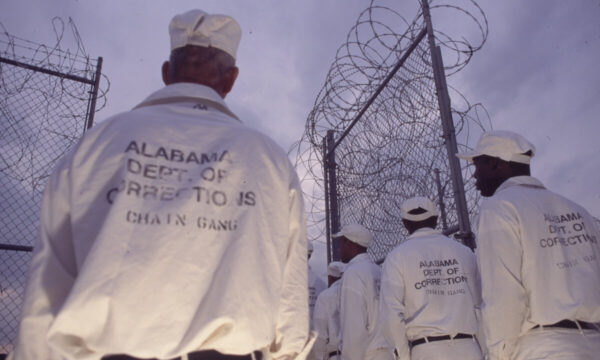

The families of two Alabama prison inmates who died in the past few weeks are demanding answers from state authorities after they received their loved ones’ bodies bizarrely missing several of their major internal organs.

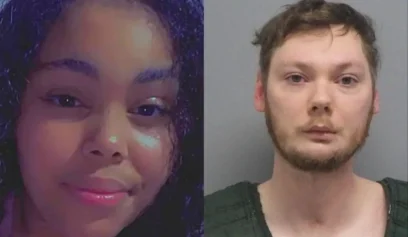

Both these cases raise questions about the treatment and mismanagement of the bodies of 74-year-old Charles Singleton and 43-year-old Brandon Dotson, who were inmates in the custody of the Alabama Department of Corrections.

Singleton died more than two years ago at a hospital that typically provides care for older inmates. Dotson was found dead two months ago in his cell at Ventress Correctional Facility.

In Singleton’s case, the University of Alabama-Birmingham’s Department of Pathology conducted his autopsy before returning his remains, WPDE reported. Court documents note that his family members had his body sent to a funeral home where the funeral director told them it “would be difficult to prepare his body for viewing” since it was already in a “noticeable state of decomposition” and was suffering from “advanced skin slippage.”

The family was also informed that Singleton’s body was missing all of his organs, including his brain. The funeral director told the family it’s common practice during an autopsy to remove internal organs and place them in bags but that they should be placed back inside the body once the process is complete.

Singleton’s family contacted the university about the organs’ whereabouts but reportedly received little to no information on the matter.

UAB released this statement in response to the lawsuit Singleton’s family filed:

“We do not comment on pending litigation. We only conduct autopsies with consent or authorization and follow standard procedures equitably for anyone consented to or authorized for an autopsy. The autopsy practice is accredited by the College of American Pathologists and staffed by credentialed physicians who are certified by the American Board of Pathology. In an autopsy, organs and tissues are removed to best determine the cause of death. Autopsy consent includes consent for final disposition of the organs and tissues; unless specifically requested, organs are not returned to the body. UAB is among providers that – consistent with Alabama law – conduct autopsies of incarcerated persons at the direction of the State of Alabama. A panel of medical ethicists reviewed and endorsed our protocols regarding autopsies conducted for incarcerated persons.”

Dotson’s case was also full of holes for his family members.

His mother requested state authorities to return his body as soon as his family learned of his death in mid-November.

The Alabama Department of Corrections conducted an initial autopsy before returning his remains five days after his death. When the family sent his body to a funeral home, the funeral director said Dotson’s body was severely decomposed, making plans for an open-casket funeral impossible. The family was also reportedly told the body could have been improperly stored while it was in the state’s possession.

Family members hired an independent pathologist to carry out a second autopsy and discovered that Dotson’s heart was missing from his body.

In a federal lawsuit, they alleged that the Alabama Department of Corrections kept his heart without the family’s consent. They also named the University of Alabama System a defendant in the belief that the university’s Heersink Medical School was a “possible intended recipient” of Dotson’s heart.

The school denounced the claim outright, calling it a “bald speculation,” adding that the university never conducted the autopsy or received Dotson’s organs.

The Alabama Department of Corrections offered no statement, telling ABC 3340 that it doesn’t comment on pending litigation.

Lauren Faraino, the attorney representing Dotson’s family, recently commented on Singleton’s case, citing that it proves that “this is absolutely part of a pattern.”