According to the Pew Research Center, Black people are the most religious group in the U.S., believing in God, and saying religion is an important part of their lives more than whites and Latinos. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

African-Americans are the most religious group in the United States, but what are they getting in return?

According to the Pew Research Center, 79 percent of African-Americans identify as Christian, as opposed to 70 percent of whites and 77 percent of Latinos. A majority of Black people belong to historically Black protestant churches, which trace their origins to the late 18th century. Smaller numbers of African Americans are evangelicals, Catholics, mainline Protestants and Muslims. The largest Black churches include the National Baptist Convention USA, Church of God in Christ, the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), the National Baptist Convention of America and the Progressive National Baptist Association Inc.

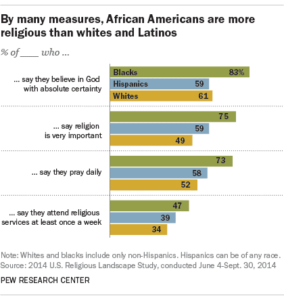

Pew found that more African-Americans believe in God — 83 percent — than whites and Latinos — 61 percent and 59 percent, respectively. More Black people say religion is very important in their lives — 75 percent versus 49 percent of whites and 59 percent of Hispanics. However, the number of religiously unaffiliated African-Americans is on the increase, and older Black people are more likely to be a part of historically Black Protestant congregations than younger people. These data on African-Americans and religiosity reflect a religious survey Pew conducted a decade ago.

These statistics on Black religious enthusiasm come amid reports of a Black exodus by those, especially young people, who seek traditional African spirituality, or perhaps are disenchanted with the hypocrisy and sanctimony of Christian evangelicals, and view Christianity as a ”white man’s religion” that will not speak out against institutional racism and is stalling Black liberation. While Black young people and millennials are leaving a “stale, stagnant church” that has not grown with them and has shown hostility towards their movements, as D. Danyelle Thomas, founder and content creator of Unfit Christian wrote last year, this begs the question: What of the many people in the Black community, those who face the greatest challenges in society and continue to be so religious?

Black people generally did not arrive in America as Christians, as most were followers of indigenous traditional faiths and 10 to 15 percent were believers in Islam. Christianity was the religion of the slave master and of white supremacy. And yet, Christianity was the faith of Nat Turner and John Brown, of abolition. Faith has been an important part of Black life for centuries, for people who turned to the Bible for hope and inspiration and created their own form of worship.

Dr. Eboni Marshall-Turman, assistant professor of Theology and African American Religion at Yale Divinity School, is highly critical of the Black church. However, she also readily points out the significance of the Black church and its role in the community. “If we take the premise that African-Americans are the most religious people in America, what are they getting in return presupposes certain kinds of materiality which are at stake for Black people of faith. But I think more integral to a Black Christian project is hope,” Dr. Marshall-Turman, a Christian theologian who served for ten years as assistant minister of Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, told Atlanta Black Star. She added that religion historically has oriented Black people to the world, “especially to a world in the U.S. that has denigrated Black life,” and has provided a “breathing space for Black people to survive and thrive” and “think about one’s own life and future outside white hegemony.”

“There is a material aspect beyond the project of hope and possibility that is part of the tradition the church. It is often one of the first places we go and the last place we find ourselves,” Marshall-Turman offered. “We will die, and a person of faith will stand over us and say final words. Whether we see ourselves related to the Black church in terms of membership, there is the lifespan in terms of our community; the Black church bookends from the blessing of babies to the funeralizing of the dead.”

There are tangible ways in which the Black church participates in the life of the Black community, the Black theologian notes. “Black churches feed the hungry, they support the homeless. They support those who may not have the basic necessities of life. They show up at court to support members of our community who have been unjustly incarcerated and find themselves in the throes if the criminal justice system,” she said. “They advocate in terms of basic necessities, housing, jobs, equal-pay services in the communities, very foundational basic matters of one’s right to life,” Marshall-Turman added, noting Black churches and mosques that go beyond offering hope and are “showing up” and serving people outside of their congregation, and handing out food on a regular basis.

D. Danyelle Thomas has a different take on the Black church and why people remain. “I would venture to say that most remain in relationship with the church because of both fear and familiarity. Even those with only a tangential relationship to church/faith, the fear of hellfire and brimstone as an alternative is enough to keep us captive,” Thomas told Atlanta Black Star, noting that hellfire, which she removed from her own theology, is not the dominant philosophy for most Black churches. “There’s also the facet of familiarity, as Black churches are more than places of worship, they offer community within community for us. Some of us still do church because it’s what we’ve always done. Like fear, familiarity has a stronghold on Black folks’ relationship with faith because interrogating the ‘why’ behind our actions isn’t always easy,” she added.

There is no monolithic Black church, and some African-Americans congregations have a long legacy or a present-day track record of fighting for social and racial justice. Black churches have fought on the front lines in resisting racism through slavery and the civil rights movement, and the AME Church was founded in resistance to slavery. A center of community life, the Black church often has been the target of Klan violence and white domestic terror, whether the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham in 1963, or the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston in 2015. However, Black religious institutions have also pacified the Black struggle. As beloved as Martin Luther King and Malcolm X are in the Black community, not everyone was with them and what they espoused when they were alive. Some Black churches have internalized white supremacy and have been accused of exploiting their congregations, and in the case of prosperity gospel, have appropriated white notions of capitalism for Black religious spaces.

Prosperity theology is alive and well, Thomas says. “The thing is, we all know we live in a system of capitalism that uses the tools of racism, sexism, classism, and the like to further hegemony. In my experience, I’ve found that the Black church is but a microcosm of the society at large. This is historically not the case, of course, as we know that the Black church was the cornerstone of the Civil Rights Movement and that faith has sustained our ancestors and living elders,” she said. “Logically, we understand that money answers all things so I don’t think people expect churches to operate for free. But, like with music and sports, churches have proved to be a fast-track to financial success with the right sales pitch — and that has, in my observation, elevated the visibility of Prosperity Theology or, as I call it, the business of church,” Thomas added.

According to Thomas, the pitch of prosperity theology is that an endless supply of wealth will be available to those who believe strongly enough. “There’s a bible verse that we’ve gleaned the idea that ‘only what you do for Christ will last’ (II Corinthians 5:9-10), and when you couple that with verses like Luke 6:38 (“Give, and it will be given to you. A good measure, pressed down, shaken together, running over, will be put into your lap; for the measure you give will be the measure you get back”), the formula of spiritual gaslighting writes itself. And many folks decide to stay because they’ve been stripped of critical analysis in Jesus’ name,” she said.

Many people, including Black people, are in a relationship of spiritual gaslighting with their churches, Thomas argues, which lays the foundation for why many remain in churches that are not empowering or growing them. “Spiritual gaslighting is feeling like you’re crazy or bad, being taught the inability to trust your own judgment, constantly apologizing, insane levels of guilt and a need to constantly justify your normal, everyday decisions to an implacable and hyper-critical external authority,” she noted, adding that this does not mean the church is inherently abusive, but rather that certain normalized aspects of church culture are at play. “Your reason, conscience, will, emotions, culture, and even your personal relationship with God are all continually under attack by demonic forces that are seeking to deceive you. Therefore, you should be automatically suspicious of anything that comes from either yourself or from a source outside of the ideological bubble,” Thomas said.

“Those of us who stay or, at least, keep a tenuous-at-best relationship with the church WHILE transforming our theology do so because we understand the importance of not throwing the baby out with the bathwater. We also stay because we believe in the possibility of building the new community that reflects our hopes,” Thomas said, while acknowledging that some people are fortunate to be in fellowship with ministries that focus on inclusion, mental health, social justice and other pressing concerns. “The latter, creating forward-looking fellowships, is the driver behind my work with Unfit Christian. My goal is to remove all things that restrict corporate access to God, including all the negative -isms and deafening silence on sociopolitical issues.”

“I think nothing is beyond critique. Black churches are not God. They are institutions built by human hands,” Marshall-Turnan believes. “if we want to strengthen the church and pursue the church as relevant to the Black community, we have to continually critique the church. I bet those who critique the church love the church, and believe in its transformative potential,” she said, noting the institution is historically sexist, homophobic, and transphobic, marginalizes young people and engages in economic fragmentation, which explain why young people are leaving the Black church.

“I’m not really concerned about the studies that show the increase in ‘nones,’ or that Black people are leaving the church. I feel the work of Antony Pinn is so resonant,” Marshall-Turman said of the Black atheist humanist scholar at Rice University who refutes the claim that all African-Americans are theists. “The narrative we’ve been hyper-religious people is not true, and when you think about the secular movements within the spectrum of the movement for Black freedom, it is obvious that every Black movement did not start in the church. So, it is not true that everybody has been in the church,” she noted, rejecting the alarmist argument about people leaving the Black church, and adding that with mobility and other societal factors, the concept of church itself is transforming.

“As a theological educator, I see the next generation every day. I see them coming with rigorous critiques of Black churches and also deep commitment to Black churches. … I also see young Black budding theologians who are imagining new ways of doing church, and I think the Black church as a rhetorical indicator is big enough to hold all of that. So I am not too worried about that. As an older millennial, I am not worried if the church will be here tomorrow,” she added, believing it will be in the hands of Black people such as these.

“The Black church has so much great potential to do transformational work. As it relates to everyday folks living in proximity to the church. Black churches matter,” Marshall-Turman concluded. “They just do, and they’re still held in high esteem behind this spirituality.”