Susan Moore’s ordeal began on Nov. 29 when she tested positive for COVID-19 and was admitted to IU Health North Hospital in Carmel, Indiana.

She had a fever of 101.5, a critically low respiratory rate in the 30s and her heart rate hovered above 150. All signs she had a severe case of the deadly virus that was arresting her lungs.

But Moore, a Black physician, was denied adequate care when she reached her hospital room, according to an impassioned self-recording that she posted on her Facebook page.

The 52-year-old Indianapolis internist complained that her white doctor tried to send her home while the virus was still spreading in her body, and he refused to prescribe her medication despite the fact she was in “intense pain.” She said the physician, whom she identified as Dr. Eric Bannec, told her he didn’t “feel comfortable” giving her narcotics and never physically treated her.

“I was in so much pain. My neck hurt so bad,” Moore said in the Dec. 4 video, which she recorded from her hospital bed. “I was crushed. He made me feel like I was a drug addict, and he knew I was a physician.”

Moore spoke through anguished tears and labored breaths. She was feeble and clearly weakened. Despite the unmistakable toll the virus had taken on her health, she seethed at the treatment she received from nurses and doctors at IU Health.

“You have to show proof that you have something wrong with you in order for you to get the medicine,” she fumed. “I put forth and I maintain if I was white, I wouldn’t have to go through that.”

Dennis Murphy, IU Health’s President and CEO, described Moore’s death as “doubly distressing” in a Dec. 24 statement, noting that she was a “distressed patient who was a member of our own profession.” He called for an external medical review from a panel of healthcare and diversity experts to root out any bias in Moore’s treatment.

“I do not believe that we failed the technical aspects of the delivery of Dr. Moore’s care,” Murphy said in the statement. “I am concerned, however, that we may not have shown the level of compassion and respect we strive for in understanding what matters most to patients. I am worried that our care team did not have the time due to the burden of this pandemic to hear and understand patient concerns and questions.”

The 7 1/2-minute video proved to be one of Moore’s final pleas. She succumbed to her bout with COVID-19 on Dec. 20, less than two weeks after she was discharged from the IU hospital.

But for four days, she continued to update the Facebook post that accompanied her Dec. 4 video. She used the post to publicly chronicle her care, documenting everything from the rounds of Remdesivir treatment she received to the volley of X-ray tests she underwent.

She listed her daily oxygen and blood pressure levels. At one point, Moore said she began coughing up blood, forcing pulmonologists to boost her steroid treatments.

In the week since news of her death, Moore’s 7 1/2-minute video has spread quickly across social media, sparking debates about the implicit biases in the health care system and how those can lead to disparities in the medical treatment Black patients are afforded.

Speaking with an oxygen tube hooked up to her nose, Moore said Dr. Bannec tried to send her home the previous day, although she’d only received two rounds of Remdesivir, the antiviral drug used to treat hospitalized COVID patients whose condition is not critical enough to warrant a mechanical ventilator.

She said Bannec told her she didn’t need the drug and claimed she wasn’t short of breath. But during her video, Moore took long pauses to gather her wind while talking. She said the doctor told her she didn’t qualify for Remdesivir, despite the fact she’d already received two rounds, and suggested she be discharged.

“You should just go home right now, and I don’t feel comfortable giving you any more narcotics” Bannec said, according to Moore.

But Moore said she reached out to a patient advocate because of the severe pain in her neck. Moore demanded to be transferred.

“If you’re not going to treat me here properly, send me to another hospital,” she said.

Soon afterward, a CT scan was done on Moore’s neck, both with and without contrast. She said the tests showed pulmonary infiltrates in her lungs, a sign of pneumonia, and new lymphadenopathy throughout her neck. That disease commonly produces inflamed or enlarged lymph nodes.

That’s when doctors finally agreed to treat her with pain medication, she said. But even then, she had to wait.

Moore recounted how a nurse took nealry three hours to deliver her meds after Dr. Bannec finally prescribed Percocet to relieve her pain. She said a white male nurse snapped at her when she confronted him about it.

“You’re not my only patient, I have five other patients, you know,” the nurse said, according to her video.

“I have been in pain since 7 a.m., you know,” Moore shot back.

“Well I can’t be in here every five minutes,” the nurse responded, she said.

The two went back and forth, and Moore said she told the nurse, “I am a patient, are you going to take care of me or not?”

At some point, Moore said she spoke to the hospital’s chief medical officer and pulmonologists adjusted her care plan. Her fever subsided, her blood pressure and heart rate stabilized, and she was taken off oxygen. She said she was receiving “very compassionate care” in one of her final updates.

But Moore said Dr. Bannec tried to have her released from the hospital at 10 p.m. on Dec. 5, a Saturday night. She noted it’s not common to discharge a patient at such a weekend hour.

“That is not how you treat patients. Period,” Moore said. “So I don’t trust this hospital, and I’m asking to be transferred. These people wanted to send me home with new pulmonary infiltrates and all kind of lymphadenopathy in my neck.”

Moore was finally discharged Dec. 7, according to the Indianapolis Star. Her fever spiked to 103, her blood pressure plummeted and her heart rate skyrocketed to 132 less than 12 hours after she returned home. She was re-admitted to a different hospital, Ascencion-Saint Vincent in Caramel, Indiana.

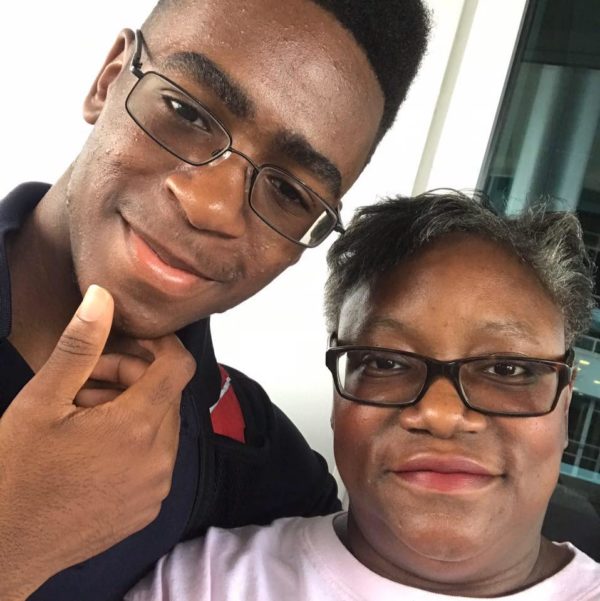

By Dec. 18, her health had deteriorated to the point that she was 100 percent reliant on a ventilator to breathe, her 19-year-old son Henry Muhammed told the New York Times. Muhammed said he visited Moore in the hospital before she died two days later and told his mother not to worry about him.

“If you want to fight, now is the time to fight,” he said to his dying mother. “But if you need to go, I understand.”

A GoFundMe page was set up to assist Muhammed and Moore’s parents, both of whom suffer from dementia. The account had raised nearly $170,000 by Monday afternoon.

“Susan was a phenomenal doctor,” Moore was lamented on the the page. “She loved practicing medicine, she loved being a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc, she loved helping people, and she was unapologetic about it.”