During this time of year, Muslims worldwide are observing the month-long practice of Ramadan, in which they abstain from food and drink from sunrise to sunset. It is only when the fourth call to prayer (adhan) is recited on sunset that the fast can be broken, marking a singular and relieving moment for millions of Muslims who have anticipated it all day.

While the call to prayer is a de facto sound and everyday reality in many Muslim countries, the adhan originates in a precious story in which one of the earliest Muslim figures, a Black man, rose to prominence from enslavement: The story of Bilal ibn Rabah, Islam’s first-ever caller to prayer (muezzin).

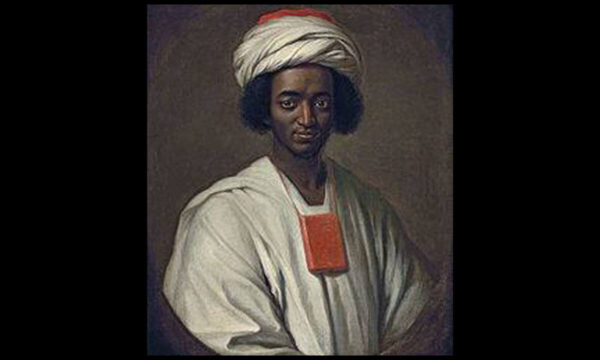

Bilal ibn Rabah was born or brought into enslavement in Mecca during the late 6th century, according to Professor Abdul Karim Bengura in an article on “African Roots and Transnational Nature of Islam” (2015). Other sources, such as Edward Curtis IV, professor of religious studies at the Indiana University School of Liberal Arts, claim that Bilal – a tall and handsome man with a thin beard – was of Ethiopian origin or that his mother may have been an Abyssinian princess.

Bilal’s early life was marked by hardship and oppression. His status as an enslaved person meant that he was often subjected to cruel treatment at the hands of the Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca, the Quraysh.

Bilal gave up idolatry and became one of the first followers of Islam after Muhammad announced prophethood and began to spread the word.

It is not clear when exactly Bilal converted to Islam, but this decision sparked derision and anger amongst the Quraysh who subjected the Abyssinian to torture, namely at the hands of Arab chieftain Umayya bin Khalaf and other nobles, as per “The Call of Bilal: Islam in the African Diaspora (Islamic Civilization and Muslim Networks)’’ by Curtis.

Bilal refused to give up Islam and repeated “ahad, ahad” (“one, one”), which refers to the existence of one God, even as Umayyah gave the command to place a hot boulder on Bilal’s chest.

Accordingly, Bilal, who endured physical and psychological torment from the Meccans yet refused to revoke his newly found faith, was set free by the companion and adviser of the prophet, Abu Bakr.

Bilal became one of the prophet’s constant companions. Due to the strength and melody of his voice, he was also appointed Islam’s first-ever muezzin, establishing the practice of calling faithful Muslims to pray five times daily from the tops of minarets (towers that are commonly a part of mosques).

Touched by Bilal’s strength and resilience, the prophet also appointed him treasurer, and in this role, Bilal gave money to less-advantaged individuals who couldn’t support themselves, including widows, orphans, and travelers. Moreover, Bilal fought alongside the Prophet in many battles and conflicts, eventually locating and killing Umayya, his former tormenter.

Bilal’s journey from enslavement to becoming the Prophet’s companion was not without its challenges, however. As a former enslaved person, he faced skepticism and criticism from Meccans and members of the Arab community.

In “Islam and Blackness’’ (2022), Georgetown University Islamic studies professor Jonathan A.C. Brown describes how Meccans would mock Muslims for having “no one better” than Bilal for the call to prayer, racistly calling the devout figure a “crow.”

Bilal would also face challenges and denial of marriage due to his skin color and former status.

Brown explains assertively that, “In Arabia at the dawn of Islam, the worst situation to be in was that of an outsider, to be marginal, whether one was a captive taken near Antioch or from Ethiopia. Blackness was seen as one of its potential markers.” Nonetheless Bilal’s unwavering faith and dedication to the teachings of Islam ultimately won over his critics and earned him a place of honor in the early Muslim community.

According to the “Call of Bilal,” he relocated to Syria during the reign of Umar, the second caliph, and joined the military effort to conquer the Levant. He passed away between the years 638 and 642 C.E., which was little more than ten years following the Prophet’s passing and is said to have been buried in Syria at the Bab al-Saghir cemetery.

Bilal’s legacy of perseverance continues to inspire people to this day. His steadfastness and resilience in the face of adversity serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of standing up for one’s own beliefs, even in the face of overwhelming odds.

Moreover, Bilal’s pivotal role in the early Muslim community cannot be overstated.

In the 1982 article, “From Black Muslim to Bilalian: The Evolution of a Movement,” Vassar College religion and Africana studies professor Lawrence H. Mamiya connects Bilal’s story to the intersection of Muslim and Black identity in the United States.

One of the late scholar’s interviewees asserts: “[…] The fact that Bilal was an African slave means that there is identification with that part of our history and oppression. There is an African root. But also, Bilal was an important figure in Islamic history. It means that we have a claim, a stake in the very beginnings of Islam.”

His story is also all the more significant for the Muslim community worldwide, which is the fastest-growing religious group in the world and whose racial affiliations are diverse from one country or continent to the next.

Bilal’s story serves as a testament to not only Muslims but also the Black community to the power of resilience and the ability of individuals to rise above their circumstances and make a long-lasting impact. That example reverberates to this day and is etched in the annals of history.