Nearly a week after a Texas woman was shot and killed inside her Fort Worth home, activists are speaking out against the fact that many officers who fatally shoot individuals are usually not questioned for up to several weeks.

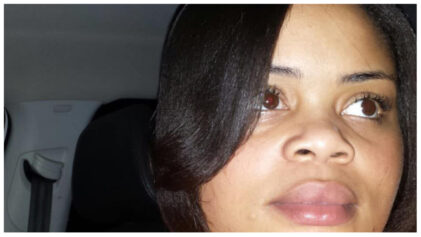

In the case of Atatiana Jefferson, former Fort Worth police officer Aaron Dean resigned after he shot through her window mere seconds after shouting, “Put your hands up — show me your hands!”

“He resigned before his opportunity to be cooperative,” Interim Police Chief Ed Kraus said at a press conference earlier this week of Dean’s resignation. Dean shot and killed Jefferson Saturday and resigned on Monday. He was arrested and charged with murder for the deadly shooting and released on $200,000 bond.

Meanwhile, lawyers for Dean have promised to provide a written statement from their client, but that has yet to materialize.

It’s the newest example of police officers fatally shooting people remaining silent in the wake of the incident. The Associated Press reports the period of keeping quiet is often outlined in state law, deemed Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights, or it is dictated in the police department’s contract. Under these guidelines, officers can take anywhere from up to 24 hours to two weeks to give a statement on what happened from their perspective.

Experts and those within law enforcement say police need time to gather their thoughts without giving details marred by the shock of the shooting.

But that’s not the way activists see it. They say it gives them time to polish up their stories. That’s the take Bob Bennett, an attorney in Minnesota who represented the family of Justine Ruszczyk Damond. The unarmed woman was shot and killed by officer Mohamed Noor in 2017 when she called 911 to report a possible sexual assault.

“Why are police, who are professionally trained to observe, to record material, to accurately and completely record all the material and facts of an incident, why are they excused from rendering their report and statement in the same timeframe as untrained, unprofessional witnesses are?” Bennett told the AP.

Meanwhile, those tied to law enforcement say there are psychological tolls that come with fatally shooting individuals.

“Of course the critics and the people who don’t trust the police say, ‘Yeah, they need time to get their story together,'” Tom Manger, a retired police chief in Virginia and Maryland said to the wire service. “Having some time to calm down and get your thoughts together … oftentimes, you get clearer answers and better information.”

There have been talks of reforms for this so-called cooling-off period. In Dallas this past January, police Chief U. Renee Hall advocated for doing away with the city’s 72-hour period in which police are not compelled to be interrogated.

However, for Dallas Observer columnist Jim Schutze, getting rid of that won’t solve the problem.

“What worries me is the assertion that doing away with the 72-hour cooling off period will put cops and citizens on an equal footing,” he wrote.

“No citizen of the United States can be compelled to give evidence against himself, unless the judge wants to give him immunity or cite him for contempt,” he said in a hypothetical explanation of how he feels things should go. “When I was asking a criminal attorney friend of mine about this years ago, he told me if I ever found myself in a dicey position, like I thought I was shooting a burglar but I shot my neighbor instead, I should shut up until he got there.”

Additionally, a study published in the Washington Post found that “cooling off” periods do not help officers recall the events that occurred in incidents where they shoot suspects or unarmed people.