Victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre are one step closer to being compensated for the devastation and lingering effects of the deadly 1921 racial attack.

An Oklahoma judge has denied part of the most recent motion by the defendants to dismiss the reparations lawsuit, filed against the Board of County Commissioners, Tulsa Metropolitan Area Planning Commission and Tulsa County Sheriff.

Along with Tulsa, Oklahoma Military Department, Tulsa Chamber and the Tulsa Development Authority, they have fought paying reparations for decades. Defense attorneys tried to block the new case, filed in March 2021 from moving forward for over a year.

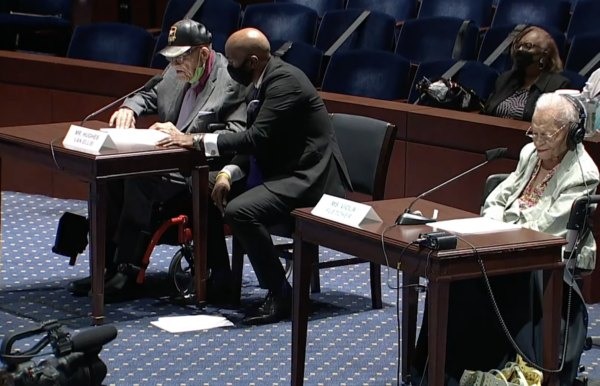

The plaintiffs are 11 survivors and descendants of Black residents of the Tulsa community destroyed by fire and bloodshed in 1921. The three remaining survivors are now over a century old and are among 100 residents who have been seeking reparations since right after the riots. The cases have been suppressed by the Ku Klux Klan and the Jim Crow era, but those who remain are hopeful in light of the judge’s ruling Monday.

“I’ve never seen nothing like this happen,” said Hughes Van Ellis, 101, a survivor of the massacre. “That means it’s going to change things. It’s going to make people think … It’s going to change, it’s going to be better for everybody.”

The current lawsuit asks for a special fund for the victims and their descendants of racial riots dubbed the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, which left 300 people dead and a thriving Black neighborhood incinerated. The devastation left tens of millions of damages in today’s money and evaporated generational wealth in the affluent community.

The victims also want the defendants to officially declare that the actions of that day and the century that followed “created a public nuisance” for the former Black residents of the Greenwood District and their offspring under Oklahoma law.

The lawsuit alleges that the city and insurance companies never repaid victims for their losses, and city officials stopped them from restoring the community. As a result, the riot ruined their economic standing, the lawsuit says.

The defendants argued that the case should be dismissed because some plaintiffs have not proven they directly suffered because of the massacre and that the court could not rectify their alleged damages.

Defense lawyer John Tucker argued that the massacre happened too long ago for the public nuisance law to stand. He also said the victims should be redressed by the legislature and not the judicial system.

“What happened in 1921 was a really bad deal, and those people did not get a fair shake … but that was 100 years ago,” Tucker said.

U.S. District Court Judge James O. Ellison also ruled in 2004 that the victims could not receive reparations because the massacre happened too long ago.

Damario Solomon-Simmons, an attorney for the plaintiffs who also worked on the case back then, said the new lawsuit might be the victims’ last chance for justice.

“We want them to see justice in their lifetime,” Solomon-Simmons, said, choking back tears. “I’ve seen so many survivors die in my 20-plus years working on this issue. I just don’t want to see the last three die without justice. That’s why the time is of the essence.”

Viola Fletcher and Lessie Benningfield Randle, the other two survivors, are 107 years old. The three victims were small children when the massacre occurred.

According to a state-sponsored commission’s 2001 report, the riots began on May 31, 1921, after a white mob attempted to lynch Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old shoe shiner. Rowland was riding in an elevator with a white teenager named Sarah Page, and she reportedly screamed.

The mob accused Rowland of sexually assaulting Page. The report says Rowland tripped and grabbed Page’s arm for support. Black residents went to confront the group when a gunshot dispersed the crowd. Outnumbered, the Black residents retreated to the Greenwood District.

The next morning, on June 1, 1921, the Black neighborhood was looted and set ablaze by white rioters for 24 hours. More than 1,250 homes and two hospitals were destroyed, according to reports. Thirty-five blocks were left charred by the racial violence. The commission estimated the final toll of the damage is $27 million in today’s dollars.

The attorneys must now gather evidence to support their arguments. Solomon-Simmons said so much remains unknown about the massacre, but there are photos and insurance claims, unlike other instances of racial injustices in America. He believes the trial could pave the way for similar cases to be resolved.

“If Black people can’t win this, how can we win?”