Envisioned in 1971 by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), the Trans-African Highway (TAH) is a network of nine highways that would span a total of 60,000 km (37,282 mi) across the continent.(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Since the days before African independence, when the European colonizers controlled the continent, there has been a vision of building a vast network of highways connecting the African nations. Now, as the African nations make strides towards closer economic cooperation, common markets, and breaking down barriers to travel and trade in goods and services, this notion of a plan for interconnected roads linking the continent has much potential. However, there are impediments, but also potential help from China in making this long-term vision a reality.

Governments and financing and development agencies know of the substantial economic potential to linking the 54 African nations with their arbitrary boundaries, as Quartz Africa reported. Further, poor infrastructure means that transportation costs are 50 to 175 percent higher than in other parts of the globe. Africa is a vast land mass, perhaps more than many realize — larger than China, India, the contiguous United States, most of Europe and Japan combined. As Cobus van Staden wrote for the Jamestown Foundation, “African development hinges on a maddening paradox: its greatest asset — the sheer size and diversity of its landscape — is also the greatest barrier to its development. Landlocked countries are cut off from ports, and the difficulty of moving goods from country to country weighs down intra-continental trade,” he writes, noting that only 15 percent of African trade takes place within Africa. Further, the African consumer bears the burden of these challenges with higher prices due to corruption, tariffs and border delays, but. most important, the fact “that no streamlined transport route exists between West and East Africa — only a decaying and underdeveloped road and rail system which pushes up costs and drags down efficiency.”

In 1971, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) envisioned the Trans-African Highway (TAH), a network of nine highways that would span a total of 60,000 km (37,282 miles) across the continent. If the Trans-African Highway Network is undertaken, UNECA concluded, “Our continent will be placed in a strong position in term of the most positive factor for unity: the creation of physical bonds between our countries.”

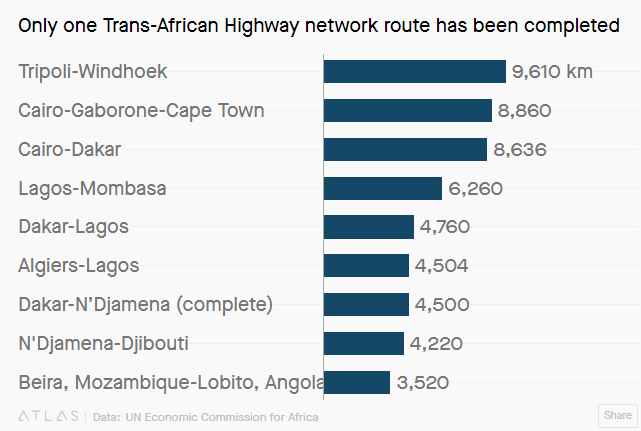

Some of the planned routes on the TAH include Tripoli, Libya, to Windhoek, Namibia, (9,610 km/5971 miles), Cairo, Egypt, to Dakar, Senegal, (8,636 km/5366 miles), and Algiers to Lagos (4504 km/2799 miles). Only one of these routes, the 4,500 km (2796 miles) Trans-Sahelian Highway between Dakar and N’Djamena in Chad has been completed with the help of China. Construction has been slow on the TAH, with different construction standards across countries, inadequate funding for maintenance and upgrades, crumbling of already constructed roads due to climate and terrain conditions, and civil conflicts cited as reasons. Further, borrowing limits imposed by the IMF have been an impediment to fast-tracking infrastructure development projects such as highways.

Source: Quartz Africa

With the Single African Air Transport Market initiated by the African Union; a Continental Free Trade Area covering 1.2 billion people with a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion which will pave the way for the free movement of business, people and investments and a Continental Customs Union; and plans for a common AU passport; the idea of a Trans-African Highway becoming a reality only makes sense. Already, inroads have been made in the expansion and integration of Africa’s port, road and rail network. In the absence of a developed highway network to facilitate trade across Africa, deficient infrastructure cuts economic productivity across Africa by 40 percent and causes traffic deaths. While it takes 19 days to ship a container from Singapore to Kenya, 20 more days are required to send those goods by truck from Mombasa and Nairobi via a single-lane road.

China stands to play an important role in the development of Africa’s transcontinental highway system. There is a rail component to the TAH, as van Staden noted, of which the first phase, slated to begin this year with a completion date of 2022, is a $2.2 billion upgrade to the 1,228 km (763 miles) rail line already linking Dakar and Bamako, Mali. The project is implemented by the African Development Bank’s Program for Infrastructure Development in Africa and is supported by the West African Economic and Monetary Union. In 2015, Senegal and Mali each signed their own agreement with the China Railway Construction Corporation. Senegal’s agreement amounted to $1.24 billion through a Chinese loan, while Mali finalized a $1.5 billion deal, as part of additional agreements including $8 billion railway link between Mali and the port of Conakry in Guinea.

It is no secret that China has dramatically increased its footprint in Africa. The Belt and Road Initiative, regarded by China as the largest project of the 21st century, is a massive multi-trillion dollar project encompassing infrastructure, transportation and energy, and a network of shipping lanes and railroads in 70 countries in Africa, Asia, Europe and Oceania. A number of Chinese projects in Africa, including railway lines, are under development with the promise of sustainable development. Chinese assistance may help expedite the realization of Africa’s dreams in uniting the continent by highway and rail, and precipitating economic growth. At the same time, Africans will be faced with asking hard questions regarding an increased Chinese presence (and military presence) in the motherland, the influence and control of foreign nations such as China over the continent, the sovereignty of African nations and foreign debt. With the Trans-African Highway, as with everything, there are costs involved.