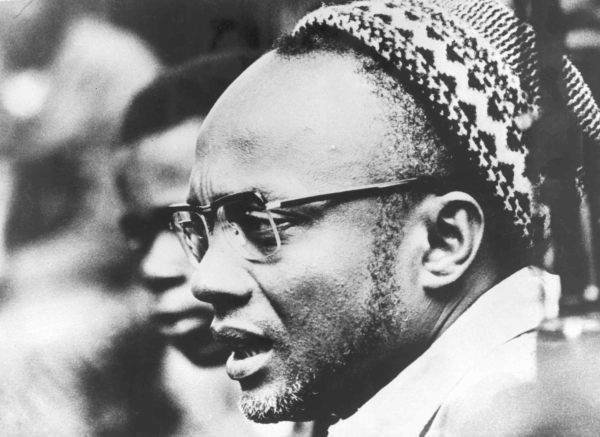

Although he was assassinated more than 45 years ago, the spirit of Amilcar Cabral lives on, and his philosophy, activism and actions for the sake of African liberation resonate today. The Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verdean engineer, socialist, revolutionary and anti-colonialist led the armed struggle against Portuguese colonial rule in Africa, helping to dismantle the fascist European empire during the Cold War.

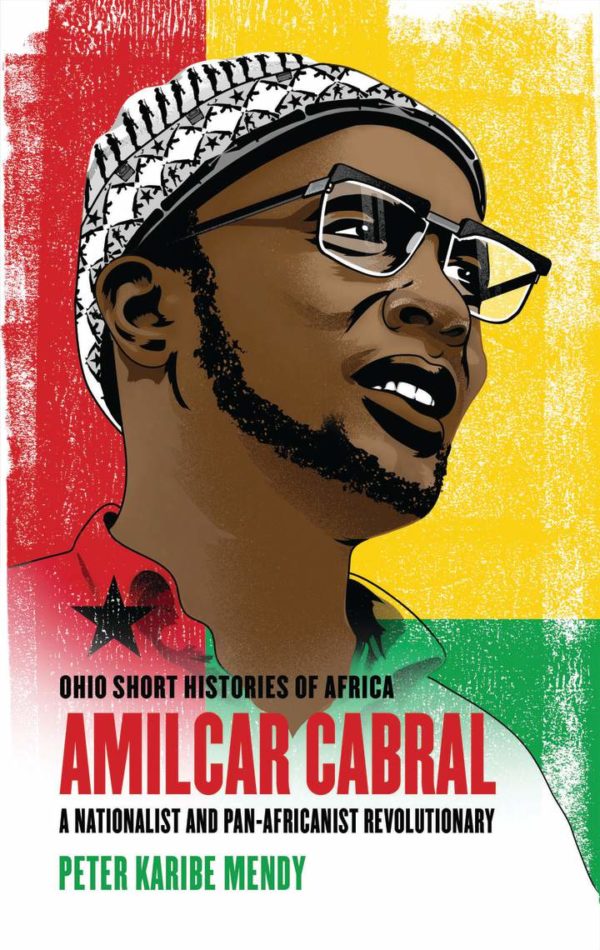

A new book sheds light on Cabral and his legacy. Peter Karibe Mendy, professor of history and Africana studies at Rhode Island College, is the author of the book “Amílcar Cabral: Nationalist and Pan-Africanist Revolutionary,” published by Ohio University Press. According to Mendy, Cabral the agronomist, the nationalist, pan-Africanist and internationalist was among “Africa’s most original thinkers and politically influential figures” of the past century.

This latest biography on Cabral is timely one, as resistance movements erupt around the world, and people of African descent continue to grapple with oppression, injustice and exploitation. “An engaged intellectual and revolutionary, he wrote innovative works on liberation theory and practice, culture, African history, and class formation, and his powerful ideas still resonate today,” Mendy told Atlanta Black Star regarding Cabral.

While studying in Lisbon, Portugal, in the 1940s, Cabral interacted with African nationalists and Portuguese anti-fascists. He connected with fellow students such as Brazilian poet Mario de Andrade, Mozambican poet and revolutionary Marcelino dos Santos, and first Angolan president Agostinho Neto, and helped to form an association of Lusophone African students called the Centro de Estudos Africanos. When he returned to Africa, he founded Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC), the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde, and co-founded Movimento Popular Libertação de Angola (MPLA), the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola.

A Marxian thinker who was reluctant to call himself a Marxist, as Mendy noted in his book, Cabral’s treatment of socialism was grounded in the socioeconomic realities of the Third World. Cabral advocated for restoring the “indigenous integrity” of colonized people, and the decolonization of Marxism and its European-centered focus strictly on history in terms of class struggle. In his view, Marxism had to expand its view in order to be relevant to colonial systems of oppression. Cabral maintained that colonial and imperial powers exerted cultural domination over indigenous populations through organized repression, as was the case of apartheid South Africa. Where the indigenous culture is strong, he posited, this domination cannot be permanent.

According to Cabral, national liberation and resistance to foreign domination are an act of culture. In a 1970 speech at Syracuse University, Cabral noted that colonizers not only create systems to culturally repress the colonized, but also divide or deepen divisions in a colonized society. The colonizer “provokes and develops the cultural alienation of a part of the population, either by so-called assimilation of indigenous people, or by creating a social gap between the indigenous elites and the popular masses.” Through this process, he argued, “a considerable part of the population, notably the urban or peasant petite bourgeoisie, assimilates the colonizer’s mentality, considers itself culturally superior to its own people and ignores or looks down upon their cultural values.” Therefore, concerned that systems of class oppression threaten to continue even after the colonizers leave, Cabral called for a reconversion of minds and mindset — re-Africanization — to enable a true integration of people into a liberation movement.

In addition, Cabral urged that the leadership of independence movements must commit “class suicide,” lest they become a small elite and privileged class perpetuating neo-colonial policies. Some would point to former South African President Thabo Mbeki of the African National Congress and his neoliberal economic policies — which benefited Black elites and the white power structure that ruled under apartheid — as a case in point.

Under the leadership of the PAIGC, Cabral envisioned the liberation of Portugal’s African colonies and a free Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. Further, he established military training camps in Ghana with the support of Kwame Nkrumah, and his liberation movement received aid and assistance from Cuba, the Soviet Union, China and other communist countries.

Cabral opposed “gratuitous violence,” and like the revolutionary writer Frantz Fanon, was a peace-oriented man who sought nonviolent protest, strikes and demonstrations before opting for revolutionary channels. Violence was a last resort, and Portuguese colonialism radicalized Cabral. Further, Cabral viewed African revolution and revolution for all colonized people as not merely a fight for ideas of freedom, but also for tangible improvements in the everyday lives of people.

“He was a charismatic and visionary leader who led of one of Africa’s most exemplary and consequential anti-colonial struggles that militarily defeated, with a guerrilla force of less than ten thousand men, a 40,000-strong colonial army with monopoly of air power and the use of napalm bombs, liberating not only the people of Guinea-Bissau and Cabo Verde but triggering a chain of events that led to the downfall of the 48-year old fascist dictatorship in Portugal and the dismantlement the Portuguese empire in Africa,” Mendy said. Cabral influenced not only Portuguese antifascist revolutionaries, but also the Portuguese soldiers who fought against and were captured by the PAIGC. Some of the officers who participated in the overthrow of the fascist government in Lisbon through the Portuguese leftist Armed Forces Movement (MFA) had been stationed in Guinea-Bissau.

Despite the odds, Cabral’s vision was realized, even as he was not alive to witness the fruits of his labor and struggle. Cabral was assassinated in 1973 by PAIGC member Inocêncio Kani, who was believed to have been working with agents of the Portuguese colonizer. The following year saw the overthrow of Portugal’s fascist dictatorship — known as the Estado Novo or New State — and the unraveling of its colonial empire.

Not only a pan-Africanist and a socialist but also an internationalist, Cabral was unwavering in speaking out against political and social injustices and showed solidarity “with every just cause in the world,” Mendy noted. “His solidarity with the civil and political struggles of African Americans was clearly expressed in the aftermath of the Watts Rebellion in August 1965, when he emphatically stated: ‘We are with the blacks of the United States of America, we are with them in the streets of Los Angeles, and when they are deprived of all possibility of life, we suffer with them,’” the author added.

In his last visit to the U.S. and his second address to the United Nations General Assembly in 1972, Amilcar Cabral linked the international obligation to end Portuguese colonial domination in Africa with the commitment to end such domination everywhere, with a view to facilitating liberation for all colonized peoples.

The impact of Cabral’s philosophy has extended throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America, to liberation struggles in South Africa, Angola, Mozambique and elsewhere. Cabral had a great influence on the pro-independence movement in East Timor, a Portuguese colony subsequently occupied by Indonesia before gaining independence, and whose people are of Melanesian and Malay-Polynesian descent. East Timor, like the Portuguese colonies in Africa, was underdeveloped and had a small class of assimilated, Westernized and educated elites. José Ramos Horta, leader of the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor, or Fretilin, called Cabral “the great African thinker and revolutionary leader of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde.”

The heirs to Cabral and his school of liberation through cultural identity are found in the new Black activism and identity politics of Latin America and the Black indigenous movements of people such as the Garifuna in Honduras. Others examples are the Black indigenous anti-colonial movement in West Papua, and Melanesian cultural nationalism that is deeply influenced by Pan-Africanism, Black Power and other Black diasporic movements.

Mendy believes Cabral’s calls for the “mental decolonization” and “total liberation of Africa” are relevant in today’s reality, given the “daily struggles of millions of peoples in the world against oppression and exploitation, poverty and underdevelopment, racism, sexism, and the denial of fundamental rights and freedoms.”