and White

California author Kathleen Cross, 50, remembers taking a public bus ride with her father when she was 8. Her father was noticeably uncomfortable that Black kids in the back were acting rowdy. He muttered under his breath: “Making us look bad.”

She understood her father was ashamed of those Black kids, that he fancied himself not one of them.

“My father was escaping Blackness,” she says. “He didn’t like for me to have dark-skinned friends. He never said it. But I know.”

She asked him once if she had ancestors from Africa. He got quiet. Then, he said: “Maybe, Northern Africa.”

“He wasn’t proud of being Black,” she says.

Cross’ Black father and her white mother never married. Fair-skinned, blue-eyed Cross was raised in a diverse community.

Later, she found herself in situations where she felt shunned by Black people. Even light-skinned Black people thought she was White.

“Those who relate to the term ‘Black’ as a descriptor of color are unlikely to accept me as Black,” she says. “If they relate to the term ‘Black’ as a descriptor of culture, history and ancestry, they have no difficulty seeing me as Black.”

At one time in her life, she wished she were darker – she might have even swallowed a pill to give her instant pigment if there were such a thing. She even wrote about being “trapped in the body of a White woman.” She didn’t want to “represent the oppressor.”

She no longer thinks that way.

Read the rest of this story on newpittsburghcourieronline.com