An Oregon police sergeant is facing misconduct charges for his role in the wrongful arrest of a Black Man, but the victim and his attorneys say it is not enough.

Reports show Michael Fesser’s former boss plotted with police officials to retaliate against him for complaining about racial harassment at work.

According to reports, West Linn police officials launched a rogue investigation into Fesser in 2017. They illegally surveilled him and seized his cash and cellphone without a warrant and arrested him without probable cause, court records show.

“This case vividly illustrates a ready willingness on the part of the West Linn police to abuse the enormous power they have been given, and a casual, jocular, old-boy-style racism of the kind that we Oregonians tend to want to associate with the Deep South rather than our own institutions,” Fesser’s attorney Paul Buchanan said.

Eric Benson owned a towing company, where Fesser managed vehicle auctions. Benson used his relationship with the West Linn Police chief at the time to conspire to get Fesser arrested, even though Fesser had no connections to West Linn. Fesser worked and lived in Portland. Reports also show police officers falsely labeled Fesser a gang affiliate and recorded audio of him without a court order.

The case files included a trail of racist texts between Benson and former West Linn Police Sgt. Tony Reeves. Reeves was charged with first-degree official conduct on Feb. 25, five years to the day of Fesser’s false arrest.

Fesser has received more than $1 million as a result of discrimination lawsuits, but he and Buchanan are concerned that high-ranking West Linn police officials may have escaped prosecution.

“Those were the experienced officers in leadership roles who defined the culture in that police department,” Buchanan told reporters. “In my view, they bear much more responsibility for what happened here than Officer Reeves.”

Reeves, under the direction of former Police Chief Terry Timeus, was the lead detective in West Linn’s case against Fesser. Timeus and Fesser’s former employer, Benson, were fishing buddies.

Fesser told his boss of three years that other employees called him racist slurs. According to reports, one of Fesser’s coworkers asked him how he liked a Confederate flag that was fastened to a pickup parked in the tow company’s lot. Benson reportedly complained to the police chief that Fesser was stirring up problems in his company.

The Oregonian reported Timeus sent a text message to Benson on Feb. 21, 2017, saying his detective was finishing up a sex crimes case “and will have your case ready to go before Saturday … If I hear more, I’ll let you know.”

Court reports show West Linn officials instructed someone close to Benson to record Fesser at work on an audio app. Benson also watched him on the company’s video surveillance cameras and logged his moves through text messages to Reeves.

In one exchange, Benson sent Reeves a photo of his dog. Reeves texted, “Hope Fesser doesn’t get her in the lawsuit.” Benson texted back, “Hahaha. She is not a fan of that type of folk. She is a wl (West Linn) dog.”

In another exchange, Benson told Reeves that he regretted Fesser was not being arrested by another police agency because he had hoped to “make sure he was with some real racist boys.”

“Dreams can never come true, I guess,” Benson added.

Reeves later admitted to investigators that they did not find any evidence to support Fesser’s arrest. Reeves instructed another West Linn officer and five Portland Gang Enforcement officers to stop Fesser as he headed home from work that day.

“My game, my rules,” Reeves texted Benson. “It’s better that we arrest him before he makes the complaint (of race discrimination). Then it can’t be retaliation.”

Buchanan wrote in court records that Fesser only processed what really happened to him when he saw the text messages. The messages ultimately led to his acquittal.

“Only after he received the text messages did he understand that racism, cronyism and impropriety of the officer’s conduct and motivations,” Buchanan wrote. Fesser had deleted the text messages, but the attorney retrieved them later during the civil proceedings.

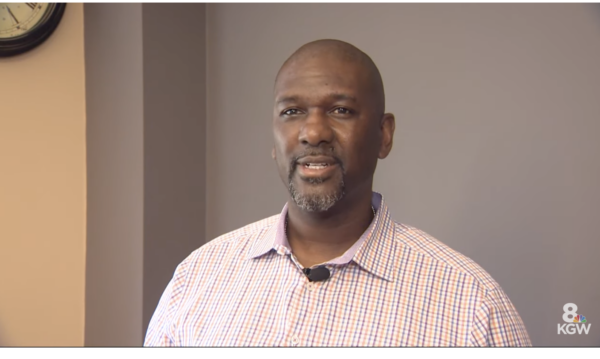

Fesser told reporters he was terrified during the encounter with the police. He was surprised to see West Linn police officers and knew he had not committed a crime.

The Oregonian reported police officers took Fesser to Portland’s East Precinct before taking his cash, cellphone, and a letter documenting the racial harassment from his vehicle. He was booked in a Portland jail on aggravated theft charges and released. Two days later, Fesser said police told him to retrieve his belongings, and they told him not to return to the towing company because he was fired.

“How do police fire me from my job?” Fesser told reporters he thought to himself.

Fesser learned later that the charges against him were dismissed, but they were refiled in November 2017, two months after he filed the discrimination lawsuit against Benson, his former boss.

The Oregon Department of Justice filed the misdemeanor charge against the former sergeant, Reeves, after the Clackamas County District Attorney’s office referred the case for an independent review, according to officials.

According to his deposition, Reeves was also disciplined for failing to properly document the seizure of Fesser’s cash after his arrest. The district attorney’s office concluded that Reeves withheld evidence and disclosed Fesser’s confidential attorney-client information to Benson.

The police chief said in a deposition that he heard Benson use a racist slur at least a “half a dozen” times. The chief also admitted to using a racist slur, but according to his deposition transcript, he could not recall using it when he served in the role or when referring to Fesser’s case.

In March 2018, Benson and his company agreed to pay Fesser $415,000 in damages, wages and attorney fees to settle his discrimination suit if he agreed not to bring any further legal action against the company or its agents.

That same month, Reeves was promoted to sergeant.

Fesser also filed a federal lawsuit against West Linn police. The department’s lawyers argued that West Linn officers were acting as “agents,” therefore the court should dismiss the case.

“This assertion is virtually an admission of misconduct,” Buchanan argued to the court. “Defendants were not seeking to engage in legitimate law enforcement. Rather, the officers were acting based on a striking and alarming personal malice, racism, and desire to protect a ‘good old boy’ from the West Linn community.”

Last February, West Linn police paid $600,000 to Fesser to settle the lawsuit. The department fired Reeves in June 2020. Fesser’s legal team also pushed for federal charges in the case, but the U.S. Attorney’s Office said they could not confirm the police department “willfully” violated his civil rights or federal corruption laws.

Timeus, the police chief, retired in October 2017 when he was faced with allegations that he drove drunk while off duty. He left with more than $123,000 in a separation agreement.

Timeus also had enlisted the help of Mike Stradley, a West Linn police lieutenant at the time, to orchestrate the plot against Fesser.

In his deposition, Stradley said he knew Fesser had been seen with and attended trials of known gang members two decades ago. He told Portland’s gang enforcement officers that Fesser was a gang associate who had made threats against his boss. Testimony by the Portland officers showed they revered him as a law enforcement veteran and had no reason to doubt him.

Benson and Stradley later denied the claims in sworn depositions. According to reports, Fesser had been convicted in 2001 of using his phone in the commission of a drug-trafficking offense and sentenced to four years in prison. He has not been convicted of a crime since.

Stradley left the West Linn Police Department in January 2018 for a new role as a supervisor at the state’s police academy for the Department of Public Safety Standards and Training. He resigned in June after backlash from the case.

Officials told The Oregonian that the state would not be filing any additional criminal charges against others involved in the case.

“Without Timeus and Stradley, this is not justice,” Fesser said. “It’s like they’re trying to do something to say they did something.”