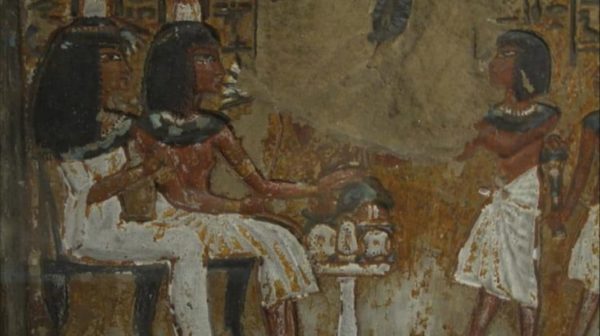

On a reported visit to Egypt, fifth century BCE Greek historian Herodotus, surprised by the women’s position in the society, recorded. “Women attend market and are employed in trade, while men stay at home and do the weaving.” The Egyptians, he concluded, “in their manners and customs seem to have reversed the ordinary practices of mankind.”

In a recent CNN article, Egyptologist Valentina Santini said, “The women of ancient Egypt — the mighty and the modest — were considered equal to men” Santini added, “They could divorce. They could own property. They had many rights that women in subsequent civilizations didn’t have.”

The subsequent civilizations Santini is likely referring to are ancient Western civilizations such as Greece and Rome, where women were relegated to second-class status. Greek and Roman women were prohibited from owning or inheriting property. European women in the Middle Ages lived under similar restrictions. Although Santini did not address other ancient African civilizations, there’s a plethora of scholarly work that has tied ancient Egypt culturally to sub-Saharan Africa. Numerous historians have highlighted some of the ancient Egyptian customs that are seen in other pre-colonial/pre-Islamic cultures throughout the African continent. The empowerment of women in domestic and in public domains is one such tradition.

In his book “The Cultural Unity of Black Africa” Senegalese scholar Dr. Cheikh Anta Diop argued that there exists a cultural continuity throughout sub-Saharan African cultures. He specifically points out the status of women, stating, “The African woman, even after marriage, retains all her individuality and her legal rights; she continues to bear the name of her family, in contrast to the Indo-European woman who loses hers to take on that of her husband.”

Aside from being empowered in marriage, precolonial African society had several avenues for women to exercise power. Throughout African history we have numerous examples of woman as queens who ruled, warriors who shed blood, and traders and merchants who built immense fortunes.

Vanderbilt professor Dr. Sandra Barnes, posits that “women in Africa were “one of history’s most politically viable female populations.” Queens such as Egypt’s Hatshepsut and Ethiopia’s Makeda (thought to be the biblical queen of Sheba) were known for using their leadership and wisdom to protect, expand, and enhance their nations.

Some African women were soldiers or held leadership roles in the military. Warrior queens such as Queen Yaa Asantewa of the Ashanti people, Queen Nzinga of the Matamba, and Queen Amina of the Hausa demonstrated military skills that rivaled their male contemporaries. These women led military campaigns that embarrassed empires. Interestingly, the fictional Dora Milaje warriors who protect King T’Challa — The Black Panther — in comic books and on screen are based on the so-called

“Dahomey Amazons,” properly known as the Ahosi (king’s wives) or Mino (our mothers) in the Fon language. The Fon were the people of the Kingdom of Dahomy (1600 until 1894), which was located in what is now the present-day Republic of Benin.

Certainly, not all African women were queens, chiefs, or warriors. Dr. Tarikhu Farrar, anthropology professor at Holy Names University in Oakland, California, says in his article The Queenmother, Matriarchy, and the Question of Female Political Authority in Precolonial West African Monarchy that “using the status of royal and aristocratic women as an indicator of the status of women in general could result in a relatively inaccurate portrayal of the overall status of women and of prevailing gender relations.” However, there is evidence that even common women had rights above any known in the Western world at the time.

In the book “African Women: A Modern History,” French author Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch explains that in West Africa, women were artisans who travelled far and wide to sell their goods. She notes that though East African women were not thought to be as active in trade, they were also involved in the trade of livestock and foodstuffs. In some parts of the region, the food could not be touched nor the livestock sold without a woman’s permission.

All this does not mean that Africa was an utopia of gender equality. Dr. Farrar noted that men and women did have different spheres of influence in African societies and that most leadership positions were held by older men, But it does suggest that African women were valued in ways not seen in most places outside of Africa.

Many modern-day African women are not enjoying the same level of freedom as their ancestors. This begs the question if ancient African societies valued women so much, what happened? Why did some communities in the diaspora reverse course and decided to subjugate women in a way that seems foreign to African traditions?

Many aspects of colonialism resulted in reduced public roles for African women. Dr. Ambe Njoh, professor of Environmental Science and Policy at the University of South Florida, wrote in his book “Tradition, Culture, and Development in Africa,” “Most of the socio-economic and political problems which African women face have their roots in European colonial development policies, which were designed to discriminate against women.” He notes that beginning in the colonial era, women were barred from trading, attending school, holding jobs, or participating in the economy in any way.

“Colonial rulers erased the balance that women provided in the political structures of African Societies by systematically preventing them from any participation in the new political order,” wrote Dr. Toyin Falola in the book “Women’s Roles in Sub-Sharan Africa.” European colonizers would avoid discussions of political matters with African women, even the queen mothers, who they often referred to in historical documents as “sisters” of the men in power. Post-colonial governments continued with policies that suppressed women’s traditional authority.

Furthermore, as Europeans took control of African land and agriculture, the perceived value of women’s contribution society was greatly reduced. In an article titled Women and Development in Africa: From Marginalization to Gender Inequality, the authors argue that the “establishment of commercialized agriculture also contributed to the loss of women’s economic power. In Africa, commercialization begun under colonialism, often led to the granting of government titles to the land. Consequently the effect was to transfer farmland that had been controlled by women to [white] male ownership.”

Adoption of foreign cultural and religious values may have also helped changed the way African women were valued. In a paper about the impact of religion on women in African society, Wenpanga Eric Segueda, a writer from Burkina Faso, wrote that in contrast to traditional African religions, Christianity and Islam demanded a lower status for women. He notes that “Islamic and Christian teachings led Africans to deny their own perceptions of things, viewing them as primitive, backwards, and worthless,” a perception that was encouraged by those touting the new religions.

“Arabs, hence Islam, found a lot wrong with indigenous African norms, traditional practices and beliefs,” write the authors of a 2001 paper “The Impact of Religion on Women Empowerment as a Millennium Development Goal in Africa,” published by Springer Science+Media B.V. The researchers specified that “this was especially true with respect to gender relations in both the domestic and public spheres. Consequently, disciples of Islam wasted no time in altering these relations in the areas of the continent they successfully penetrated.”

Christianity had a similar impact on the status of women in African cultures. University of South Africa theology professor Matsobane J Manala says in his paper “The Impact of Christianity on sub-Saharan Africa,” that the religion “led to the demise of African customs, which it viewed as pagan and evil; the religion also led to the implementation of apartheid (to which it gave its theological support), and undermined the leadership role of women.”

As stated before, Africa was not free from gender tensions, and gender equity had not been totally achieved. But as the world moves towards the direction of gender equity, it’s important to know that the Western world was never a better example — despite how much it avows women’s equality and attempt to impose its conceptualization of it onto others. Though there may be specific Western concepts Africans can use to improve the status of women in relationship to men, traditional African cultures provide some great solutions for the world as well.