Georgia officials have increased funding and changed policies to crack down on gangs for the past four years, but the gang problem in the state continues to flourish.

Experts believe the rising gang violence coincides with a national post-COVID-19 crime spike, and others think the state’s approach exacerbates the problem and inadvertently continues a cycle of violence.

Social policy advocate and attorney Miracle Jones told Atlanta Black Star lawmakers should try a different approach in tackling gang violence.

“Instead of making our police war-ready occupiers of our neighborhoods, let’s invest in our communities. Let’s invest in our schools. Let’s invest in health, shelter and safety of Black people,” said Jones, who spends time living between Pittsburgh and Georgia. “Let that be an option because you’ve never done it — adopt a neighborhood.”

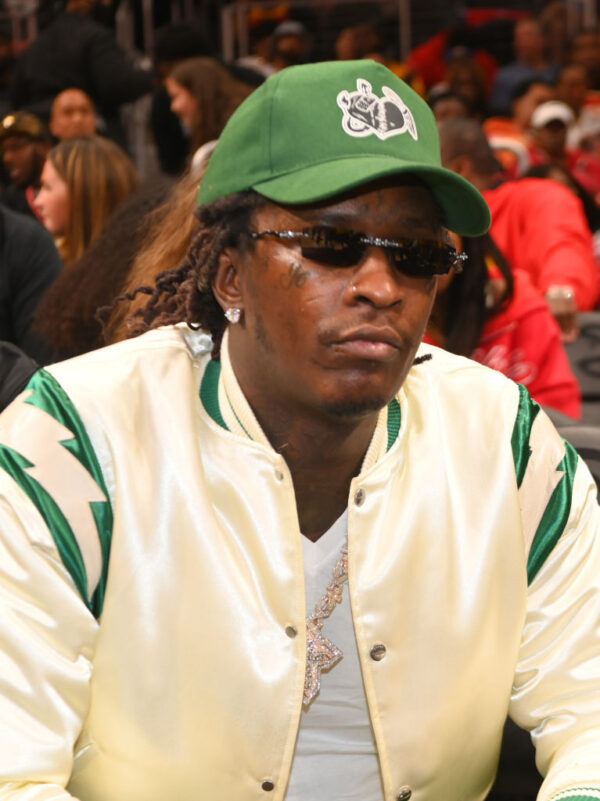

On May 10 while announcing the high-profile arrest of accused street gang founder, rapper Young Thug, Fulton County District Attorney Fanni Willis said gangs are committing 75 to 80 percent of the crime in Atlanta.

The rapper, whose legal name is Jeffrey Lamar Williams, was charged with conspiracy to violate the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act and participation in criminal street gang activity.

While the rapper’s arrest brought national attention to the rising crime in the metro Atlanta area. Atlanta is not alone.

Ken Howard, Georgia Bureau of Investigation special agent in charge, told the Buckhead Safety Task Force in March all of the 159 sheriffs in Georgia say gangs are the No. 1 threat in their counties.

Howard is pessimistic about the state’s ability to combat the problem.

“We’re not going to eliminate it. We are not going to win, for lack of a better term, but we can lose,” Howard told the task force. “We’ve got to work hard to push it back and then hold a line somewhere.”

Data show Georgia Bureau of Investigation investigated 446 gang-related cases across 100 Georgia counties and charged more than 170 gang members in 2021. According to Attorney General Chris Carr, there were about 71,000 validated gang affiliates in the state in 2018. About 50,000 were in Atlanta.

Carr launched the Anti-Gang Network in 2018 in response to the problem.

During the network’s February meeting, Carr said gangs were responsible for 60 percent of the violent crimes in the state.

Gov. Brian Kemp has made gang violence one of his top priorities, proposing and approving more spending to combat crime, including increasing personnel, bolstering crime lab resources and launching the GBI Gang Task Force.

In the 2022 session, lawmakers approved legislation to create a gang unit in the attorney general’s office and made it easier for Carr to collaborate with local district attorneys to prosecute gang offenders.

Georgia’s gang statute also creates a sentencing enhancement, adding harsher penalties to other crimes. GBI press announcements show that task force made arrests for street gang activity or violating the statute. The state agency has also announced arrests of “validated” gang members of well-known gangs.

It is unclear where the bridge between criminal gang activity and validation meets. GBI officials did not respond to questions from Atlanta Black Star.

Under Georgia law, a criminal street gang is three or more people formally or informally associated with certain crimes. There are wide range of crimes that fall under that category.

“It’s not the just the violence. It’s everything from car break-ins, to burglaries, to human trafficking, to shootings, so all spectrum of crime,” Willis told 11 Alive.

Dean Dabney, a professor and chairperson in the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology at Georgia State University, said gangs are “loosely defined.”

“Notoriously across the country defining a gang historically and geographically has been a challenge,” Dabney told Atlanta Black Star. “Because you’ve got to figure out how to include collectives that are committing a crime and exclude the Girl Scouts.”

In 1991, a group of 25 Girl Scouts was initially denied entry to a California mall because the mall’s anti-gang rules barred access to groups of more than three people.

Georgia’s gang statute goes on to say the existence of a gang may be established by “evidence of a common name or common identifying signs, symbols, tattoos, graffiti, or attire or other distinguishing characteristics, including, but not limited to, common activities, customs, or behaviors.”

Dabney said there is a noticeable increase in gang violence in the Atlanta metro area, but no one has a “clear understanding” of what’s driving it. However, he believes the pandemic has contributed to the change. Georgia lifted its COVID-19 restrictions before most other states, which attracted transients to the area, Dabney said.

“That presented a lot of opportunity for cultural conflict. People that are used to Atlanta kind of way of doing things, so to speak, come into contact with people from other cities, and that produces kind of beef on the internet, and that can lead to violence on the streets,” he said.

The pandemic also made it difficult for law enforcement to patrol neighborhoods spurring higher crime rates, Dabney said. It is easy for public officials and politicians to see a focus on gang violence as a fix for the crime problem that has erupted, he said.

“I think it’s both an emphasis on it, and then on the ground, change in the scope and dynamics of gang violence that has led to this kind of increased aggressive orientation toward it,” Dabney said. “I mean, it’s hard to be for gang violence. It’s one of those kinds of things — low-hanging fruit, if you will.”

Dabney said a RICO charge is a more “aggressive and creative way” to deal with complex gang activity.

Any person involved in a pattern of criminal activity motivated by or resulting in financial gain, physical threat, or injury can be charged with a RICO offense, according to law firm Pate, Johnson and Church. Georgia law currently lists about 50 types of offenses under the RICO law.

Willis used the RICO law to prosecute Atlanta Public Schools teachers and school administrators convicted of a standardized testing cheating scandal in 2015.

“It’s just the assertion that it is being done in a complicit and sustained manner,” Dabney said.

Pate, Johnson and Church says the state must also prove that a person is guilty of two underlying offenses and somehow benefited from the criminal acts or was “employed by or associated with an enterprise through a pattern of racketeering.”

Jones takes issue with how RICO cases are investigated. Investigators surveil offenders and allow them to commit more crimes instead of intervening, she said. For instance, investigators used evidence for some defendants in Williams’ case from more than five years ago, the indictment shows.

“There’s not an intervention that goes into place and says, ‘Hey, here’s some mental health resources. Here’s some job training resources,” Jones said. “’Here’s some anger management or rent diversion programs.’ It’s literally let’s get more funding to watch people do these violent harm.'”

Jones says the approach creates a cycle of poverty in neighborhoods where people often commit crimes to fill financial gaps. It also increases the strain on overflowing jails and prisons, she said.

“Our system right now says, when someone does a bad thing, we just let it keep occurring and occurring until we have enough evidence to put them away and maybe they’ll get convicted. Maybe not,” she said.