Sunken relics plummet to the ocean floor and are often forgotten for eternity.

Occasionally, some resurface, even after thousands of years. And once rediscovered, they harken back to a time long lost.

That holds true even for the horrors of mankind.

The trenches of the Atlantic Ocean are seeded with the anguished souls of countless kidnapped Africans who died during the Middle Passage.

The trans-Atlantic slave trade spanned from the 14th to the 19th centuries. Nearly 13 million bought or captured mostly West African captives were crammed into the hulls of ships as cargo and transported across continents for profit.

An estimated 2 million died during the unforgiving voyage, according to historical assessments. Most were tossed overboard afterward, turning the ocean floor into a burial ground.

But enslaved transports weren’t the only casualties.

An estimated 1,000 vessels reportedly shipwrecked while traversing the Atlantic, according to the Slave Wrecks Project, a study of sunken slave ships featured at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture.

Only a handful of the embattled slavery ships have been found. A team of marine archaeologists plans to change that.

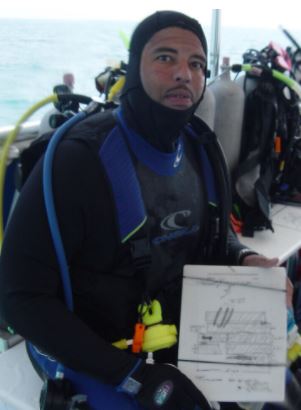

Volunteers from Diving With a Purpose have spent the past 16 years plunging to mine for the ruins of sunken slave ships. Their mission is to preserve history and document the “submerged heritage” lost in the waters.

Diving With a Purpose co-founder Ken Stewart has participated in a number of searches, including dives for the Henrietta Marie, the first slave ship ever raised from the water. He understands the spiritual awakening many people go through on the missions.

“It’s just an eerie and strange feeling,” Stewart told the Atlanta Black Star. “Sometimes you can feel the souls of your ancestors tugging on you saying this is why we went down. So it’s just a true feeling of spritualness, I guess.”

DWP is a volunteer underwater archaeology program with more than 500 divers. According to its website, the nonprofit focuses on education and training programs that foster underwater conservation. Its motto is “restoring our oceans, preserving our heritage.”

Through its early years, DWP was a predominantly Black organization. But Stewart said the volunteer group has grown and now boasts a diverse array of scuba divers.

The team of volunteers train youth and young adult divers each year in the Florida Keys. They also teach diving classes in Mozambique and off the coast of South Africa. DWP divers have even scoured the Great Lakes for remnants of crashed World War II fighter planes flown by Tuskegee Airmen.

DWP has helped salvage 18 shipwrecks and logged thousands of volunteer hours, working on projects across the globe that explore the African diaspora. One of its core missions is combing ocean floors for the remains of wrecked slave ships to document and study the African slave trade.

“We need to do this ourselves,” Alberto Jose Jones said during a recent forum. “We can’t expect somebody else to go out and find our history. So we need to get people trained to go out and do it ourselves.”

The Museums of Science & Culture at Harvard University hosted an Oct. 22 virtual panel discussion featuring four of DWP’s leading members. Jones, an International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame inductee who now serves as a director of DWP, was one of four panelists who spoke during the summit. He was joined by fellow DWP veterans Jay Haigler, Erik Denson and Ayana Omilade Flewellen.

Haigler, a master scuba diver, said such public events raise awareness for maritime archaeology and ocean conservation.

“Everything that we do involves kind of an ancestral part, but it also involves that ancestry touching today,” Haigler said. “Ocean conservation is really about bringing the ocean back to what it was. Those are the things that really are important and is the foundation for our future.”

‘Let’s dive with a purpose’

Diving With a Purpose is an idea that started with a phone call in 2003. PBS was producing an episode for its documentary series “Changing Seas.” The episode chronicled the search for the Guerrero, a Spanish slave ship that has eluded researchers for decades.

The Guerrero was just as fleeting when it sailed the ocean as an outlawed slave vessel. Its luck ran its course in December 1827, when the ship, en route from Africa to Cuba with captured Africans aboard, ran aground on a reef and sank in the Florida Keys. Forty-one of 561 Africans on board drowned as the hull was breached. The ship went down as it was being pursued by a British naval vessel policing the waters and enforcing the British ban on the importation of captured Africans to Cuba for slavery, a ban which was routinely flouted at the time. When the surviving captives and crew of the Guerrero were loaded aboard several salvage ships over the following days, the Spanish slavers were able to hijack two of ships and make their escape to Cuba, where they sold hundreds of those Africans into bondage.

A producer of the “Changing Seas” episode reached out to Stewart, a leading member of the National Association of Black Scuba Divers, and asked for his help enlisting Black divers to be interviewed.

While working on the series, Stewart struck up a relationship with Brenda Lazendorf, who was the star of the documentary.

Lazendorf was the lone marine archaeologist at Biscayne National Park, a 173,000-acre marine park that is the largest in the National Parks system.

Choppy tides and shallow sea beds make the Florida Keys a vulnerable spot for ships. The waters, accordingly, are littered with a trail of over 40 historic shipwrecks. Lazendorf was the only person documenting the sunken vessels and asked for Stewart’s help mapping the shipwrecks, identifying the artifacts and documenting the finds.

Stewart agreed and began recruiting his brethren with a singular pitch: “Tired of the same old dives? Let’s dive with a purpose!”

Erik Denson, a chief engineer at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, was one of the first divers to take Stewart up on his offer. He remains sixteen years later, and is one of DWP’s board members and a lead instructor.

“Telling this story is most profound, and that makes it spiritual to me,” he said. “Especially when it comes to contributions of African Americans and maritime history and culture. It is important to share this rich history with generations to come.”

From the seas to the skies

One of Diving With a Purpose’s special missions is a project to memorialize the Tuskegee Airmen. The famed Black aviators did advanced training in Michigan after leaving basic flight school in Tuskegee, Alabama. Fourteen Red Tails went down in training accidents during the advanced training and five of them crashed in the Great Lakes.

One of those crashes in April 1941 was a P-39 Airacobra plane flown by 2nd Lt. Frank H. Moody. The wreckage wasn’t discovered until April 11, 2014 — exactly 73 years later — when DWP teamed with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to salvage fragments from the crash.

DWP will unveil a memorial to the 14 Tuskegee Airmen who died in training accidents during a ceremony planned for Aug. 28, 2021, in Port Huron, Michigan.

In addition to salvaging Tuskegee Airman aircraft, the volunteer group has collaborated with Biscayne National Park to document shipwrecks near the Florida Keys since inception.

Stewart said his team will conduct a third search for the Guerrero next year, planning to focus on the southern part of the park.

Outside of mining for underwater relics, DWP’s other primary mission is training. Its flagship is a weeklong maritime archaeology training program that teaches veteran divers the basics of underwater research and oceanography. More than 300 divers have taken the course.

DWP also boasts a coral ecosystem restoration program. One of its crowning achievements is a youth program launched in 2012 that teaches underwater archaeology to divers aged 15-23.

Finding purpose underwater

DWP’s partnered with several organizations for the Slave Wrecks Project, which led to the first discovery of a ship that sank while slaves were on board. The São José Paquete Africa, a Portuguese vessel, was bound from Mozambique to Brazil with a cargo of captured Africans when it hit two coral reefs and ran aground off the coast of what is now Cape Town, South Africa, on Dec. 27, 1794. A total of 543 shackled Africans were aboard when the ship capsized. About 330 of them survived, according to historians.

DWP was part of a team of researches that recovered shackles, barrels and pieces of the São José Paquete Africa from the seafloor off Cape Town 2015. The artifacts, which provide a candid peek into the conditions of the slave trade, are now part of an exhibit at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

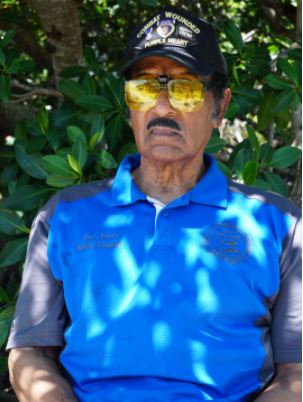

Jones co-founded the National Association of Black Scuba Divers. The Purple Heart recipient has enjoyed a decorated 37-year career as a marine biologist and environmental scientist. He is regarded as the father of modern scuba diving.

Jones has participated in thousands of dives around the world, but he said the emotions of salvaging slave ships can be overwhelming.

“I’ve seen grown men — big 250-pound guys with a bunch of muscles — tough guys break down and cry. Especially when we find something like the shackles that were made for children,” he said. “This is a lot different. This is more than just fun and going down taking pictures. This has to do with digging up history, filling in the gaps. I’ve had the opportunity to see artifacts that have come up from the slave wrecks. I had the chance to go out and dive the wrecks. And it was not like any other dive. It was like touching the souls of your ancestors.”

Raising awareness

DWP’s conquests have been showcased by National Geographic. It has an exhibit in the History of Diving Museum in South Florida.

Flewellen is an anthropology professor at University of California-Riverside who co-founded the Society of Black Archaeologists. She’s one of the DWP board’s newest directors and said the organization’s presence is especially significant, given the fact that less than 1 percent of the world’s archaeologists are of African descent.

Flewellen contends DWP is breaking barriers and helping to de-colonize a field that Black people have traditionally been shut out of or had little access to.

“The work that we are doing is absolutely transformative on so many different levels,” she said. “It is really providing the space outside of academia that challenges the representation of what archaeology is, who can be an archaeologist and how that person looks.”

DWP is also a main focus of “Enslaved,” a six-part docuseries hosted and executive produced by Oscar-nominated actor Samuel L. Jackson. The series follows Jackson as he traces his African roots against the backdrop of DWP’s search for the Guerrero and other slave vessels.

The series, which premiered on the Epix channel in September, also offers a thorough examination of the 400 years of human trafficking from Africa to the New World and uses marine archaeologists to illustrate rarely told stories from the Middle Passage.

“The global slave trade is an extremely complicated story, and it demands the attention of people who have the hearts and minds to tell that story well,” Haigler said. “Now this documentary series has the power to take that story to a huge audience. It also can help bring attention to the work of professional marine archaeologists who have been active in marine research for decades.

“It is important to understand that there is that connection from the sea to the land and our ancestors from the past to the present,” he added.