Trayvon Martin. Michael Brown. Korryn Gaines. Eric Garner. Freddie Gray. Natasha McKenna. Tamir Rice. Rekia Boyd. Philando Castile. Stephon Clarke.

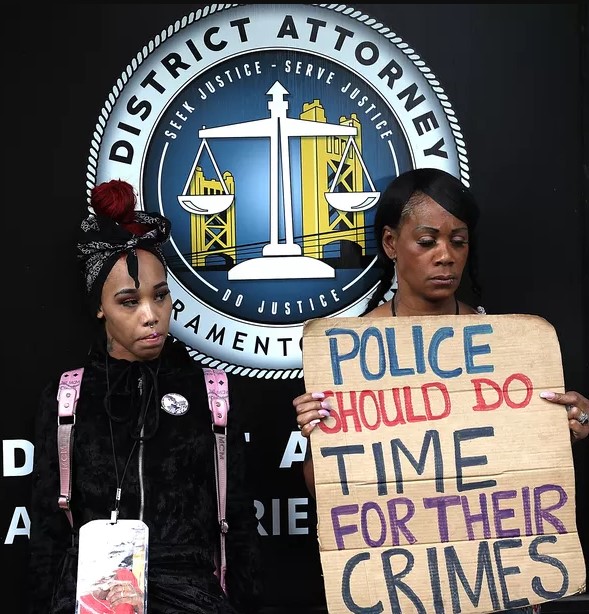

This is just a handful of the hundreds of black men, women and children in the United States in the past six years who have died at the hands of someone in law enforcement — or a person acting in that capacity. In most cases, a prosecutor’s decision not to prosecute because of a badge or their complexion allowed the killer to walk free.

Washington civil rights attorney Barbara Arnwine said since the acquittal of Trayvon’s killer, George Zimmerman, in 2013, and the subsequent non-prosecution of Officer Darren Wilson, who shot and killed Michael Brown the following year, there has been intense public scrutiny on prosecutors.

“The most important thing that has happened in the past four years has been the radical change in public awareness and perception,” said Arnwine, president and founder of the Transformative Justice Coalition. “Since Trayvon’s death, prosecutors have been challenged publicly by Black Lives Matter activists and others.

“What Shaun King and the Real Justice PAC is doing is important and will continue because Color of Change and Black Lives Matter have been pushing the issue. This is not low-hanging fruit. It’s an achievable goal. It’s something people can actually make happen,” Arnwine said.

In this election year, with midterms less than 100 days away and a resistance movement ignited by opposition to President Donald Trump and fueled by liberals, progressives, and millennials, there is what Arnwine and others say is a groundswell of activity to support and finance the election of district attorneys who are committed to shattering the status quo.

The hope is that after November, a new cache of district and state attorneys will join Larry Krasner in Philadelphia, Kim Ogg in Houston, Brooklyn’s Eric Gonzalez, and Nueces County’s Mark Gonzalez in Texas who are already putting their reformist stamps on the offices they oversee.

Krasner came into office on Jan. 2, 2018, with a bang. Since his election, he has detailed new policies aimed at mitigating mass incarceration; stopped seeking cash bail for those charged with low-level crimes; instructed his staff to incorporate the cost of incarceration into their sentencing recommendations; is offering plea deals with shorter prison sentences; and released the names on a secret list of 29 police officers who are accused of lying, bigotry, racism and other problems and are not to be called to testify.

Krasner fired 31 staffers during his first week, including trial lawyers, supervisors and homicide prosecutors, to implement a culture change. And since his arrival, about 80 prosecutors have resigned, retired, or been dismissed.

Vox’s German Lopez wrote a story recently about the quiet movement taking place in response to public demands for change.

“In Durham County, [North Carolina], Satana Deberry, a former criminal defense attorney, won her Democratic primary on a platform promising to oppose cash bail, hold police accountable, and resist the war on drugs — all key progressive demands for the criminal justice system,” he wrote. “Since she’s so far not facing another challenger in November, her primary victory means she should become the next district attorney for Durham County, barring a write-in campaign.”

And in Pitt County, N.C., defense attorney Faris Dixon also won in the Democratic primary. He has expressed support for the formation of a conviction integrity unit to review closed cases and ensure that defendants were not wrongfully convicted; expanding the use of drug courts in the region; and creating more transparency from the DA’s office. But Dixon faces a Republican candidate in November, so his position isn’t a sure bet yet.

“These may seem like minor local elections, but they are exactly the kinds of races that need to happen to significantly change the criminal justice system,” Lopez said. “These prosecutor offices are perhaps the most powerful in the criminal justice systems — helping decide who goes to prison, for what, and for how long.

“And since the great majority of people in jail and prison are held at the local and state level, district attorneys (who enforce state laws) have the biggest role where the bulk of criminal justice action happens in America.”

Law enforcement and prosecutors in a number of cities have been forced to respond to public demands and pressure. In several cases, voters have taken matters into their own hands. The best examples Arnwine said she can think of of activists and a frustrated populace using that anger to effect change, are Chicago and Cleveland.

Millennial activists from groups like the Chicago chapter of Black Youth Project 100, Assata’s Daughters, and Project Nia launched an effort to defeat Cook County State Attorney Anita Alvarez through protests of her reelection events, held teach-ins and educational forums, and drummed up support on social media, while other groups took over trains and engaged in constant and relentless protests and demonstrations.

“Anita [Alvarez] was the state attorney when a Chicago police officer killed LaQuan McDonald. She may have also participated in the cover-up,” said Arnwine, who was executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law from 1989 until 2015. “And in Cleveland, people were disgusted with the DA [Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Timothy McGinty] because of what happened to Tamir.”

McGinty refused to press charges against Tamir’s killer and added insult to injury by his haughty response to demonstrations and outrage by saying that the Rice family was exploiting Tamir’s death for financial gain and blaming the young boy for his own death. Alvarez waited 13 months until video of the shooting emerged before charging the cop who killed McDonald. The murder trial is underway now.

Tamir, 12, was shot and killed by a police officer while playing with a toy gun in a park near his home.

During his four years as prosecutor, some of Cleveland’s most notorious, highest-profile police-involved killings took place, but McGinty almost always declined to press charges or hold officers accountable. In November 2012, Cleveland police Officer Michael Brelo took park in a high-speed police chase of a car that had backfired and caused officers to mistake the sound for gunfire. More than 100 cops and 60 cruisers responded, and when the car stopped, Brelo stood on the hood of the vehicle, occupied by Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams. The cops shot 137 bullets into the car at the unarmed couple. Brelo fired some 49 of those shots, but he was declared innocent of manslaughter after a four-week bench trial.

McGinty was booted out in 2016 after influential Black community leaders, Black Lives Matter activists and other campaigners, church leaders and concerned residents mobilized voters and solidly backed challenger Michael O’Malley, a former Cleveland councilman and assistant Cuyahoga County prosecutor.

“After Tamir was killed, we saw a really growing awareness as people grew increasingly upset about prosecutors refusing to indict cops. In the past, people didn’t pay much attention, but this has incited a revolution and I expect it to continue,” Arnwine said.

Kami Chavis, a professor of law at Wake Forest University and a former assistant U.S. attorney in the District of Columbia, said that while she agrees prosecutors possess a great deal of unchecked power and enormous discretion in the cases they handle, she believes that creativity and imagination can have a profound impact on criminal justice.

“They need to recognize that there are a lot of different options than jail,” said Chavis, director of the Criminal Justice Program at Wake Forest University School of Law and associate provost for academic affairs. “For people running on a reformist agenda, no one should be confused that they aren’t tough on crime. Don’t think they don’t care about law and order. They recognize the inequalities that exist and are committed to treating people fairly.

“I don’t think the criminal justice system should be dismantled, as some suggest. We need to understand critics’ concerns and pay attention to concerns Black Lives Matter activists talk about. If a wide swath believe that the criminal justice system is illegitimate, this will cause many more problems.”

Former prosecutor Yvette McDowell said the fact that Americans are still grappling with the disparate treatment of people of color, racism and police brutality is sobering.

“How many times have we had these conversations?” she asked. “It’s been happening for decades and begs the question of why do these problems still continue? It shows that these discussions have not been impactful and that overall things have not changed.

“Those of us in law enforcement talk about this all the time. Here we are, 20 years later and we’re still talking about it. I don’t know if this [the current reformist drive] is a movement. If it’s a movement, it’s taking an awfully long time.”

But McDowell, a Bakersfield, California, native, who was a prosecutor with the city of Pasadena from 1995 to 2008, said activists for civil rights and other causes who came before have left a blueprint with which to fight back against injustice, dirty cops, indifferent judges and a system that unfairly targets Black people.

“This system offers impunity for the oppressors,” she said. “Dr. King said the oppressors will never give up power easily. Dismantling the criminal justice system will never happen. If [people] abstain from involvement in the political system, they’re putting a noose around their neck. You put them in, you vote them out. Dr. King and Malcolm X preached about the power of the ballot box. Why are we not taking heed to what they taught? There are so many examples of those who became politically active.”

Alicia McGraw, a veteran who most recently worked with the National Park Service as a park ranger, said she began working with the Real Justice PAC about three months ago.

“I want to make a contribution because this criminal justice thing has sparked a passion in me,” said McGraw, a Las Vegas, Nevada, resident. “I was recently online reading about the DA in Philadelphia, and I [was] shocked, shocked by his memo. I thought it was groundbreaking with the decision to no longer arrest or prosecute any marijuana cases, a diversion program for [people with] drug issues and having prosecutors lay out and tally up the cost of prosecuting people.”

“He also released the names of crooked cops.”

McGraw said she doesn’t believe in the death penalty and also believes that Black communities are policed too harshly.

“One of the things coming out of all the incidents we’re seeing around the country is that we have a very corrupt system. We have more crooked cops than honest ones. You can’t have a corrupt system if somebody tells. If somebody tells, it will stop. We need to start over.”

McGraw said the political action committee is working to elect Assistant U.S. Attorney Rachel Rollins in Boston’s Suffolk County and Wesley Bell in the St. Louis County prosecutor’s race.

“Ninety percent of district attorneys [ran] unopposed in the last election cycle,” she said. “You have old white men, white men in charge. And when we go before a judge, it’s usually a white judge. At the grassroots level, in every state, they’re getting people to do the research of who the DAs are, what they stand for, and compile a database.”

“DAs have the power to say who gets indicted. I don’t know how to change that. How is it that DAs are quick to indict a cop killer but don’t do it to one who kills a child or unarmed Black people?”

Shaun King, a social justice advocate and a reporter with Intercept, an online news publication, helped found the Real Justice PAC earlier this year, which, according to its website, “works to elect reform-minded prosecutors at the county and municipal level who are committed to using the powers of their office to fight structural racism and defend our communities from abuse by state power.”

Prosecutors, King contends, are the most powerful elected officials in the country, with broad discretion to either reinforce or reform structural racism in the criminal justice system. The PAC is raising $1 million to finance races during this election cycle.

While retired Police Chief Norm Stamper agrees with King and others that prosecutors have enormous power, he explained that he is cautiously optimistic about the prospects of reformist district attorneys turning around what he’s often criticized as a corrupt, unresponsive, and moribund criminal justice system.

“There is a real strong case to be made for the power prosecutors hold, but police officers play a very important role too,” said Stamper, who was in law enforcement for 36 years, during that time heading the Seattle and San Diego Police departments. “Call it the politics of prosecutors. You cannot divorce politics from prosecutors. Prosecutors will tell you that they’re objective and professional and that their decisions are based on law, not pushed by politics. It’s the last argument they will give you and the first defense of their actions.

“Prosecutors don’t want to antagonize law enforcement. They need the police chief to help them in getting their projects and programs passed and they need police officers to cooperate.”

Stamper said the origins of police departments still inform the way they deal with Black and Brown people, adding that any DA reform must be accompanied by corresponding changes in police departments.

“When they were formed, they lined up in exactly the wrong way. Then, public safety was serving as slave catchers and enforcing Jim Crow,” he said. “Generally, officers are working-class, blue-collar — too many of whom exhibit racism, sexism, homophobia and every kind of bigotry. This really picked up steam in the ‘60s with antiwar and civil rights demonstrations. These protesters were pitted against police officers, and they become more and more entrenched against young people and people of color.”

Stamper said the way officers act is not just a function of the culture, but also the power they wield which makes them feel as if they can do and get away with whatever they want.

“It’s an arrogance that afflicts too many officers,” he said. “It causes them to believe that they’re above the law. What we’re facing from institutions in Seattle, San Diego, the NYPD, and elsewhere is an undercurrent of racism and abusive practices that lead to excessive force and lethal force.”

“I’ve made the case in my book, “To Protect and Serve: How to Fix America’s Police,” that it’s time to restructure the institution,” Stamper said. “You hear about bad apples, but it’s time to recognize that if we continue to have incidents and call them bad apples we need to look at the barrel. The very structure and organization of police departments is dysfunctional.”

A paramilitary, bureaucratic structure stands in the way of meaningful reform, he said, necessitating the reengineering of a new culture.

“We need radical reform, meaning fundamental change, restructuring from the ground up, turning things upside down. I try to be honest and respectful, but it does no one any good for the system. Unless and until we’re willing to give people control and put them in the driver’s seat, nothing will change,” Stamper concluded.