As a pre-teen Black boy, Anthony Harris was forced by local police to confess to the death of his 5-year-old neighbor 24 years ago. Now as a man, Harris is speaking out for the first time about the psychological and emotional trauma he bears from the wrongful conviction and coerced confession that led him to spend two years in prison.

Legal documents revealed Anthony Harris was 12 years old when his neighbor, a small blonde-haired blue-eyed white girl, was murdered in a New Philadelphia, Ohio, apartment complex in 1998. Harris, along with four other relatives of the girl, was identified as a suspect.

A new interview with ABC News anchor John Quiñones on the 20/20 special “Gone Before the Storm” shows a man still living in the shadow of the investigation.

Law enforcement, led by Captain Jeffrey Urban, locked in on Harris after learning “he had once pushed or struck Devan Duniver in the arm and threatened to kill her,” the boy’s appeal stated.

Police reported the boy was close to the place where the girl’s corpse was eventually found and one day after her disappearance, “before her body was found, Harris approached Urban and another officer and volunteered the statement that Devan was a ‘rude, nasty little girl who would eat in front of him.’ ”

That fragmented collection of evidence shifted the attention from family members of Devan to exclusively focus on the African-American child.

The captain, according to the filing, never followed up on leads about the girl’s mother, father, stepfather/ mother’s boyfriend and/or brother.

Those around Devan were a complicated mix of violent individuals but were removed as “persons of interest” in killing the little girl who had been brutally stabbed seven times in her neck.

Her mother, Lori Duniver, who discovered the child missing from their home, had “called a suicide hotline to report she felt depressed and was considering harming herself and her children.”

A man named Richard, Devan’s father, was described as “a violent alcoholic and who had recently complained about having to pay child support for Devan,” told authorities he would not help Lori find the child because he was too intoxicated to drive the community to search.

The boyfriend, Jaimie Redmond, a drug addict and felon, previously had “kidnapped Devan for three days and beaten her with a belt.”

Testimony from insiders shared that the child was deathly afraid of him. Redmond also was carrying a pack of children’s playing cards when police first detained him and the person who provided an alibi for him gave authorities a fake name and Social Security number as identification.

The last person of interest in Devan’s murder was her brother Dylan. While he was not a substance abuser like the other two males, nor suicidal like his mother, people said he was “violent,” noting he had stabbed a cat around the time of the child’s killing.

Urban was unmoved about his instinct about Harris and on July 15, 1998, had the boy’s mother, Cyndi Harris, bring in her son to undergo a voice-stress analysis test.

He told the mother it was similar to a lie detector test.

Instead, Millersburg, Ohio, police chief Tom Vaughn read the pre-teen his Miranda rights and began to “interrogate him about the murder” without the consent of the mother. Under the pressure of the officer, a young Harris cracked and confessed to the killing, even though “many aspects of Harris’s confession conflicted with the known facts of the murder.”

When Vaughn asked Harris to write his confession, he asked for his mother. After speaking to his mother, he recanted his story, his appeal stated. However, the courts permitted the confession. Harris would be convicted in a juvenile court and sentenced to almost 10 years in prison on March 17, 1999.

Quiñones asked Harris why he confessed, to which he answered that he just wanted to “go home.”

Similar to actions in the Central Park Five criminal case in 1989, Harris says the officers coerced him with the promise to let him free if he just told them what he wanted. “The investigator, he had basically told me that, ‘If you confess to this murder you can go home,’ ” Harris recalled.

“It’s like, ‘Okay. Well, I’m over here scared, so I want to go home.’ “

Harris ended up serving two years in an Ohio juvenile detention before his legal team filed an appeal and a judge decided to reverse the conviction on June 7, 2000.

While incarcerated, Harris talked to Quiñones at 13 years old, telling him, “I did not kill Devan.”

The Ohio Court of Appeals, according to court documents, freed him not because it believed he was innocent or reviewed new evidence, but “on the ground that the juvenile court had improperly denied a motion to suppress his confession, which was coerced in violation of his Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination.”

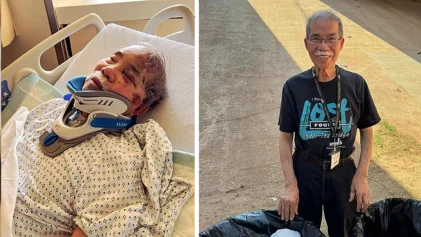

Twenty-two years later, Harris tells the veteran journalist, he is still marred by the offense, despite serving two tours (Iraq and Afghanistan) in the U. S. Marines.

However, service to his country could not mend the gaping hole in his heart left from the wrongful conviction and imprisonment especially since the case has never been solved and theoretically Devan’s murderer is still at large.

Quiñones showed Harris a picture of him when he was 13, in his first interview with him, and Harris broke into tears, saying, “It hurts.”

He said, “Pardon my tears. I have a little strong emotion. I look at myself and I can tell I was just stuck. I thought the world was just tearing me apart and I couldn’t escape it.”

“It hurts,” he continued. “I have some friends who have kids around Devan’s age. Sometimes I look at their daughters and it just hurts me a lot.”

When asked if he “would have ever harmed her,” he said, “Nah, I would have never done that to that girl.”

At 34, Harris now lives his life as a union ironworker.