By Chermelle Edwards

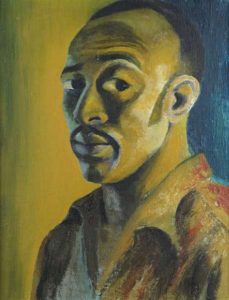

“Art is a human virtue and I have given my whole self to it—for it promotes understanding amongst races rather than destroy it,” said Gerard Sekoto.

A Black South African, Gerard Sekoto’s first love was music, his last, art. His first love began early, with a family reed organ, the harmonium, while growing up with his missionary father, and uncle in Bothsabelo near Middleburg, Eastern Transvaal, since named Mpumalanga. By the time he reached adolescence, art in the form of drawing with colored pencils and craftworks became his passion while attending Diocesan Teachers Training College in Pietersburg.

In his early years of creating art, a desire to express his own individualistic style emerged while teaching art school in Pietersburg. Upon winning second prize in an art competition—May Esther Bedford—he cemented his career in art in 1938, by seeking it as his official career. Leaving Pietersburg, Sekoto’s first stop was Johannesburg, where within a year, in 1939, he held his first exhibition.

He developed a friendship with artists Alexis Preller and Judith Gluckman, who taught him to work in oil. This made an indelible mark upon him, becoming a signature in his works. By the next year, in 1940, Johannesburg Art Gallery and Sekoto made history together, the former as the first museum collection to own art by a Black artist, and the latter by extension of their reciprocal relationship became the first Black artist to have worked owned by a museum collection.

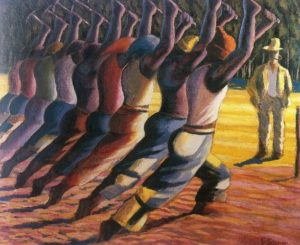

After the purchase, Sekoto created prolifically almost every consecutive year thereafter during the 1940s. Concerned with life in African townships, and the growing apartheid movement in South Africa, his artistic repertoire was full of these realistic themes, drawn in vibrant colors, which soon caused limitations on how successful he could be given the politics of his country. Undeterred to create, the most numerable and notable works produced by Sekoto in a year, is attributed to 1947, the same year he self-exiled to Paris because of apartheid.

Paris was a beautiful city for Sekoto to be inspired by, but a troubling one financially for living life as an artist. His other early love played a pivotal role in helping him make a living. He worked as a pianist singing Negro spirituals, contemporary French pop songs and playing jazz at l’Echelle de Jacob, a nightclub that thrived following World War II. Sekoto’s music was more than a means to support himself by way of a nightly gig, his music was also auto-biographical, capturing his exile from the oppression in South Africa which he vowed not to return to. A byproduct of that creative, yet tumultuous time, including illness and alcoholism, was the creation of 29 compositions published in Les Editions Musicales between 1956 and 1960.

Then, in 1960, a visit to Casamance for the Congress of Negro Artists in Senegal inspired a new direction for Sekoto, an artistic technique called gouache. Senegal rekindled memories of his childhood and his work took was influence by the recounting of these early South African times, current social times and the impression Senegal made upon him. Empowered to create, he pulled from the two genres that he loved as a child, making ritual music and art, although now, it was the inexpensive technique of gouache art, which he fancied and began to create with. Two of his most notable works with this method include “Blue Head” in 1961 and “The Three Figures” in 1968.

Throughout the 1970s, apartheid had an obvious strong hold

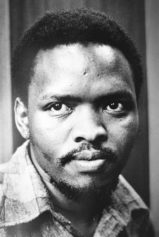

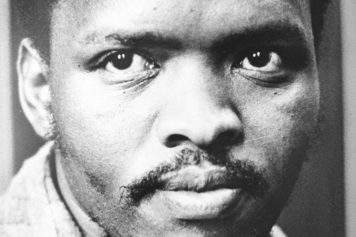

in Mpumalanga, and so it did in the political themes of his later works. While he remained concerned with his native homeland, two significant deaths impacted the artist personally in the mid-to-late seventies; his lover Marthe Bailon, who in 1976 died without a will, causing financial hardship on Sekoto. As well, the death of Steve Biko, who he honored with a painting in 1978, “Homage to Steve Biko”—which Sekoto claimed was stolen—and later became one of his most important created works of the decade.

It wasn’t long into the arrival of the 1980s that the exiled pioneering artist was destitute, selling metro tickets illegally and eventually hospitalized for nearly two years from a car accident. With the help of his nephew and a well-intentioned, educated woman from Johannesburg, Barbara Lindop, Sekoto was resurrected from his plight. Working with the African National Congress (ANC), Lindop, his nephew and Mongane Wally Serote of the ANC, his works were purchased and procured by the ANC as a national cultural heritage, with a revision of his career work, in the cities of London, Paris and Johannesburg.

Paris became the last home of Sekoto, for he never returned to South Africa, dying on March 20, 1993, one year before South Africa’s first democratic elections. While his home land went on to make history after his death, Sekoto made his mark during his lifetime drawing life, form life. Today, more than 3000 works of Sekoto’s, including paintings, papers and memorabilia remain accessible at the National Gallery in Cape Town by the Gerard Sekoto Foundation, an organization in his namesake, to uplift art education for young South African children. Thus, even in his death, Sekoto pioneers Black South African artists.