Lindsey Beitz plays with Micke at Weccacoe Playground in the Queen Village neighborhood of Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Jacqueline Larma)

PHILADELPHIA (AP) — For generations, children would play kickball, hide-and-seek and jump rope on a stretch of concrete at Weccacoe Playground, unaware the remains of 5,000 black Philadelphians were buried 18 inches beneath their feet. Now, a portion of that playground will become a memorial to the dead.

Last month, the city announced plans to develop a section of the playground into the Bethel Burying Ground Historic Site.

“This is an opportunity to fix something that fell off of our radar, and it’s a teachable moment for these young children,” said Leslie Patterson-Tyler, whose husband, the Rev. Mark Tyler, is pastor of Mother Bethel AME. Her two daughters learned to swing at the playground when they lived in the neighborhood, she said. “It’s already a gathering place, so let’s continue to gather in this place and talk about what was.”

In the 1800s, no African-Americans could be buried in cemeteries within Philadelphia’s city limits. The dead could be buried at potter’s fields like Washington Square, but the city forbade any tombstones to mark those interred there.

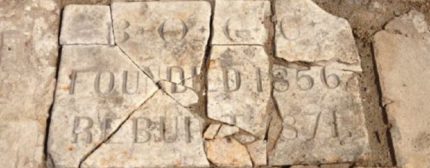

So when Richard Allen, a freed slave who founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church, sought to buy land for a burial ground for his church members in 1810, he had to search outside the city’s boundaries. The Mother Bethel Burying Ground was established that year on parcel of land a half-mile south of the church, in what was then called Southwark, a former 17th century Swedish settlement in an area the Lenape tribe referred to as “Weccacoe.”

After burials ceased in 1864, the graveyard fell into disrepair. The church sold the site to the city in 1889, and it was developed into a park.

As congregants with connections to the burial ground passed away, so did the memories of its existence. The park transformed into a playground called Weccacoe, and the neighborhood transformed into the Queen Village section of the city.

In 2008, historian Terry Buckalew doing research for a documentary on 19th-century black activist Octavius Catto when he stumbled onto references to Bethel Burying Ground. He knew of the church, but couldn’t place the burial ground.

“It basically had been lost to history,” he said.

He began collecting data on those buried there and writing biographies in an online project.

“I wanted people to be able to relate to who’s there. Many are former slaves, first-generation free blacks. I wanted to be able to say, ‘Here is a woman who was a single mom and ran her own business,'” he said.

Around 2011 he said he learned about a plan to renovate the playground. Buckalew reached out to the city, to the Queen Village Neighborhood Association and to Mother Bethel Church about his findings.

Archaeologists in 2013 determined at least 5,000 people were interred there, just 18 inches below the surface, Buckalew said. It’s likely many more are there, as the remains appeared to be stacked in three layers.

A committee and coalition were formed and after years of meetings, plans were hashed out to create a memorial at the site. A well-used community center will be dismantled to make way for the memorial.

“Like any neighborhood, we lament the loss of an accessible meeting space, but in this case it’s the loss of a space for all the right reasons,” said Eleanor Ingersoll, president of the Queen Village Neighborhood Association.

She said she’s been impressed with how inclusive the process has been, and is focused on keeping the public as involved as possible.

Kelly Lee, the city’s chief cultural officer, said they are more focused on getting the memorial right than moving quickly. The city will conduct community outreach to get input on what it should look like.

“At the end will be a memorial the whole city can be proud of,” she said.

Stephanie Gilbert’s family has been in Philadelphia since the 1600s. Her 4th great-grandfather was Clayton Durham, who worked with Allen in founding the AME church, and through genealogy research learned that his son James Durham was buried at Bethel, as well as other relatives.

She hopes the memorial will give visitors a better sense of Philadelphia’s free black community.

“They were part of very different kind of liberation movement,” she said. “They were fighting for careers and access to things they could afford but were kept out of.”

For Rev. Tyler, the memorial should be something that invites children in, that prompts thought-provoking questions so they ask their parents, “Why is this here?”

“I think that would be a wonderful way to honor the ancestors who are buried there,” he said. “To help these children write a new and better American story.”