When Aliyah Griffith told her parents that she wanted to be a marine scientist at 5 years old, they thought it was just a phase.

Like any other toddler, one obsession quickly followed the next. First, she wanted to be a ballerina and then a doctor, but after Griffith saw a marine biologist training dolphins at the Baltimore Aquarium, her fascination with the ocean, atmosphere and animal life never faded.

Once her parents realized she was serious, they catered to Griffith’s interest by taking her to the best aquariums and frequent trips to Sea World. Years later, Griffith is the first Black person to receive a graduate degree in marine science from the University of North Carolina, and now she is on track to getting her doctorate in the field.

Griffith wants to use her expertise to give back to her community and inspire other Black people not to limit their dreams.

“I’ve heard from a lot of African-American men who, when they were younger, wanted to be marine scientists and somewhere along the way, someone kind of burst a bubble,” Griffith, who completed her graduate degree in March, told Atlanta Black Star.

“So, I feel like it only makes me want to get the information out more and collaborate with different organizations to hold safe spaces where they can ask questions and feel heard and be curious about what they would potentially love,” she said.

Less than 3 percent of marine scientists are Black. Still, Griffith attributes her pursuit of a doctorate in marine science to attending Hampton University, one of two HBCUs with a marine science program. Griffith’s class of 20 students dwindled down to five by the end of the program as several of her classmates changed their focus.

Griffith found support and opportunities at Hampton that were absent from the non-HBCU she initially attended in Florida, although it was closer to the ocean. Just like her parents, the professors at Hampton nurtured her love for the field ahead.

“I honestly couldn’t have asked for a better path,” Griffith said.

Griffith now helps chart the path for Black children through her nonprofit MahoganyMermaids with swimming lessons to deeper dives into the sea, fostering their love for aquatic sciences. The mentoring and lessons have gone mostly virtual during the pandemic after launching in 2016. She connects the children with local organizations to fill the gaps.

“I think the biggest thing is providing them the groundwork and understanding that you’re welcome in this field, and that you can flourish in this field, and that you’re not alone and there’s a multitude of people who can help uplift you,” she said.

While at Hampton, Griffith was introduced to a Pathways to Ph.D. internship through UCLA. Before enlisting in the program, Griffith had never considered completing a doctorate. Through that program, she also discovered her love for working with coral reefs while doing a project in Tahiti. It led her to do her master’s thesis on the impact of hurricanes and disturbances on coral reef growth.

UNC has a specialized lab for coral reef research, and it has prepared Griffith for her next venture. Griffith is gearing up to launch a project that she hopes would improve the quality of life on the Caribbean island of Barbados, where her parents were born.

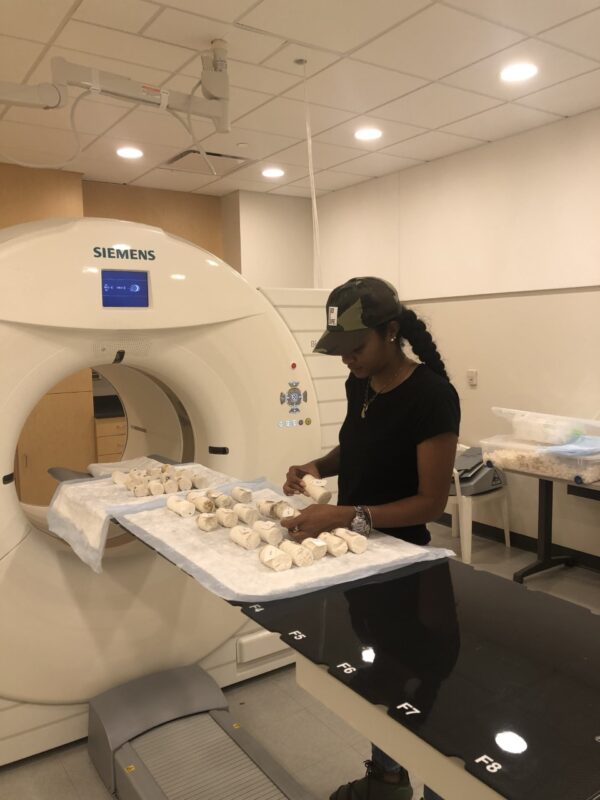

Griffith plans to introduce a new method of conducting coral reef assessments to Barbadians that would allow them to examine coral reefs more often. Coral reefs support about 35 percent of the fish in the ocean, she said. They also serve as physical barriers against storms and wave surges for coastal homes. Coral reefs play a role in medical advances as well, she said.

“Understanding how they’ve changed over time and how they might be changing due to climate change and or human stressors is really imperative on understanding what will happen to us and them in the future,” Griffith said.

Being a minority in her field has its challenges. Griffith tries not to limit herself, but there are certain states where she avoids doing research. She also finds support through the Initiative for Minority Excellence and Black Graduate and Professional Student Association at UNC. It gives her the same camaraderie that she offers children through MahoganyMermaids, connecting her with professional organizations and other Black and brown graduates.

Once Griffith obtains her doctorate, she wants to educate audiences at aquariums and museums and do more coral conservation work.

Griffith’s advice to anyone considering a career that may seem unconventional is to pursue your passion.

“Even if it’s not mainstream, it’s still important, and specifically, it’s still important to you,” she said. “So, there’s always a place for you, if you feel that that’s your passion. So, no matter what anyone else may think about it, or may feel about it if that’s definitely what you want to pursue, then there’s nothing stopping you.”