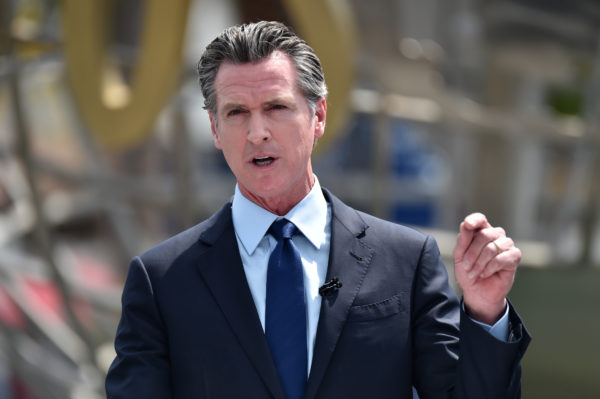

Survivors of a state-sponsored eugenics program that imposed coerced or involuntary sterilizations will receive reparations after California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill Monday night that included the long-awaited measure.

The legislation will compensate survivors sterilized under a state-sanctioned eugenics law that remained in effect from 1909 to 1979.

Newsom signed a budget deal containing The Forced or Involuntary Sterilization Compensation Program on July 12. The $7.5 million fund will also provide reparations to those forced to undergo forced sterilization in prisons after 1979.

Eugenicists used forced sterilization to “breed out” traits considered to be undesirable through procedures that often targeted minorities, the poor, those with physical disabilities, and those deemed mentally deficient, in order to prevent them from having children. The field of eugenics is now discredited, although the sterilization practice, which was carried out mostly against women, persisted in the United States for the majority of the 20th century.

By 1964, 20,108 people were sterilized in the state of California, a state that had by far the highest number of sterilizations in the United States. As many as 70,000 people were forcibly sterilized in the U.S. during the 1900s, and 32 states had some kind of federally-funded program that forcibly sterilized “undesirables.” While Black people made up 1 percent of the population California at the time, they accounted for 4 percent of sterilizations.

Nearly all of the sterilizations were performed at institutions where a patient’s consent was not required and procedures were performed on children as young as 11 years old.

Under the new measure, California will pay as many as 600 survivors $25,000 each in reparations. The measure also provides the Victim Compensation Board with $2 million for community outreach and social justice programs and the funding to track down surviving victims. Virginia and North Carolina have already begun compensating those who were forcibly sterilized.

In North Carolina, a significant portion of the people forcibly sterilized were Black women. Elaine Riddick, now 67, was raped at the age of 13, then sterilized after she gave birth to her son at 14. She was never told that she had been sterilized and did not find out until years later when she was married and trying to have children. In the paperwork, she was referred to as “feeble minded.”

“That’s a very painful thing to find out that your government allowed this to happen to you,” Riddick told The New York Times. “For them to go inside of you and wreck the inside of your body at such a young tender age. My body wasn’t even developed.”

Some see the measures as an important step towards the U.S. acknowledging its history of discriminating against people with disabilities.

“There still is a great amount of prejudice against people with disabilities and assumptions that they are, in the most extreme form, not worthy of life, not worthy of being born and certainly not worthy of parenting,” said Alexandra Minna Stern, a University of Michigan professor who is an expert on eugenics and reproductive rights.

But others say the measure comes too late. Paul A. Lombardo, a law professor at Georgia State University who has studied the eugenics movement, told The New York Times “most of the people who would have benefited are dead,” after politicians and members of the public “dragged their feet for decades” in addressing the matter.