The face of boxing steps into prison today, an 87-day stint that defines the sport as much as it defines the times and the man.

That is not a compliment.

It, in fact, is an indictment—on boxing, the world we live in and Floyd Mayweather, Jr.

With an opportunity to represent himself and his sport in an upstanding fashion, Mayweather, instead, has failed boxing and himself. And there does not seem to be any outrage about it.

The best boxer in the world gets locked up on a domestic violence charge stemming from a September 2010 incident during which he pled guilty to pulling the hair and twisting the arm of the mother of three of his children. His sons, 10 and 8 at the time, were there when he also threatened and hit ex-girlfriend Josie Harris. The older boy ran out a back door to fetch a security guard in the gated community.

Sadly, boxing did nothing. No admonishment. No suspension. Nothing. So it’s no wonder that after all that, when he leaves the Clark County Detention Center in Las Vegas near the end of summer, he will have actually augmented his stature, his “street cred,” among many who deem it some warped mark of proud distinction to have been locked up.

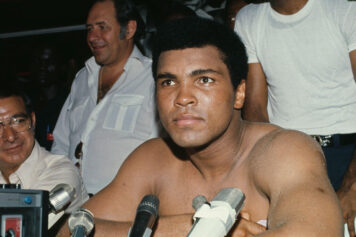

In one of his many and sometimes mindless rants about one thing or another during his remarkable boxing career, Mayweather, 35, has more than once invoked the name Muhammad Ali in relation to himself, a juxtaposition that is ludicrous, but interesting on this day in one way.

Ali once went to jail, too. And that’s where the comparisons should end, for Ali stood for something, whether you agreed with his position or not.

With the travesty of the Vietnam War getting even worse in 1967, Ali was called up for induction into the armed forces. Back then, men were drafted and had to serve or face jail time. Ali still refused because of religious beliefs. He also said: “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong. Ain’t no Vietcong ever called me (the N word).”

Ali’s refusal got him some jail time. Bigger was the national uproar it caused. His boxing license was cancelled by most states. He was stripped of his title, had his passport confiscated and did not fight for 2 ½ years. Instead of pouting, Ali lectured at colleges and Muslim gatherings around the nation, gaining support as antiwar sentiment increased. In June 1971, the Supreme Court reversed his conviction, ruling that he was entitled to an exemption as a conscientious objector.

That little history lesson should show how Ali and Mayweather are comparable only that they starred in the same sport. That’s it.

Here’s what Mayweather said on HBO: “I’m in the same shoes as Ali. They hate me when I’m at the top, but once my career is over, they’re going to miss me.”

On his domestic violence case, he said: “I took the plea. Sometimes they put us in a no-win situation. I had no choice, but I don’t worry about going to jail. Better men than me have been there. I’m pretty sure Martin Luther King’s been there, and Malcolm X. I have taken the good with the good so I’ll accept the bad with the bad.”

Sign of the times: Mayweather was sentenced on December 22, 2011, but judge Melissa Saragosa agreed at the last minute to let him remain free long enough to fight Miguel Cotto on May 5 in Las Vegas, which he did last month and earned more than $32 million—and injected millions more into Sargosa’s city’s economy.

Well, the money cannot help Mayweather now. He likely will not be able to train while in prison. For the first week or so, Mayweather will be segregated for his protection from the other 3,200 inmates. He’ll get one hour of exercise time a day outside his cell.

It could be worse for Mayweather. He could be a convicted rapist like Mike Tyson. Or maybe a miracle could happen: He could exit a new man of character and community ambition.

Don’t bet on it, though.

Curtis Bunn is a best-selling novelist and national award-winning sports journalist who has worked at The Washington Times, NY Newsday, The New York Daily News and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.