The more researchers, reporters and officials examine such cities, the more aware they become of the deeply rooted issues that have left the cities’ residents trapped in poverty.

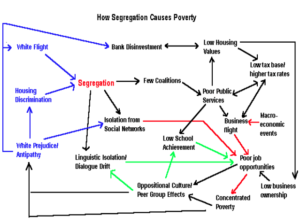

Perhaps one of the biggest issues is that of segregation.

The Equality Opportunity Project of Harvard University recently released two papers that unveiled the true ugliness of segregation and how it plagued the lives of its young victims.

According to the report, in a city like Baltimore, found to be the worst large city in the country for poor children when it comes to income mobility, a child’s future earnings can tumble by 0.7 percent every year they spend in that city.

Children who have been in the city since birth tend to total up an earnings penalty of roughly 14 percent, according to researchers Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren.

“Geography is not quite destiny,” The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson writes. “But neighborhoods can drastically shape the economic prospects of those who grow up there. One hour south on the I-95 of Baltimore is Fairfax, Virginia, one of the 10 best large counties for low-income children. Growing up in Fairfax for 18 years raises a typical low-income child’s household earnings by 11 percent by the time he’s in early adulthood. All else equal, the difference between growing up in Fairfax rather than Baltimore, these studies say, amounts to hundreds of thousands of dollars of lifetime earnings.”

Fairfax has a predominantly white population with less than 10 percent of its residents being Black.

That’s the ugly reality of segregation. It’s not just about being separated, but also the vast difference of opportunities that exist for those in a predominantly white community when compared to a predominantly Black community.

That fact is not new and it’s not surprising, and it doesn’t warrant a new chapter of discussions about segregation.

What does warrant the igniting of a new conversation is the one-dimensional approach to solving the problems caused by segregation.

Historically, the approach has been to simply plop more Black families in neighborhoods that provided better opportunities and economic stability — in other words, relocate them to predominantly white communities.

This move has historically been done through government voucher programs that give selected residents a set amount of time to find property in high-opportunity neighborhoods, but such programs still don’t provide a thorough solution.

Rather than taking an approach that asks “how to move Black families to better areas” it seems there needs to be more exploration of a plan that asks “how do we improve the neighborhoods that are currently trapped in poverty and have little access to good schools and are being plagued by crime.”

Many families have already planted their roots in some of these impoverished communities and find it emotionally taxing to leave such ties behind even if it’s in order to seek better opportunity elsewhere.

“When it came down to it, a lot of them had lived there for generations, and they wanted to go somewhere comfortable and familiar,” said Susan Popkin, a scholar at the Urban Institute that has studied where residents moved after receiving vouchers under housing mobility programs in Chicago. “Unless they had a connection, they weren’t interested in going any further.”

Not to mention that even better economic opportunities don’t always create better environments for Black youths.

This is not to detract from the fact that many of the families who were relocated as a part of such voucher programs did see an increase in certain opportunities.

Their students were excelling and they were able to quickly find better employment opportunities, but why did they have to move to a suburban area to find such opportunity? Why were they being asked to run away from their communities in order to have the decent lifestyle that one would think would be afforded to all Americans?

What about the families who can’t afford to simply pick up their lives and relocate to a new neighborhood?

“It needs to be a two-pronged approach,” University of Illinois professor Ruby Mendenhall told The Atlantic. “You can’t ignore what happens in these neighborhoods.”

Popkin added that access to quality housing needs to see a drastic increase in low-income communities and officials should find an obligation to create changes in such communities that have been plagued by years of discriminatory practices in housing that helped usher the communities to their demise.

Not to mention the approach of relocating families completely ignores the historical problem of “white flight,” in which white families tend to relocate in masses once families from low-income areas start moving into their neighborhoods.

So while the idea of integration through vouchers and other relocation methods may have nothing but good intentions, it is, nonetheless, a quick solution that isn’t likely to stand the test of time if there isn’t a drastic refocus on fixing communities like Baltimore and St. Louis rather than just helping people run away from them.