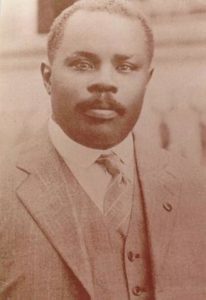

In fact, Marcus Mosiah Garvey personifies the excellence of African people. As a mass leader, propagandist, organizer and activist, Garvey had no peer. He ranks with the greatest of the great. His motto, “Up! You mighty race. You can accomplish what you will” continues to resonate with us. His influence and long-term impact are beyond dispute and he was a magnificent visionary for African people.

This year marks one hundred years since the founding of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, and so it gives me great pleasure to contribute a few words about this remarkable man. Indeed, it is a labor of love.

Marcus Mosiah Garvey, one of the greatest leaders African people have produced, was born August 17, 1887, in St. Ann’s Bay, Jamaica. He spent his entire life in the service of his people—African people. He was bold, he was uncompromising, and he was one of the most powerful orators on record. He could literally bring his audiences to a state of high energy with his fiery rhetoric and truth. In his speeches, actions, and ambitions, Garvey emphasized racial pride. His goal was the redemption and liberation of African people wherever they were found on the planet. His dream was the galvanization of African people into an unrelenting steamroller that could never be defeated.

At age 14, Garvey left school to work as a printer’s apprentice. As a young man, he participated in some of Jamaica’s earliest nationalist organizations, traveling throughout Central America and spending time in London, where he worked with the Sudanese-Egyptian nationalist Duse Mohamed Ali. Garvey was invited by Booker T. Washington to come to the United States to discuss the establishment of an industrial training school in Jamaica, but he arrived in 1916, a few months after Washington’s death in 1915.

Shortly after arriving in America, Garvey embarked upon an extended period of travel. When he finally settled down in New York City, he organized a chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, an organization that he established in Jamaica in 1914. Its motto was “One God, One Aim, One Destiny,” and its members pledged themselves to the redemption of Africa and the uplift of Black people everywhere. The UNIA & ACL advocated race pride, self-reliance, and economic independence.

When asked if he was African or Jamaican, Garvey responded in typical fashion. He exclaimed “I will not give up a continent for an island!”

Within a few years, Garvey, as the leader of UNIA & ACL had become the best-known and most dynamic African leader in the Western Hemisphere and perhaps the entire world. By 1920, the organization had hundreds of divisions in North, South, and Central America; the Caribbean; Africa; Europe; and even Australia. It created and operated an international shipping company called the Black Star Line, hosted elaborate international conventions, and published a weekly newspaper entitled The Negro World. No other organization in modern times has matched the UNIA & ACL for its prestige and the impact among African people.

Garvey understood the importance of history in the African liberation struggle, writing early that, “History is written with prejudices, likes and dislikes; and there has never been a white historian who ever wrote with any true love or feeling for the Negro.” He added that Black people should expect “but very little by way of compliment from the pen of other races.” “Every falsehood that is told by the historian,” he wrote, “should be unearthed, and the Negro should not fail to take credit for the glorious and wonderful achievements of his fathers in Africa, Europe and Asia.”

He added: “We are satisfied to know…that our race gave the first great civilization to the world; and, for centuries Africa, our ancestral home, was the great seat of learning; and when black men, who were only fit then for the company of the gods, were philosophers, artists, scientists and men of vision and leadership, the people of other races were groping in savagery, darkness and continental barbarism….Black men were so powerful in the earlier days of history that they were able to impress their civilizations, culture and racial characteristics and features upon the people of Asia and Southern Europe. The dark Spaniards, Italians and Asiatics are the colored offspring of a powerful black African civilization and nationalism. Any other statement by historians to the contrary is ‛bunk’ and should not be swallowed by the enlightened Negro.”

To counter the multiple falsehoods perpetuated by Eurocentric historians about Africans and other people of color, Garvey admonished his followers to take on the mantle of uncovering and decoding the African past:

“Negroes, teach your children that they are direct descendants of the greatest and proudest race who ever peopled the earth; and it is because of the fear of our return to power, in a civilization of our own, that may outshine others, why we are hated and kept down by a jealous and prejudiced contemporary world. The very fact that the other races will not give the Negro a fair chance is indisputable evidence and proof positive that they are afraid of our civilized progression.”

Garvey also had a broad vision of Pan-Africanism and of the African family of humankind.

He wrote: “When we speak of 400,000,000 Negroes we mean to include several of the millions of India who are direct offspring of that ancient African stock that once invaded Asia. The 400,000,000 Negroes of the world have a beautiful history of their own, and no one of any other race can truly write it but themselves. Until it is completely and carefully written, for the guidance of our children and ourselves, let us think it.”

In June 1965, the U.S. civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr., and his wife, Coretta Scott King, visited the shrine dedicated to Marcus Garvey in National Heroes Park, Kingston, Jamaica. In a speech delivered at that site, King informed his audience that Garvey “was the first man of color to lead and develop a mass movement.”

King further credited Garvey as “the first man on a mass scale and level to give millions of Negroes a sense of dignity and destiny, and make the Negro feel he was somebody. King was the posthumous recipient of the first Marcus Garvey Prize for Human Rights given by the Jamaican government. The prize was presented to his widow on December 10, 1968.

This is year one-hundred since the founding of Marcus Garvey’s UNIA &ACL. It is history. But I can’t help but wonder what Marcus Garvey would say to us today, if we could but hear his voice.

(This article is culled from Runoko Rashidi’s New Introduction to Marcus Garvey and the Vision of Africa, edited by John Henrik Clarke and published by Black Classic Press in Baltimore, Maryland in 2011.)

Runoko Rashidi is a historian, writer, lecturer and leader of African heritage tours. He is also the official Traveling Ambassador of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League. For more information about Runoko Rashidi write to [email protected] or go to www.travelwithrunoko.com