There should have been a major announcement in some posh setting, maybe even a boxing ring in Las Vegas, with confetti ready to fall from the rafters and luminaries in the audience. That’s how a champion like Evander Holyfield should go out – with the people he entertained celebrating an accomplished body of work in general, and the heart of the man as a fighter in particular.

Instead, there is no fanfare. Instead, most are saying, “Thank God. Finally.”

Holyfield is 50, having fought probably 13 years past when he should have quit. The courage that he showed in being a smaller man fighting as a heavyweight was not matched by the wisdom to sit down when it was time. Worse, when those around him even questioned if he should continue, he fired them.

For the past decade or more Holyfield, instead of existing as an exalted former champion, has been considered a misguided, delusional, punch-drunk ex-fighter desperate to compete when he was far beyond his prime. In his last 16 fights, mostly against boxers you’ve never heard of, Holyfield is 8-7-1 with a no contest. All of these came when he was 37 or older – a time when he should have gone back to school or spent his time fishing. Sad, that.

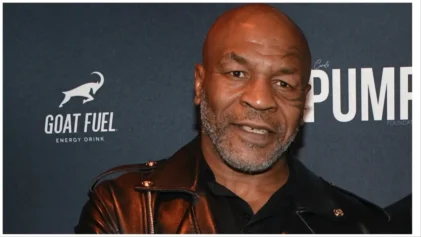

His career record of 44-10-2 (one no contest) is more sparkling than it suggests. When he elevated in class from cruiserweight to heavyweight, a young, swift and determined Holyfield defeated elite fighters such as Riddick Bowe, George Foreman, Larry Holmes, Ray Mercer, Michael Moorer and Michael Dokes. Of course, his two victories over Mike Tyson are what set him apart.

He pummeled Tyson in their first match, November 9, 1996, stopping him in the 11th round. A 24-1 underdog, Holyfield was atop the boxing world. They fought again in 1997, the infamous night Tyson resorted to biting off a portion of Holyfield’s ear because he could not compete with him.

Two years later, Holyfield lost a second time to Lennox Lewis in a fight in which he made the bigger, younger man fight until the final bell. In truth, that was Holyfield’s last hurrah.

He kept fighting, but accomplished little in the ring. He wanted to become a five-time heavyweight champion, but lost to someone named Nikolai Valuev, a 7-foot WBA champion from Russia. That was four years ago or nine years after his last commendable effort.

If you ask him today, 48 hours from when he turns 50, he would say he could still take one of the heavyweight belts. But he’s only fooling himself. Most places around the world would not even sanction a fight featuring Holyfield, although his body remains the envy of most men.

“The game’s been good to me and I hope I’ve been good to the game,” Holyfield said to Sports Illustrated. “I’m 50 years old (on Friday) and I’ve pretty much did everything that I wanted to do in boxing.”

He made more than $200 million in the sport. But he also has squandered most of it. He pays more than $500,000 a year in child support of his 11 children fathered among nine women. His lavish compound south of Atlanta that featured 17 bathrooms, three kitchens, a bowling alley, an Olympic-sized swimming pool, fishing ponds, etc., is his no more, devoured in foreclosure.

Much of his money also went to charity. He had a big heart. At his home each July 4th he would host hundreds of youths, providing food, games and entertainment, capped with a fireworks show when the sun dropped. He did not have to do it, but he did it because he felt it was his obligation to be a part of the community, a regular guy with extraordinary resources.

In the end, Evander Holyfield will be remembered as a boxer of utmost resolve and determination, The Real Deal. His personal life has not been so prolific. But he still has some living to do to determine the final arc of who he is as a man.

Curtis Bunn is a best-selling novelist and national award-winning sports journalist who has worked at The Washington Times, NY Newsday, The New York Daily News and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.