Arizona has become the first state to eliminate peremptory strikes in jury selection, after they have been used to exempt people of color from serving on juries for more than a century. The decision by the state supreme court is intended to help limit racist convictions.

“It’s a big development, it’s a change to the way civil and criminal juries have been selected in the U.S. for hundreds of years. I don’t think we really know what the implications are going to be,” Jack Chin, senior counsel and chief of the Conviction and Sentence Integrity Unit at the Pima County Attorney’s Office told KVOA.”

Peremptory strikes have long since allowed lawyers in criminal and civil trials to remove potential jurors without giving an explanation. Currently, in a criminal jury trial, 10 strikes challenges are allowed if the death penalty is on the table; and if the case is tried in superior court, six are allowed. The change to the rules was ordered on Aug. 24 and released by the court on Aug. 27. It will go into effect on Jan. 1, 2022, when only for-cause challenges will be allowed.

“When you’re picking a jury there are people who send signals, people who are not going to be favorable to your case. But this is true for both sides and both sides get to knock people off. Both sides are trying to come up with a jury that’s going to be favorable to their side,” Chin said.

Before the law goes into effect, a task force will work to recommend changes to court rules to allow potential jurors to still be removed for valid reasons, including stated bias. Some lawyers are concerned that the new measure won’t have actually produce its intended effect of reducing racist convictions through a more diverse jury, but could actually do the opposite.

“In a criminal case the government prosecutors are the ones who are discriminating against racial groups and consequently you don’t fix the problem by removing the ability of either party to exercise” a peremptory challenge, attorney Greg Kuykendall told KOVA. “In fact you may make it even worse,” he added.

“It’s a really important tool for the underdog to have,” Kuykendall said. “To be able to get rid of a juror who won’t answer the question or who is too cagey to be honest and say what they are believing.”

Although Arizona has taken more steps to end peremptory challenges, other states, including California and Washington, have also placed restrictions on the use of the strikes. The decision by Arizona’s conservative court came as a surprise to some advocates. The court’s decision came after a study published in May showed significant racial disparity in peremptory strikes.

The proposal to end the practice in Arizona was filed by two state appellate judges, Peter Swann and Paul McMurdie, who went further than advocates’ requests that restrictions like those enacted in California and Washington be adopted.

“Lawyers have practiced with peremptory strikes their entire careers, so I think there’s natural resistance to a paradigm shift in a system you’re used to. It’s like quitting smoking – it’s hard, but the fact you might enjoy smoking doesn’t mean you shouldn’t quit,” Swann told Reuters. “I’m hoping that other states will follow once they realize it can work and actually enhance the fairness of trials.

Peremptory challenges were not introduced until after the Civil War, when Black Americans began to gain more rights, including the right to serve on a jury. Since then, they’ve been used at the federal and state levels. Today, Black people are underrepresented on juries by 16 percent compared to their population nationwide.

A 1986 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Batson v. Kentucky ruling allowed the strikes to be contested if the other side suspected illegal motivations, including race, although lawyers have been able to easily avoid the test of the court. In California and Washington, restrictions on peremptory challenges make it easier to show a strike is disrciminitaory by allowing the court to consider unconscious bias rather than solely purposeful acts.

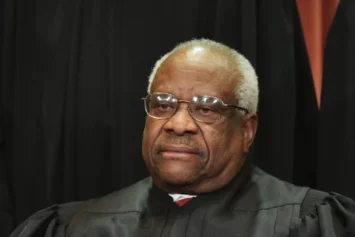

In the 1986 decision, Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote that ending racial discrimination in jury selection “can be accomplished only by eliminating peremptory challenges entirely.”