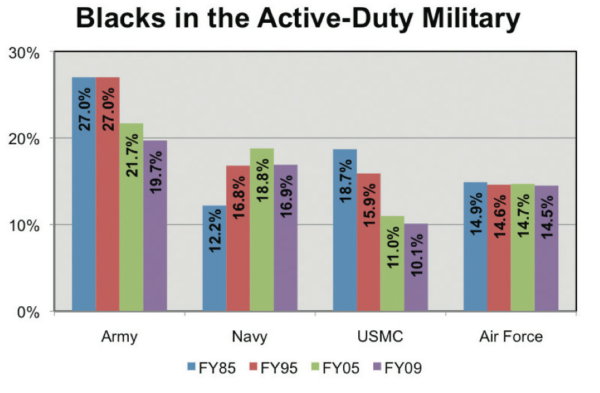

Over the three decades since the mid-1980s, the percentage of Black people in the Army has dropped from nearly 30 percent to 20.9 percent in 2009, according to a report on diversity in the military released by the U.S. Army.

In addition, a disproportionately high percentage of people dying in those wars were Black male and female soldiers.

More than 26 percent of the female casualties from the major wars between the 1980s and 2009 were Black women, while about 17 percent of the male casualties were Black men, according to a report released by the Defense Manpower Data Center.

Why are those percentages significant? Because during this time frame, young Black women of military age accounted for less than 13 percent of the female population in the U.S., while Black men made up about 14 percent of young men of military age, according to census figures.

This means that the American soldiers dying overseas were disproportionately African-American—particularly among the women. If a Black female soldier was sent to the Middle East, she was much more likely to die than her white female counterpart.

Among previous generations of young people, African Americans eagerly flocked to the armed services. During the Persian Gulf War back in 1990, Blacks made up more than 30 percent of the Army’s population—although they only made up 12 percent of the total U.S. population at the time, according to an article published by the Rutgers University Press back in 1994. That meant that nearly one out of every 3 American soldiers was Black.

Now the figure is closer to one out of every five. Perhaps more than a decade of soldiers coming out of Black neighborhoods and losing lives and limbs to war has significantly dampened the lure of opportunity.

In addition, a poll conducted by CBS in 2007 revealed that more than 80 percent of Black respondents were not in support of the Iraq War, meaning Black families probably were not as keen on their sons and daughters enlisting.

But that doesn’t mean the campaigns stopped.

The Army still uses ad campaigns in Black neighborhoods offering a life in the armed services as a great chance to get ahead. The campaigns, with their subliminal—and sometimes not so subtle—messages capitalize on the economic struggles in low-income Black neighborhoods. They specifically target young Black people and urge them to enlist, assuring them that the Army would serve as a brighter alternative to what would have been a bleak future.

For one 25-year-old African-American from New York who grew up in a small neighborhood in Macon, Georgia, with his seven siblings, those promises of a bright future with the Army were hard to resist.

It’s been a little over four years since the self-proclaimed former comedy king of his high school decided to skip his collegiate plans in order to serve his country. But his decision had nothing to do with national pride or feeling a sense of duty to fight for one’s country.

“None of that mattered to me,” the young man, who preferred to stay anonymous due to his active status in the Army, told AtlantaBlackStar in an interview last week. “I just knew it was time for me to do something with my life. I had to do something and that was it.”

Initially, he hoped to move back to New York to study graphic design, but with the cost of out-of-state tuition, the lack of financial aid and a single mother who still had four other children living at home, there was no extra money to fund those aspirations.

As with many young Black men and women, the Army seemed like the next best thing—in fact, the only other option.

The Army has been experiencing a public relations disaster in recent months in regards to African Americans. Though the Army has long been celebrated for its more progressive racial policies than general American society, the military division seems to have developed a tin ear for racial politics. Earlier this year, the Army issued regulations that banned many hairstyles that Black women wear on a daily basis. Secretary of State Chuck Hagel was forced to reverse that ban.

Just this past week, CNN broke the story that new Army regulations said it was acceptable to use the word “Negro” when referring to Black people.

That does not sound like a winning formula for attracting a groundswell of Black enlistees.