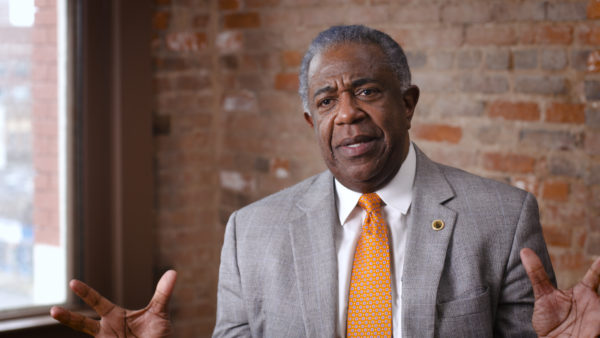

When Larry Thornton became one of six students to integrate Goodwyn Middle School in 1967, he was hardly a star student.

He said he couldn’t even imagine the man he would some day become.

The self-made author and entrepreneur went from making $5 an hour painting signs at Coca-Cola to becoming the first Black owner of a McDonald’s franchise in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1992.

He also became the first Black member of the board of directors for Coca-Cola’s Bottling Company United, Inc. in 2003.

Now, his book, “Why Not Win?” has informed the curriculum for a nonprofit institute aimed at preparing students, industry executives and employees to succeed in leadership roles, Zillah Fluker, a spokeswoman for the Why Not Win institute, said.

The institute has used the book’s revenue to fund its programming and to donate $3,000 to the UNCF (United Negro College Fund) and almost $1,000 to the Tom Joyner Foundation for scholarships.

It’s the kind of success Thornton said in a recent phone interview with Atlanta Black Star that he didn’t think was possible as a boy.

He was a child during a time when it was normal for his mom to warn him:

“Watch out for the chain gang. Watch out for the Klan.”

He still remembers receiving the news on April 4, 1968, that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been killed. Thornton was 12 years old.

He said coming to school the next day was tough, but he remembers exiting the school bus and seeing a crowd unlike any other day. The mass of parents and onlookers were waiting to see how the six Black kids responded to King’s death.

Thornton said he remembers dead silence until a freckle-faced, white boy broke that silence.

“Y’alls king is dead,” he said. “What y’all n—-s gon do now?”

Thornton said that was the last straw.

“I just retreated into my art, into my drawing,” he said.

He wrote off school, mostly because school had written him off.

“There was a certain element of suppose about it all that I never could figure out in my young mind,” Thornton said.

A Black boy at a predominantly white school, he wasn’t supposed to be treated fairly. He wasn’t supposed to be smart.

White students avoided him in the hallways. They refused to drink from a water fountain after he used it. And if he ever got the ball playing football, he wouldn’t have to worry about being able to score touchdowns because the white players didn’t want to touch him.

“Because of my skin pigment and hair texture, this is life,” Thornton said he thought at the time.

He failed summer school twice, once after ninth grade before he was passed on to 10th anyway and again after 10th grade before he was passed on to the 11th.

The next year is when he found out through luck of the draw, he had gotten the English teacher all the students at school tried to avoid.

She was a World War II veteran Thornton simply knew as Miss Nichols.

“This lady was just hard core,” Thornton said.

Tough as she may have been, she was also fair, which Thornton learned when she assigned a book report on “The Pilgrim’s Progress” by author John Bunyan.

Having picked up on the telling names of some of the story’s characters, Thornton got a B+ on the report, and that earned him an invitation inside the woman’s home.

Thornton and his dad, a baker who couldn’t read, would pick up extra cash doing yard work for white people in his community. That included Miss Nichols.

But rather than paper cup of water and sandwich brought out back to the boy, Thornton remembers Miss Nichols inviting him in, and he learned that the unrelenting woman he knew at school was actually kind and warm.

“She said to me, ‘I think you ought to go to college,” Thornton said. “That’s the first time that college ever entered my mind.”

He said that’s also the first time his name and college were even mentioned in the same sentence, but he trusted Miss Nichols to tell him the truth.

“If she said that I was college material, then by God, I must be college material,” Thornton said.

He was.

After enrolling at Alexander City State Junior College, he went on to earn a Bachelors of Science Degree in Fine Arts at Alabama State University.

He taught art for four years at Vestavia Hills High School before a budget-related layoff pushed him into entrepreneurship.

He started picking up freelance jobs and knocking on doors to see if he could repaint a company’s sign between gigs.

He reached out to the father of former students of his and used that connection to land the job painting signs for Coca-Cola in 1979.

In four months, the company promoted him to manage the whole department, but Thornton didn’t stop thinking about the desire to own his own company.

He remembered a conversation he had with a man he met randomly while visiting relatives in Chicago. That man was Herman Petty, the first Black owner of a McDonald’s franchise in the company’s history.

He had opened the store Dec. 21, 1968, the same year Thornton was struggling to make it at as one of few Black people at a majority white school, but the thing Thornton couldn’t stop thinking about was Petty’s restaurant.

“One thing I couldn’t get out of my head was the number of white patrons who frequented this business,” Thornton said. “I asked, ‘You think they would do that in Birmingham, Alabama?”

Petty gave him a simple answer: yes, brand recognition.

So after saving money he earned from years of work with Coca-Cola, Thornton went through McDonald’s process of becoming a franchise owner. He trained for a year and a half, and in July 1992 opened his first store.

On opening day, he said white owners of other McDonald’s franchises walked into his restaurant and said, “We’ll own this in six months.”

Not only did he prove them wrong, Thornton incorporated Thornton Enterprises in 1992 and opened five additional locations under the umbrella, one of which he passed down to his son.

“And we still don’t have another black owner other than my son and myself,” Thornton said of Birmingham.

He’s had to overcome discrimination that to some would be unbearable, but Thornton persisted.

When children he wanted to play football with as a child would pick him last, he played with the team he was assigned to.

When would-be employers took one look at him and decided he was too young for a job after college, he applied elsewhere.

When an advertising manager for Coca-Cola drew a racist illustration in their workroom, he forced the man to draw it bigger.

The one attribute Thornton said he attributes his success to, the one thing no one could take from him is his dedication to hard work. He had 11 years of perfect attendance at Coca-Cola when he left as a full-time employee.

“There’s no substitution for hard work,” Thornton said.

The other important lesson he learned about being a business leader, he learned from Petty and Miss Nichols. That was how important it was to define himself on his own terms and stay consistent in that branding.

“What is it that you see when you see me,” he asks students in his institute. “And what is it that I see when I see you?”

Understanding the answers to those questions is a first step to success, Thornton said.

These days, he worries less about the Klan and more about police officers stopping his grandson.

Thornton said he warned him to keep his hands where officers can see them if he’s ever stopped “because I want my grandson to come home.”

“It makes you wonder how much we’ve really changed,” Thornton said.