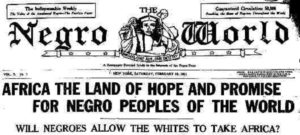

Universal Negro Improvement Association

“Go back to Africa!” It is the phrase du jour for racist whites, typically when used as part of a bitter, angry, expletive-laden rant against Black people. There are so many examples of the popularity of this insult these days.

A Beaufort, South Carolina teacher told a Black high school student to go back to the continent after he refused to stand for the Pledge of Allegiance. In Virginia, the Sons of Confederate Veterans told the African-American community to go back amid calls for the city council to remove the Confederate flag from a local museum. A Black student at Southern Illinois University was told the same thing when she was confronted by Donald Trump supporters in a residence hall. And at Trump rallies in Chicago and Cleveland, Trump supporters were heard yelling the phrase, along with other racial epithets.

“If you call yourself an African-American, go back to Africa. If you’re an African first, go back to Africa,” said a white man to a Black woman and #BlackLivesMatter supporter at a Trump rally in Cleveland this past March, as reported by MSNBC.

And recently, a Bank of America employee in Atlanta was fired for her racist Facebook rant.

“When a bigot says ‘Go back to Africa,’ he or she is simply being nasty and irrational,” Dr. Wilson Jeremiah Moses, Ferree Professor of American History at the Pennsylvania State University, told Atlanta Black Star. Moses is the author of Classical Black Nationalism: From the American Revolution to Marcus Garvey and Liberian Dreams: Records of an African Return 1853, among other works. “I am not wise enough to know to how one can best respond to nastiness and irrationality.”

To be sure, there is a nastiness to the phrase, particularly when accompanied by other insults, threats and acts of violence. For example, in October 2014, when a group of Black protesters outside a St. Louis Cardinals game sought to bring attention of the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, they were met with a crowd of virulent white racists. As Crooks & Liars reported, the white fans responded to the Black protesters by chanting “Let’s go Cardinals,” which changed to “Let’s go, Darren!” in honor of Officer Darren Wilson, who shot and killed Brown. While attempting to initiate acts of violence, the white fans told the protesters to go back to Africa and called them jobless, while one of the white men called a Black activist a “crackhead.”

“We’re the ones who gave all y’all the freedoms that you have!” shouted one white woman at the African-Americans, as a number of fans began chanting “Africa, Africa” – shorthand for the suggestion they go back to the motherland.

And part of the assumption among whites is that Black folks should be happy to be in America, which, through its kindness and generosity, has rendered African-Americans the most fortunate Black people around. There is a perverse, outlandish assertion that Black people — kidnapped at gunpoint and brought to these shores in the belly of a slave ship, and, if they survived, were raped, tortured and forced to toil in prison camp plantations — should leave if they cannot appreciate all that white people have done for them. Of course, the parties to whom Black people would presumably return the favor came to North America from Europe — unannounced and uninvited — and stole the land from the indigenous population right from under their feet. Yet, never are there any calls for whites to return to Europe.

This sentiment was best articulated by conservative commentator Pat Buchanan in 2008.

“First, America has been the best country on earth for black folks. It was here that 600,000 black people, brought from Africa in slave ships, grew into a community of 40 million, were introduced to Christian salvation, and reached the greatest levels of freedom and prosperity blacks have ever known,” Buchanan wrote on his website.

“Second, no people anywhere has done more to lift up blacks than white Americans. Untold trillions have been spent since the ’60s on welfare, food stamps, rent supplements, Section 8 housing, Pell grants, student loans, legal services, Medicaid, Earned Income Tax Credits and poverty programs designed to bring the African-American community into the mainstream,” he added. “Governments, businesses and colleges have engaged in discrimination against white folks — with affirmative action, contract set-asides and quotas — to advance black applicants over white applicants.”

“In the later editions of From Slavery to Freedom, John Hope Franklin gave a nuanced analysis of the multiple and complicated reasons why some whites and blacks supported African deportation before the Civil War,” said Dr. Moses.

In that book, Franklin wrote that as early as 1714, there was a proposal to send Blacks back to Africa. Whites believed the races could not live together in harmony, and free Black people could not adjust to life in America, and created a problem for maintaining the system of slavery.

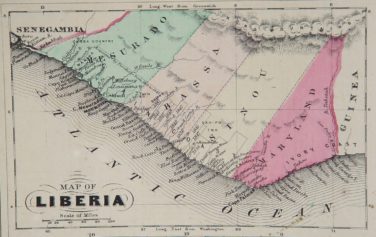

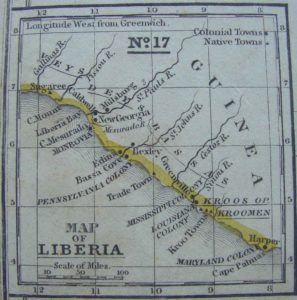

Map of Liberia, 1829

“There is no adequate history of the American Colonization Society,” said Moses of the organization which helped relocate thousands of freed Black people to what would become Liberia. “There is no satisfactory treatment of Henry Clay’s advocacy of African deportation or of Abraham Lincoln’s decreasing interest in African deportation, as he evolved from a Whig to a Republican. In my view, Lincoln was never convinced of the practicality of deportation, for reasons that Alexis de Tocqueville had articulated,” Moses offered. “I touched on my reasons for believing that Lincoln was not serious in my biography of Alexander Crummell (Oxford UP, 1989). As for Jefferson, I think he was absolutely insincere about African deportation. Jefferson was a complete phony, and like many populists he used democratic rhetoric to cover up aristocratic programs. He never joined the American Colonization Society and contrary to popular belief, never supported the abolition of slavery. Jefferson only called for ending the Atlantic slave trade except in order to inflate domestic slave prices,” he added.

“I would suggest that no discussion of the Back to Africa movements, either the white racist ones, or especially the Black ones (such as Garvey’s), is complete without considerable explanation of the nadir of race relations,” said James W. Loewen, the author of Lies My Teacher Told Me; Lies Across America; Sundown Towns; Teaching What Really Happened; and The Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader. During the nadir, which began during the end of Reconstruction and lasted through the early 20th century, was a time of white supremacy, Jim Crow segregation, racial terrorism and a loss of civil rights for Black people.

“Going back to Africa was hardly irrational, given how race relations grew worse and worse after 1890. That needs to be explained, lest Garvey, et al., come across as charlatans,” Loewen, who taught race relations at the University of Vermont, told Atlanta Black Star.

Meanwhile, many African-Americans today are crossing the Atlantic to live in Ghana, once a major starting point of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, and one of the first African nations to emerge from colonial rule. While millions crossed the Middle Passage by force via Ghana for a life of permanent enslavement in America — 40 percent never making it to the other side — some of their descendants are returning for a better, more comfortable life, business opportunities and to rediscover their roots.

Ghana has a Right of Abode program that grants permanent residency and dual citizenship to people of African descent. According to the African-American Association of Ghana, 3,000 African-Americans live in Ghana, most in the capital of Accra. So, some Black people are going back to Africa, but they are doing so on their own terms. And as the future becomes more difficult and more uncertain for people of African descent in the U.S., certainly more will consider the option.