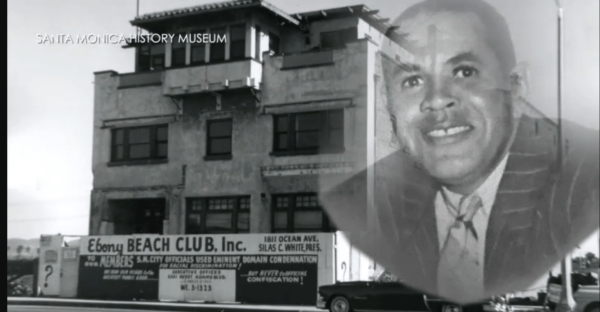

Ninety-year-old Connie White says her father, Silas White, always wanted to do something for his Black community in Santa Monica, California.

Several decades ago, her father opened a laundromat across from Santa Monica College, along with two real estate offices and a successful hamburger stand in the area.

Still, he wanted to do more, Connie said.

“He continued to think and think; his mind really ticked like a clock,” she told Atlanta Black Star. “He started thinking more specifically about a beach club for his people.”

She recalls being as young as 3 years old going on weekly beach trips with her father, who would only let them stay a short while because there was no place for them to change clothes other than the restroom or in their car.

Silas White’s dream of opening the Ebony Beach Club in Santa Monica would have solved that problem while also offering a space for Black artists and musicians to entertain in a location free of racial discrimination.

He envisioned the location of his club, which the family said he described as becoming “one of the best establishments in America for lodging and comfort of my people,” at the former Elks Club building on Ocean Drive in Santa Monica.

It had sat vacant for 13 years prior to Silas’ acquisition of the property in 1957, according to Where Is My Land, a small team of six that works to help hundreds of Black families find and reclaim land taken from them dating back to slavery.

Connie says her dad went through the proper steps of obtaining permits. All seemed to go well — until the city of Santa Monica stepped in, putting an end to Silas’ dream before it began.

The city used eminent domain to take Silas’ property, claiming they needed the land for a city parking lot. Silas fought the city and argued Santa Monica had not once tried to claim the property during the 13 years it sat vacant.

He erected a large sign on the building accusing the city of discrimination. The property would never become the Ebony Beach Club.

Silas and his investors asked to be awarded from the court $125,000 to cover the property and liability incurred for fixtures and equipment for the building’s renovation, according to research from historian Alison Rose Jefferson.

However in August of 1959, the court instructed the jury to consider only the land value in the case, and the racial discrimination charges were ignored.

Silas White lost his court challenge.

The jury determined that Santa Monica “would have to pay the Ebony Beach Club $74,000 in condemnation compensation” for the property, according to Jefferson.

Appealing the decision turned out to be futile, and the city began accepting demolition bids for the site in January of 1960, the historian added.

The building was knocked down that year – and the proposed parking lot was never built, according to Where Is My Land.

“The reason that they took it to begin with was because he was a Black man trying to create a space for Black people,” said Milana Davis, Connie White’s cousin.

The Viceroy Santa Monica Hotel now sits on the land. Today, Silas White’s family is urging Santa Monica to repair the injustice done to Connie’s father six decades ago.

Silas died in 1962 at 57 years old without seeing his dream realized.

“What the family wants is that land back and they want to be compensated for almost 60 years of lost wealth and income,” said Kavon Ward, CEO and founder of Where Is My Land. “That is justice.”

Bruce’s Beach Success Restored Families’ Hope

Like the White family, hundreds of Black families share similar stories of attempting to reclaim land stolen from them – like the Bruce family who successfully reclaimed land of Bruce’s Beach in Manhattan Beach, California, nearly a century after it was seized through eminent domain, Atlanta Black Star reported previously. (The Bruce heirs sold the land back to Los Angeles County for $20 million six months after it was returned to them in June 2022.)

In some cases, land was outright taken from Black people. In other cases, white people burned paperwork showing proof of rightful ownership. “Some people were run off of their land, with threats of being killed, and they came back to white people owning their land,” Ward said.

Before the Bruce’s Beach case, which Ward says marked the first time Black people had land returned to them in the United States, some families who’ve contacted her had given up hope.

“They’ve been working to get their land back for 30, 40 years, and now that hope has been restored,” Ward, whose team launched a Change.org petition for the White family, told Atlanta Black Star.

“Now, more people are reinvigorated, they’re ready to fight,” Ward said.

The White family is among them. They first learned of Where Is My Land and their efforts to help Black families in 2021, and reached out to the organization.

“Connie struck me because it was almost the same exact thing that happened to the Bruce’s; it was a racist city not wanting Black people to take up space near the water,” Ward said.

With Where Is My Land’s help, the White family has taken initial steps with the City of Santa Monica to rectify the wrong that was done to Silas White.

Gaining Ground Toward Reclaiming Stolen Land

Ward’s organization works on research, contacts attorneys, attends city council meetings and spreads the word online to draw attention to the White family’s case.

In December, Where Is My Land addressed a letter to Santa Monica calling out the city for being “anti-Black” and “systemically decimat[ing] Black communities and entrepreneurship.”

The letter stated, “Material acknowledgement is long overdue. Where Is My Land demands that you start with the White family.”

The city has previously acknowledged racial injustice and discrimination in its community’s history and said it’s “actively pursuing initiatives to rectify the lingering consequences of discriminatory city policies.”

On Jan. 24, Where Is My Land and the White family met with the one city council member who responded to their meeting request — Caroline Torosis, along with city manager David White — to discuss the family’s demands.

They say they initially heard “a lot of excuses” and “whataboutisms” at the meeting.

“‘If we give the land back to Connie, what about the Native Americans, or what about the Latin Americans,’ and I had to let them know that right now, we’re centering Black people and that’s OK, because when other groups fight for their causes, no one has asked them to center Black people,” Ward said.

They were also told regaining the land would not be an easy task and that they needed to figure out how to rally the support of other city council members.

As of now, they have at least two members including the city manager who may be on board, according to Ward.

The White family needs four of the seven city council members to vote yes in order for the family to get closer to reclaiming Silas’s land.

“We’re gaining ground,” Ward said.

Connie said her father would be “overjoyed” if he could see the progress the family is making in getting his land back.

“This was his dream, his vision, and to see something good happen, there’s no words to describe all that he would say and feel,” Connie said.