At the time Virginia’s future political leaders put on blackface in college for fun, Dan Aykroyd wore it too — in the hit 1983 comedy “Trading Places.”

Sports announcers of that time often described Boston Celtics player Larry Bird, who is white, as “smart” while describing his black NBA opponents as athletically gifted.

FILE -In this Jan. 18, 1987, photo, Atlanta city councilman, Rev. Hosea Williams, in overalls, leads a march against efforts to keep Forsyth County in Georgia all white past counter-protesters near Cumming, Ga., as a crowd waves Confederate flags and jeer the marchers. (AP Photo/Gene Blythe)

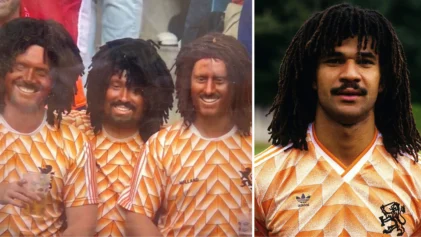

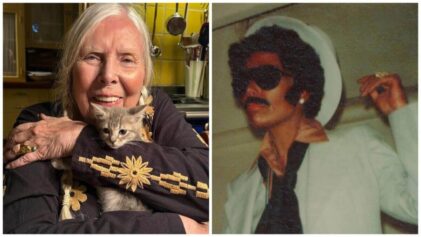

Such racial insensitivities ran rampant in popular culture during the 1980s, the era in which Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam and the state’s attorney general, Mark Herring, have admitted to wearing blackface as they mimicked pop singer Michael Jackson and rapper Kurtis Blow, respectively.

Meanwhile, Chicago elected its first black mayor, Michael Jackson made music history with his “Thriller” album, U.S. college students protested against South Africa’s racist system of apartheid and the stereotype-smashing sitcom “The Cosby Show” debuted on network television.

It would be another 10 years before the rise of multiculturalism began to change America’s racial sensibilities, in part because intellectuals and journalists of color were better positioned to successfully challenge racist images, and Hollywood began to listen.

“We are in a stronger position to educate the American public about symbols and cultural practices that are harmful today than we were in the 1980s,” said Henry Louis Gates Jr., director of the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University.

During the ’80s, college faculties and student bodies were less diverse, Gates said. Some scholars who entered college during the 1960s had yet to take on roles in which mainstream culture would heed their cultural critiques, he said.

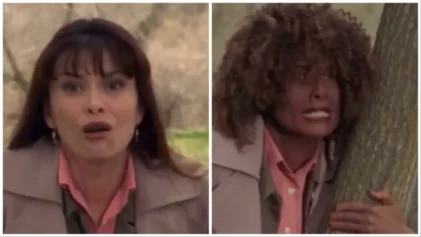

At the time Northam and Herring put on black makeup, Hollywood and popular culture still sent messages that racial stereotypes and racist imagery were comical and harmless, despite pleas from civil rights groups and black newspapers.

Herring was a 19-year-old University of Virginia student when he wore brown makeup and a wig to look like rapper Kurtis Blow at a 1980 party. Three years before that, white actor Gene Wilder darkened his face with shoe polish in the movie “Silver Streak” co-starring Richard Pryor. He used a stereotypical walk to impersonate a black person living in an urban neighborhood.

On television, viewers could see a Tom and Jerry cartoon featuring the character Mammy Two Shoes, an obese black maid who spoke in a stereotypical voice. The 1940s cartoon series was shown across several markets throughout the 1980s. Television stations ignored complaints from civil rights groups.

Elsewhere, Miami erupted into riots following the acquittal of white police officers who killed black salesman and retired Marine Arthur McDuffie in what many called a case of police brutality. President Jimmy Carter visited and pressed for an end to the violence, but a protester threw a bottle at his limousine as he left.

When Northam wore blackface to imitate Michael Jackson and copy his moonwalking skills at a 1984 San Antonio dance contest, television stations still aired Looney Tunes episodes with racially insensitive images using Bugs Bunny and other characters despite some controversial episodes being taken off the air in 1968.

African-Americans, however, had reason to be hopeful amid electoral gains. A year before, in 1983, Chicago became the latest city to elect a black mayor, Harold Washington, after activists registered 100,000 new black voters. That election, Jesse Jackson later said, paved the way for him to seek the Democratic nomination for president in 1984.

“It was out of that context that my own candidacy emerged,” Jackson said in the 1990 “Eyes on the Prize” documentary. Jackson lost the nomination to former Vice President Walter Mondale.

Two years after Northam’s moonwalk performance, the comedy “Soul Man” hit theaters. In the movie, Mark Watson, played by white actor C. Thomas Howell, takes tanning pills in a larger dose to appear African-American so he can obtain a scholarship meant for black students at Harvard Law School. The movie drew a strong reaction from the NAACP and protesters to movie theaters.

Still, “Soul Man” took in around $28 million domestically, equivalent to around $63.5 million today.

Despite those images, new and popular black cultural figures also emerged, including Eddie Murphy, Oprah Winfrey and a young Michael Jordan. Black Entertainment Television, or BET, was founded in 1980 by businessman Robert L. Johnson, giving the country access to black entertainment using 1970s sitcoms and music.

But as Nelson George argued in his book “Post-Soul Nation: The Explosive, Contradictory, Triumphant and Tragic 1980s as Experienced by African Americans,” BET failed to counter negative images by relying on free music videos and investing little money in original programming. “Through this conservative strategy, BET prospered while offering little new to a community starved for images of itself,” George wrote.

In addition, the new black cultural figures rarely engaged in politics or spoke out against racial injustice.

Sometimes, stereotypes and comments did result in consequences. For example, CBS fired sports commentator Jimmy Snyder, known as Jimmy the Greek, in 1988 after he suggested in a television interview that black athletes were better because of slavery. The Los Angeles Dodgers fired general manager Al Campanis in 1987 for saying on ABC’s “Nightline” that blacks “may not have some of the necessities to be, let’s say, a field manager or perhaps a general manager” and they were poor swimmers.

In 1987, black demonstrators marched in all-white Forsyth County, Georgia, to protest the racism that kept blacks out for 75 years. They were promptly attacked by white nationalists hurling rocks and waving Confederate flags. The shocking images sparked national outrage and led Oprah Winfrey to air an episode of her then-5-month-old syndicated talk show from the county.

“What are you afraid that black people are going to do?” Winfrey asked the audience.

“I’m afraid of them coming to Forsyth County,” one white man told her.

Today, Gates said, people can no longer claim ignorance. While it should have been understood that blackface was offensive during the 1980s, one might have had to go to the library to learn exactly why, he said.

“We also have more records digitized,” Gates said. “The access to archives is larger, and we have more diversity in the media so we can say these images are painful … and why we shouldn’t use them.”