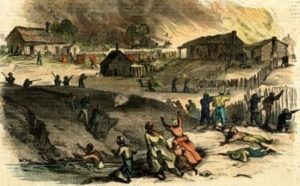

Memphis Massacre Painting. Public Domain

This week, the city of Memphis, Tennessee, commemorates the 150th anniversary of one truly horrific event in its history: The Memphis Massacre.

The post-Civil War South was a pressure cooker of racial angst, with disenchanted whites and newly freed Blacks forced to rebuild their lives in a shared space. In Memphis, tensions were extremely high between white city police and Black Union Army soldiers recently discharged by the U.S. government. On May 1, 1866, tensions exploded when an altercation between a Black soldier and the white policeman attempting to arrest him led to a deadly shootout. Historians estimate nearly 50 Black former soldiers rushed to his defense that afternoon. The aftermath was a three-day slaughter led by white mobs, which left 46 Blacks dead and 91 homes, four churches and eight schools in the Black community burned to the ground. No arrests were made.

The violent episode drew national attention and is credited with influencing Congress to pass the 14th Amendment, granting full citizenship to all formerly enslaved Black men.

Last November, Tennessee Judge Bernice B. Donald and local NAACP board member Phyllis Aluko led a group proposal to erect a state historical marker in acknowledgement of the little-known, yet significant event that arguably forever changed Reconstruction-era America.

“It’s important that those people, those victims of racial injustice, that their lives be remembered,” Donald said at the time. “It’s important to show that their deaths were not in vain. That their deaths led to significant changes in our country.

“History is neither pro nor con, but it’s always relevant. If we don’t understand significant events of the past, we won’t understand what is happening and why it’s happening today. It’s all connected.”

The group partnered with the Tennessee Historical Commission and the National Park Service to move forward with the project.

But talks hit a roadblock in February when commissioners became locked in a debate over the use of the words “race riot”on the marker. The Commission wanted to put “Race Riot” atop the sign, while groups leading the effort wanted “Massacre.” Due to decades of slanted media coverage, some argued the term “race riot” is too loaded and calls to mind images of Black people busting out store windows, “looting” and setting fire to police cars.

University of Memphis historian Beverly Bond told NPR the argument was more than a matter of semantics.

“Naming is very important. If your name is John and I insist on calling you Johnny, it’s really a power relationship,” Bond says. “Most people tend to think in a 20th-century frame of reference that [race riot] must be African-Americans who are rioting and destroying their community.”

Steven V. Ash, author of A Massacre in Memphis: The Race Riot That Shook The Nation One Year After The Civil War, said newspapers of the time called it a race riot due to an abundance of misinformation circulated by local whites.

“The rumor among the whites was that this was a full-scale Black uprising in South Memphis,” Ash told NPR, “and so white mobs began forming, marched into South Memphis and began indiscriminately shooting Black men, women and children.”

Massacre won out in the end. The sign reads: The 1866 Memphis Massacre

City leaders gathered in Memphis’ Army Park to unveil the historical marker on May 1.

Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland spoke a few words at the ceremony, The Commercial Appeal reports.

“Let us make no mistake. It was a massacre,” he said.

Aluko, the local attorney responsible for bringing the marker to fruition, was present for the Sunday service. Aluko authored the sign’s writing, which bears the names of known victims of those fateful three days.

“We can’t give them justice, but we can honor their lives and their sacrifice,” Aluko said. “May we always remember their sacrifice.”