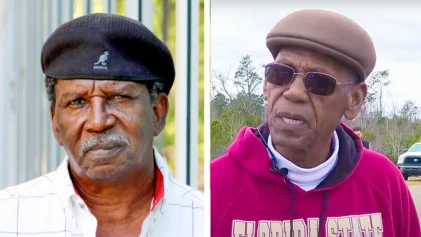

A Black man walked free in February after spending 39 years in prison for crimes he did not commit after the Georgia Innocence Project and the local district attorney asked that his convictions be vacated “as unreliable and not in the interests of justice.”

Terry Talley, now 63, was just 23 when he was arrested, and ultimately received multiple life sentences for sex crimes committed on or near LaGrange College between February and July of 1981.

Following a multi-year expansive review of the cases conducted by the LaGrange Police Department and the GIP that began in 2017, Coweta Judicial Circuit District Attorney Herb Cranford Jr. joined GIP attorney Jennifer Whitfield to file a motion to vacate four of Talley’s convictions, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

“Look where I’m at now,” Talley said outside of the Dooly State Prison upon his Feb. 23 release, The Atlanta-Journal Constitution reported. “A free man.”

The first attack took place on Feb. 7, 1981, in LaGrange, a town about 70 miles southwest of Atlanta, when a white LaGrange College student was attacked in her dormitory. The assailant choked her and put a pillowcase over her head and said, “If you tell anyone, I will kill you.” Days later, the student, who said she successfully resisted her attacker, reported the incident and identified him as a young Black man.

On Feb. 21, another white student was raped and sodomized in her dorm room. The woman was also choked and told “If you scream, I’ll kill you.” Police collected a pair of black gloves from the scene.

On Feb. 28, a student found a threating message on the windshield of her car, then received a phone call from someone she said sounded like a Black male, who told her, “I am on my way out there now.”

A 64-year-old woman was raped on April 19 inside her home about two blocks away from the location of a church where another student was choked and raped on June 24. The older woman identified her attacker as a Black man who was about 30 years old.

On June 30, a Black woman was assaulted while cleaning the Heart Clinic of the West Georgia Medical Center by a man who did not rape her because she was menstruating.

Then on July 21, an Asian woman called 911 saying she had again encountered a man she said had previously shown up to her home and attempted to offer her money for sex and enter before seeing her child and fleeing.

Police arrived and arrested the man, who was Talley. He admitted that he offered the woman money for sex and was charged with sexual battery.

Police then brought in the victims of the other attacks. The victim from April 19 identified Talley as her assailant by his voice, while the Feb. 21 victim also identified Talley. However, the victims from Feb. 7 and June 24 were unable to identify Talley.

He was charged in all attacks. At successive trials in November 1981 Talley was convicted for both the April 19 and June 24 attacks. Prosecutors did not reveal during the trial for the April 19 victim that she had a blood-alcohol level of .34 — more than four times the legal driving limit — during the attack. At the trial for the June 24 attack, the victim, who was previously unable to identify Talley in a lineup, testified that she was “positive” it was Talley had that her attacker had a “Negro smell.” Talley got sentences of life imprisonment plus 10 years for each of those cases.

Discouraged, Talley pleaded guilty to the Feb. 7 and Feb. 21 attacks and received life sentences for each. He was also sentenced to 10 years in the case of the Asian woman whose house he had gone to.

The Georgia Innocence Project took on Talley’s cases in 2008 and found through post-conviction DNA testing that he could not have been the rapist in the June 24 case. That conviction was vacated in 2013, although the indictment was not dismissed.

By 2017 the Georgia Innocence Project and the LaGrange Police Department began cooperating on a review of all of Talley’s cases. The new investigation also uncovered that a Black city employee who spent a lot of time on the campus had been the subject of complaints filed by female students alleging inappropriate conduct around the time of the attacks. The gloves found at the scene of the Feb. 21 attack appeared to be the same ones worn by the employee, but they had disappeared from the evidence by the time the new investigation was opened. The employee had not been included in any lineups. Prosecutors also violated Talley’s rights by not informing his defense about the worker, Talley’s attorneys say.

By 2020, the Georgia Innocence Project was able to hire a new investigator, when things began moving in Talley’s reopened case. The GIP found that the city employee who had been the subject of complaints around the time and place of the 1981 attacks had been suspended and fired over those complaints. Talley’s new lawyers shared their evidence with the local police and district attorney last year, and by this February police secured a warrant to obtain the DNA of the still unidentified former city worker (results of the testing are still pending). In light of the new evidence, DA Cranford joined GIP attorney Whitfield in a motion to vacate the convictions of four of the cases against him, and those charges were dismissed (Two of Talley’s convictions remain under review). Cranford also agreed not to oppose Talley’s release.

The GIP’s motion read in part: “Evidence that has come to light since Talley’s convictions now helps prove what Talley has always maintained. He is innocent of these crimes.”

“Today is such a blessing,” Talley said upon his release. “Words can’t describe how it feels to finally be free after all these years. I’m so thankful for my family, who kept me going all this time, and for the Georgia Innocence Project, who never gave up.”

GIP Executive Director Clare Gilbert spoke to the under current factors that likely influenced Talley’s conviction, “How does an innocent Black man get convicted of a series of brutally violent crimes that he did not commit? The answer lies in the power of unreliable eyewitness identification, a blinding determination by the State to convict, and systemic racial bias. Add to that an under-resourced public defender system, set in the 1980s Deep South, and you have an infallible recipe for wrongful conviction.”