Last year, Kelley Williams-Bolar was convicted for “illegally registering” her daughters in a better, suburban school district outside of Akron, Ohio. In Connecticut, Tanya McDowell was also convicted, and sentenced to five years, for trying to send her son to a better school district.

What was the teachable moment from these incidents? For most, it was that a mother can be sentenced to five years in prison—egregious by almost any standard—for trying to get a better education for her children.

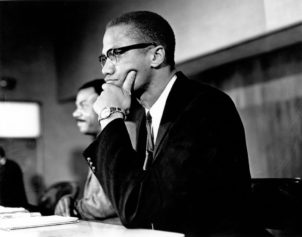

This week marks the 58th Anniversary of the landmark Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education, which was a precursor to monumental changes that would enforce important civil rights law associated with protecting equal rights and eliminating de jure segregation. But, it was also an important extension of a growing public will to re-imagine the promise of American democracy.

However, while de jure segregation may have ended in many ways with the Brown decision, affecting aspects of public policy well beyond the issue of education, Brown did not address the ways in which lingering xenophobia, tribalism, and the intersections between race and poverty would sustain de facto segregation.

It also did not anticipate other proxies for race that would later facilitate a re-segregation of the public learning environment, and potentially lead to different performance patterns and outcomes associated with public education in the United States.

Civil rights advocates didn’t anticipate that schools today would be more segregated than they were at the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

Today, according to the Civil Rights Project at UCLA, a third of all African American and Latino children sit in classrooms that are 90 to 100 percent African American and Latino, while the average White child in America attends a school that is 77 percent White.

While the racial achievement gap is slowly closing, about four in ten Black female students drop out of high school, compared to one in four girls overall who do not finish high school; and nearly a quarter of Black boys—as early as kindergarten—feel that they lack the ability to succeed in school. This is three times the rate for White boys.

While education is a human right, the U.S. Constitution does not guarantee it as a civil right. As a result, the quality and form of education being provided to students in each state varies to the extent that there are 50 unique states and the District of Columbia responsible for shaping its standards. Public education remains financially supported by state governments and, subsequently, local property taxes, which grant to school districts at varying levels a percentage of revenue that determine the quality of services and resources that are applied toward the education of students. This reliance on the local infrastructure has produced disparate access to education, primarily governed by racially and socioeconomically determined status of privilege.

A few weeks ago, the Institute for Research in African American Studies at Columbia University hosted a conference on the new vision for Black freedom. The conference convened dozens of radical scholars, students, artists and activists for a discussion about Dr. Manning Marable’s legacy and how to advance the Black freedom struggle. Black freedom in its most literal interpretation must be seen in connection to the expanding prison system—where more than 60 percent of inmates are illiterate—and within the even broader context of criminal justice supervision and surveillance.

In light of these conditions, is a new vision premised on human rights possible? Yes.

Read the rest of this story on Politic365.com