In August 2019, Kimberly Diei enrolled in a graduate program at the University of Tennessee at Memphis, where she’s studying to earn her doctorate from the College of Pharmacy by 2023.

But an anonymous complaint about Diei’s Twitter and Instagram posts put those hopes in jeopardy. In September 2019, someone reported her social media activity to the pharmacy college’s Professional Conduct Committee. The committee reprimanded Diei for violating the college’s professional standards.

A year later, after receiving yet another anonymous complaint, the committee investigated Diei’s online content again. Within four days, board members voted to expel her from the pharmacy program, deeming her social media posts too “sexual,” “crude,” or “vulgar.”

Now Diei is suing UT, alleging the university infringed upon her First Amendment rights. She denies she did anything wrong and wonders why she was targeted. Diei and her legal team still have yet to learn who filed the two anonymous grievances against her.

“I look at some of my peers, and they’re able to say what they want, do what they want. So why is the attack on me?” she told Atlanta Black Star. “The whole time I’ve been in this institution, it’s just been a whole traumatic experience. I’ve been bullied, harassed for really no reason other than the fact people don’t like my personality, or don’t like that I speak up.”

The federal lawsuit claims Diei is a good student who’s been selected for “competitive internships” and had no complaints of unprofessional conduct in the classroom.

The complaint was filed Feb. 3 in U.S. District Court in western Tennessee. It lists University of Tennessee President Randy Boyd and several university administrators as defendants. Diei filed the case as a First Amendment lawsuit to stop the university from policing her “personal, off-campus expression.”

Diei earned her bachelor’s degree in biological sciences from the University of Chicago in 2015. The 27-year-old Chicagoland native enrolled at University of Tennessee’s Memphis campus in the summer of 2019, seeking a certification in nuclear pharmacy. She said she holds a 3.3 grade-point average.

She created an Instagram account under the username “KimmyKasi” in February 2016 and established a Twitter account with the same pseudonym in March 2016. Her attorneys acknowledged that Diei occasionally uses profanity on the social media sites and freely expresses her views on sexuality. But they said said she never identified herself as a University of Tennessee grad student.

“Diei perfers to maintain separation between her life as Kimberly Diei and her online expression as KimmyKasi because it allows her to more fully express herself in the public arena,” the lawsuit states.

Diei said some of her posts that allegedly violated school polices were made while the university was on summer break.

“None of these things were said in the classroom setting,” Diei said. “If I’m cursing up a storm in the middle of class, that’s unnecessary and unwarranted. But what I am talking about and how I’m speaking outside of the classroom environment, that’s really none of their business. And if someone did complain about it, the claims should have never been brought to me because I have operated well within my rights that are granted to me under the\ Constitution.”

But that distinction wasn’t enough to stop the pharmacy college’s Professional Conduct Committee from taking Diei to task over her Twitter and Instagram persona. She was first summonsed before the disciplinary board Sept. 12, 2019. Committee members unanimously agreed that her social media posts violated “various professionalism codes.” College of Pharmacy Dean Marie Chisolm-Burns told Diei to write a letter “reflecting on her behavior” in October 2019, the lawsuit said.

But Diei said the board never specified exactly how the posts were too crude and sexual in nature. She was “extremely distressed” by the decision but agreed to write the letter to preserve her slot in the graduate program.

Greg Greubel, one of the attorneys who is representing Diei pro bono, argued that the college’s professionalism standards are too vague and subjective, and they are not clearly outlined when it comes to social media.

The suit claims an error message popped up on the school’s web page for “Standards for Student Professionalism Conduct.” When Atlanta Black Star accessed the page last week, it appeared to be blank.

“The university really made no effort, from my perspective, to try and try and show us the policy, or try and even give us a better understanding of what this policy says what it prohibits,” he said Tuesday. “So we were left to guess, unfortunately.”

Greubel works for Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, a Philadelphia-based nonprofit group that focuses on First Amendment rights of students.

He explained that the free-speech protections apply in this case because the University of Tennessee is a public institution, as opposed to a private company that has much broader latitudes in monitoring employees’ social media profiles.

“I think the problem here stems from a lack of understanding more about Black culture and the kind of discussions that she was engaging in,” he said. “They’re not outside of the realm of normal discussions for any culture on on the internet, really. Anybody that has spent time looking through Twitter, this is what people talk about.”

Diei was “extremely distressed” by decision but agreed to write the letter to preserve her slot in the graduate program. The lawsuit, she didn’t admit to violating the professional standards but said she

In her 2019 letter, Diei told committee members she’d use her “best guess” to adhere to social media standards, although she admitted she didn’t understand how she violated the school’s policies in the first place.

She said she spent more than 10 months self-censoring herself online. Then on Aug. 27, the second anonymous complaint surfaced. This time, Dr. Christa George, the committee’s chairwoman, provided screenshots of three profanity-laced Twitter posts in which Diei shared photos of herself or made sexual commentary. Once again, school officials deemed them unprofessional.

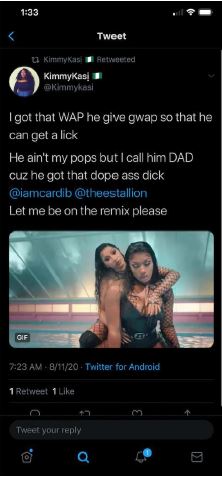

Two of the posts centered on the song “WAP.” The Cardi B/Megan Thee Stallion collaboration topped the Billboard charts last year and lit Twitter up with debates about whether the sexually explicit single and its accompanying music video crossed the line.

“I got that WAP he give me gwap so that he can get a lick,” Diei wrote, parodying the suggestive lyrics in an Aug. 11 tweet. “He ain’t my pop but I call him DAD cuz he got that dope a– d–k.”

Diei tagged Cardi and Megan and joked that she wanted to be on the rap star’s remix of the song. She defended the raunchy anthem in another tweet:

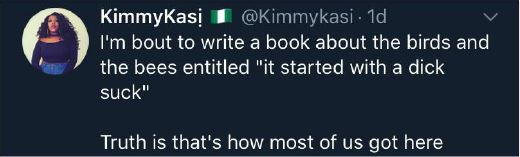

“I’m bout to write a book about the birds and the bees entitled ‘it started with a d–k suck.’ Truth is that’s how most of us got here.”

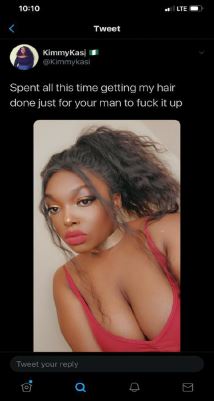

In a third tweet, Diei shared a photo of herself in a lowcut top and joked about how long it took her to get gussied up.

“Spent all this time getting my hair done just for your man to f–k it up.”

George said the posts were objectionable but gave no specifics as to why, the lawsuit claims. Diei said when she asked school officials what policies she violated, they told her they’d explain during a board inquiry.

Diei appeared before the committee panel for a second time Sept. 1. The following day, George sent Diei an email informing her of the board’s unanimous decision to expel her for “serious breach of the norms and expectations of the professions.”

Diei appealed the decision to Chisolm-Burns on Sept. 4 and her lawyers also sent the dean a letter advocating for a reversal, calling the decision unconstitutional. Diei and Chisolm-Burns spoke several times over the next few weeks, with Diei making her case to be reinstated in the grad program. The dean finally relented and overturned Diei’s expulsion on Sept. 25.

Diei said school officials never explained her alleged policy violations to her. She believes her bustier body type factored into the university’s reaction to many of her online selfies.

“It’s extremely frustrating, and I do believe race plays a factor,” she said. “Because I am a darker skinned, Black American woman. Growing up, we’re automatically as Black women sexualized. But then when we finally grow into our own and seek to embrace our sexuality, that’s when it’s a problem. And we’re told we can’t do that as if we should be ashamed of how we look. But if a white person is to then pull from our natural born aesthetics, then it’s high fashion and it’s beautiful.”

Despite the reversal, Diei said she still lives in fear of another committee investigation. She worries that could put her doctoral degree at risk.

The Professional Conduct Committee is a 12-member panel that includes three students, according to Greubel. Diei noted that all of the faculty members on the committee were older, white professors and university administrators. She and said one of the student board members was a classmate who had previously ridiculed her online.

“So what they’re going to see as inappropriate and unprofessional, truly isn’t,” Diei said. “It’s just they’re not used to seeing it, they don’t understand it. And therefore, anything that they don’t understand, they’re going to be leery of.

“Because I haven’t said or done anything that no one else is out there doing. I’m just not afraid to say what I have to say,” she added. “They’re just not understanding how students of my age in this generation and in my culture talk to one another. They just don’t get it.”

Diei’s lawsuit alleges that the arbitrary and subjective way University of Tennessee officials levied the professionalism policy violated her First and Fourteenth Amendment rights and undermined her free speech rights. The suit seeks a judgment declaring the vague rules unconstitutional as well as a permanent injunction to restrain the university from enforcing such vague policies again.

“Sex Week,” an annual spring event on University of Tennessee’s Knoxville campus, served as a lighting rod of controversy for years, according to the Tennessean. Conservative lawmakers in the state routinely took aim at the six-day event and sought to shut it down, calling it a showcasing of debauchery and a “national embarrassment.” Sex Week began in 2013, organized by a student group as a variety of sex-related events and panel discussions on sexuality and gender. Following a special report from Tennessee’s comptroller in February 2019, the university made a policy change and stopped allocating state funding for events organized by student organizations.

“We want to be perfectly clear, the University of Tennessee does not condone or support the sensational and explicit programming that Sex Week has often provided,” University President Randy Boyd said in a statement at the time. “We believe it has damaged the reputation and overshadowed the many achievements of our university with the people of Tennessee, with the legislature that represent them, with the over 382,000 alumni worldwide and 220,000 alumni in Tennessee and is not representative of the vast majority of our students.”

Foundation for Individual Rights in Education’s work to subdue online censorship dates back to 2006. One of the organization’s earliest cases came in 2007, when Valdosta State University student Hayden Barnes was expelled. The student sent emails, posted flyers and took to Facebook to criticize the university’s plan to use $30 million in student activity fees to build an on-campus parking garage. Barnes also criticized the university’s president Ronald Zaccari, who called him a “clear and present danger” to the campus and pushed for his dismissal. Barnes eventually won a $900,000 settlement from the university.

Greubel said he represented a student last year who was booted from medical school for making parodies of rap songs. He said the free speech violations are particularly rampant in graduate and post-graduate programs.

“I have observed over the past couple years working here that students do get punished under these vague professionalism policies and other policies that have very old-timey words like decorum,” Greubel said. “Universities use these type of policies to punish students for speech that they simply don’t like, or don’t agree with, or they don’t understand. And I think that this is sort of a case of lack of understanding, and a lack of willingness to be open to different ways of living.”