When Andrea Perez moved into her cozy rent-controlled apartment in East Hollywood, California, some 40 years ago, Apple was releasing its first personal computer. And a brash young real estate developer from Manhattan was celebrating his first GQ magazine cover

Perez, 53 at the time, had more modest goals than Donald Trump or Apple visionary Steve Jobs. She just wanted a nice home in a safe neighborhood where she could raise her family. Perez found that, along with stability — the home was owned by the same family since 1927.

Eventually, her daughter, son-in-law and grandson moved into the unit next door.

But last year, the fourplex was purchased by a real estate developer, Avenue Homes, with big plans that didn’t include the current tenants. They all received eviction notices, and their move-out date is just three weeks away.

“I feel sad,” Andrea Perez told NBC-4 in Los Angeles. “I would want to cry, but I don’t want to cry.”

Perez is not being evicted for falling behind on the rent. She just doesn’t pay enough, at least to her landlord’s way of thinking.

He’s making use of a California law, the Ellis Act, which was meant to empower small property owners, allowing them to evict tenants in rent-controlled units when the landlord is ready to retire. But according to one tenants rights group, big-time developers are taking advantage of a loophole in the law so they can replace long-term tenants with ones willing to pay higher rents.

“Landlords invoke the Ellis Act all the time. Especially for smaller parcels, two, three, four unit buildings,” said Joseph Tobener, a tenant rights attorney interviewed by NBC-4. “Local rent control jurisdictions have to allow landlords to go out of the rental business, according to state law.”

According to the LA Tenants Union, developers are pricing working-class tenants out of the city.

“Four thousand, six thousand dollars… that’s a lot of money for one apartment,” said Perez, noting just how high rents are rising in Los Angeles.

Gloria Mejia, Perez’s daughter, said families like hers are struggling to stay afloat while “companies with mega-money are using this law to their advantage, evicting people and doing whatever they want with the properties.”

And there’s little that tenants can do except hope for a procedural error, Tobener said.

“Nine times out of 10, I would say a tenant rights lawyer can find errors in the Ellis Act notice and get the tenant more time,” he said.

But eventually the clock runs out.

“We’re tired of this happening all over,” one tenant said at a recent protest. “It’s not mom-and-pop landlords anymore; it’s developers and corporations.”

And evictions are soaring across the nation now that eviction moratoriums and emergency rent assistance offered during the pandemic have ceased. Eviction filings have risen more than 50 percent in some cities, PBS reported in March.

During the first two years of the COVID-19 crisis, the mortality rate was more than twice as high for renters facing eviction.

“After two years of struggling to pay rent, I get faced with eviction, and all I could feel was my blood pressure drop,” Marcario Garcia of Dallas told “News Hour.” “During that moment, I saw myself in the street.”

“Your mind is just racing and it’s the one topic in your mind, eviction, eviction, eviction,” he said.

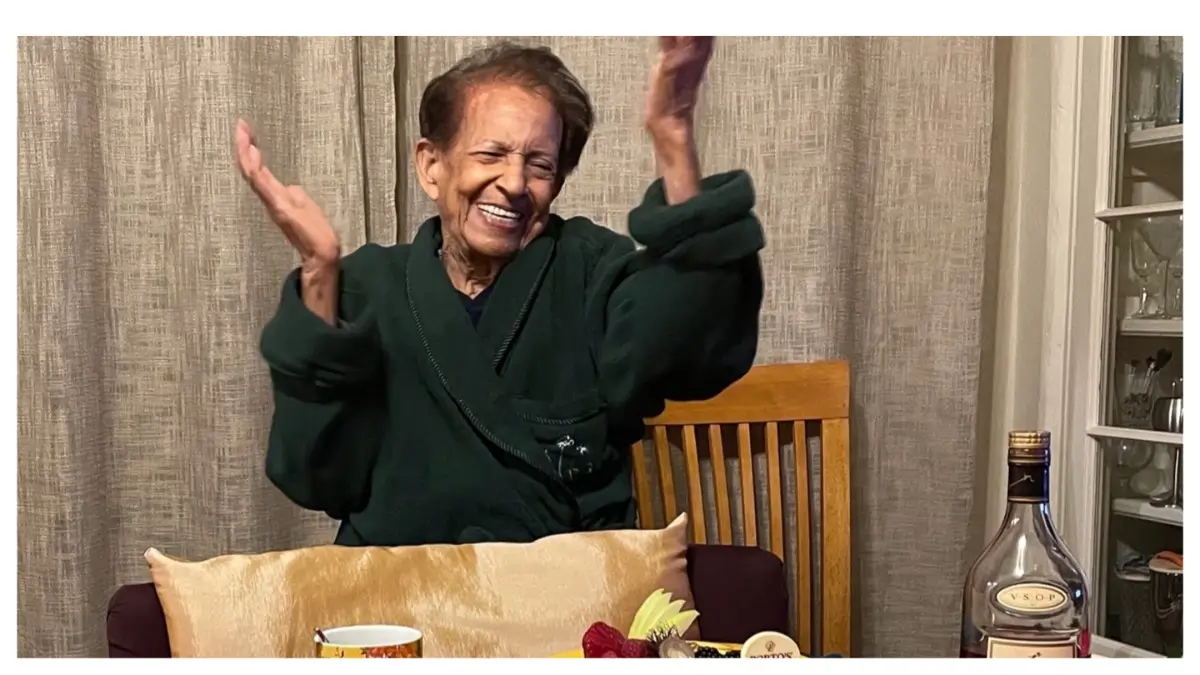

The Perez family will get $25,000 per unit. Friends and family have also set up a GoFundMe account for their 93-year-old matriarch which has raised just under $23,000 thus far.

But Mejia still worries.

“Now it’s like ‘Oh my God, I’m depending on other people to let me know if I can live in their house,’ because the place that I live in, where I’ve always paid my rent, they’ve told me I have to leave,” she said.

No matter where she ends up, Perez said her East Hollywood fourplex will always be home.

“All the time, I’m going to miss this place,” Perez said.