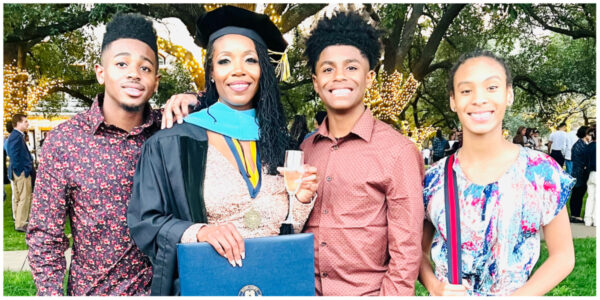

Donning a black graduation gown with three bars on the sleeve, Brandie Medina waited nearly 20 years for the moment she walked across the graduation stage to receive her doctorate degree.

On Dec. 9, Medina, 42, made history when she became the first Black woman to receive a doctorate from St. Edwards University.

Medina’s esteemed accolade is the culmination of a 20-year journey that includes motherhood, homelessness, surviving an abusive relationship, and finding her purpose and passion in life.

“I feel like I broke through so many barriers being the first Black woman, personal barriers as well as educational barriers,” said Medina, who is from the small coastal town of High Island, Texas.

Medina grew up in Galveston, Texas, to parents who believed in a good education. Both of her parents attended St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas, and earned their degrees from the private Catholic University that first opened its doors in 1841.

Her father, now deceased, served in the military and earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the school in theology. He went on to serve as a Baptist minister while also serving in the military. After military service, he dedicated his life to teaching special education students. Her mother earned her degree in biology before going to medical school to become a physician.

Medina’s education was spent in private schools. Once she began readying herself for college, her parents were eager for her to follow in their footsteps at St. Edwards, but Medina set her sights on finding a fit in the nation’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

“I’ve been around white people my entire life,” Medina said of her upbringing. “I really needed to understand my culture, and that was my biggest reason for going,” she continued.

The Texas native broke family protocol and opted for one of the HBCUs, to the dismay of her parents.

“They were livid because they raised me, not to necessarily follow behind their footsteps, but they wanted more for me, and they wanted me to go to a predominantly white institution,” Medina said of her parents’ reaction to her college-related decision.

Medina, on the other hand, said she felt like something was missing from her identity that one of the country’s HBCUs could help fill.

“I’m not going to lie, I would get around other Black women and Black friends, and there’s a lot of things I wouldn’t understand. I went off to an HBCU to understand who I was as a Black woman trying to navigate life,” Medina said.

Medina attended Prairie View A&M University, the state’s second-oldest public institution of higher education. The university opened its doors in 1876 and is situated in Prairie View, Texas, roughly 50 miles northwest of Houston. At Prairie View, Medina studied architecture before planning to enter the U.S. Air Force.

“I planned on going into the military just like my parents did,” Medina said.

Medina says she enjoyed her time at Prairie View A&M and felt connected to cohorts that shared similar values and experiences. When 2002 rolled around, she was preparing to graduate with her bachelor’s degree from the HBCU and then go into the military. Little did she know, her parents’ mindsets on the school took a 180-degree turn.

“My parents had already enrolled me into the master’s program at Prairie View, and I knew nothing about it,” Medina said to her shock at the time.

As part of her master’s program, Medina continued studying architecture abroad in Southern France.

Once she graduated with her master’s degree, she still considered a career in the military, but ongoing Middle East conflicts quickly changed her plans. The U.S. military’s involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan persuaded Medina’s parents to push their daughter in a different direction, effectively killing her military plans.

Back in Texas, Medina had to decide her next steps. She tapped into one of her passions: working with children. She applied to be an elementary school teacher, which began her next life chapter.

While working as a teacher, she realized the added challenges Black students face due to deeply rooted racism among the faculty and staff. Medina says the slights and microaggressions can be so subtle they are hard to notice.

“When you hear white teachers say, ‘those kids,’ or ‘those kids from the other side of the track.’ They don’t even give these students eye contact; it’s like when they come in, they turn their back to them.”

Her desire to improve the lives of Black children helped motivate her to go back to school and pursue her doctorate. She looked to her family’s alma mater and the new doctorate program the university launched in 2019. Medina wanted to move into a school administrative role and make a greater difference in children’s academic experience. She enrolled in St. Edwards’ Doctorate of Education of Leadership and Higher Education program.

Medina’s pursuit of a doctorate makes her part of a small cohort of professionals within the U.S. The National Science Foundation’s Survey of Earned Doctorates says, “only 4.4 percent of doctoral degrees are earned by Black women,” as reported in Forbes.

From 2010 to 2019, Black women saw gradual increases over the years in the overall number of doctorate degrees being issued. In 2010, 1,403 Black women earned doctorate degrees. In 2019, 1,832 Black women were awarded doctorate degrees, according to the Survey of Earned Doctorates. By comparison, 12,525 white women earned doctorate degrees in 2010; and in 2019, 13,216 white women earned doctorate degrees.

“Being a Black woman in higher education, you’re going to put up with some bulls–t,” Medina said of challenges Black women face while pursuing advanced college degrees.

Medina believes the added microaggressions and the feeling of isolation hinder more Black women from pursuing doctorate degrees.

“I think that’s why, it’s not that we can’t but it’s the barriers and hula hoops we have to go through,” Medina said of why she believes more Black women choose not to pursue doctorate degrees.

At the surface, Medina was well-educated, she had a thriving career she enjoys and a family of her own. The mother of four says beneath the surface, her life was in turmoil.

“As successful as I am in my professional life, that’s nowhere near where I am in my personal life,” Medina said.

Medina says for years she was experiencing multiple forms of abuse, including physical, sexual, emotional and financial.

As she pursued her doctorate degree, Medina felt the abuse reached a boiling point and she wanted out of a romantic relationship. She opted to move into a shelter in March 2022 rather than involve the police. She took her two teenage boys who were left in the home and took a few items of clothing and left.

The aspiring doctoral candidate was homeless for five months. While her boys eventually moved back into the house with their father, Medina did not return. She admits juggling multiple responsibilities from parenting to teaching and studying was difficult. She recalled a phone call from her school principal, asking her for shirts to wear because she had none of her own after moving into the shelter with nothing more than the clothes on her back.

“I’m at a homeless shelter right now. I have a pair of jeans I can wash and wear, but I need some school shirts just so I can get back and forth,” Medina said, recalling a conversation with her principal.

“It was making it very difficult for me to transition into another job because their internet service was sucky. I had to leave the shelter on the weekends to go to the library so I can do my schoolwork,” she added.

Medina says despite her multiple stressors wearing her down, she believed earning a doctorate degree could be the thing that turned her personal life turnaround. As the fall St. Edwards’ commencement ceremony inched closer on the calendar, Medina chose to work even harder.

“I felt like if I could push through whatever barrier I was going through at that moment, I would be so much more successful on the other end,” Medina said.

Her perseverance paid off as she completed her dissertation entitled, “The Intersectionality of the Professional Black Woman in Education Administration,” clearing the way for the once elusive doctorate degree she kept her sights set on despite a slew of trials and tribulations.

Tom Sechrest, director of the Doctorate of Leadership & Higher Education Program, said of Medina, “Brandie persevered through really challenging personal circumstances to complete her coursework.”

He went on to praise her dissertation on the intersectionality of Black women in education.

“Women of color are underrepresented in leadership roles in educational administration, and Medina critically examined why and then examined ways in which they might continue to overcome impediments,” Sechrest added.

“Nearly every member of the school’s first graduating cohort of doctoral students is a person of color,” the Austin Statesman reported.

As she continues to adjust to the title of ‘doctor’ before her name, Medina says she plans to continue working as a school administrator in High Island, Texas, and improving the educational experience for children of color.