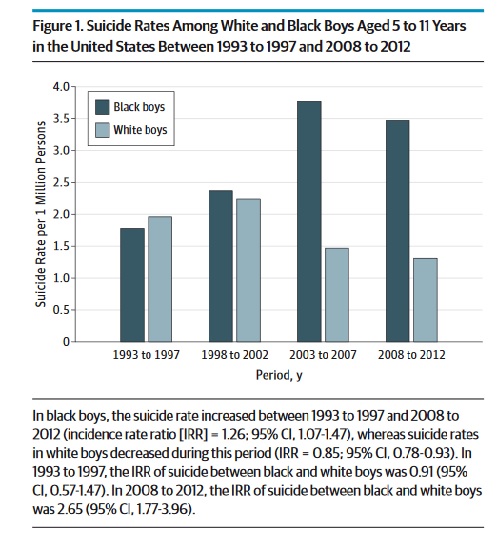

A 2015 study from Dr. Jeffrey Bridge of the Nationwide Children’s’ Hospital was one of the first to identify the disturbing new trend. Bridge’s work analyzed suicide rates for children ages 5 to 11. The results were dramatic: In the period studied, 1993 to 2012, the suicide rate for Black girls trended from 0.68 to 1.23 per million. In the same period, the suicide rate for white girls remained essentially the same — 0.24 per million. More disturbingly, while the report revealed a significant decrease in suicides for white boys during the relevant time frame, it found a steep increase in suicides among Black boys in the same period. In 1993, Black boys had lower rates of suicide than their white peers. But by 2012 the suicide rate for Black boys had doubled. The study found that white boys committed suicide at a rate of 1.31 per million, compared to 3.47 per million for Black boys.

What is happening? Why are Black children committing suicide?

Source: Graphic Taken from Bridge, et al., “Suicide Trends Among Elementary School–Aged Children

in the United States From 1993 to 2012,” available at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.692.4001&rep=rep1&type=pdf

One issue that impacts the increase in suicide is race. Bridge’s work noted, “Black children may experience disproportionate exposure to violence and traumatic stress and aggressive school discipline. Black children are also more likely to experience an early onset of puberty, which increases the risk of suicide, most likely owing to the greater liability of depression and impulsive aggression.” However, Bridge was careful to note that it was unclear if these factors were directly related to the increase.

Dr. Gene Brody, distinguished research professor of Human Development and Family Science at the University of Georgia, has also researched this issue. In a study co-written with colleagues, Dr. Brody found that perceived discrimination in late childhood and early adolescence could contribute to depressive symptoms in Black children. Additionally, he found that the risk for depression increased with an increase in family income. The study explained that higher income generally increases exposure to other racial groups, which also increases exposure to racial discrimination.

Could racism be the underlying cause of this deadly trend? To get more insight into this issue, Atlanta Black Star reached out to several mental health experts.

Dr. Rheeda Walker, associate professor and director of the Culture, Risk, and Resilience Lab at the University of Houston, has extensively studied suicide in the African-American community. She explained, “Our identity begins to solidify in adolescence. When a child or adolescent internalizes that she is ‘less than’ others or that he ‘does not belong’ because of the color of his or her skin, that can be psychologically damaging. Ideally, we want our children and youth to feel empowered — to feel that they can accomplish anything that they put their minds to doing. However, institutions and misguided individuals in our society aim to instill in us that being Black is unacceptable.”

Dr. Mia Smith-Bynum, associate professor of family science in the School of Public Health at the University of Maryland-College Park, elaborated. She explained, “The societal notion that Black children are not vulnerable or even human makes them confront race earlier. The societal attitudes that our children are not actually children begins early. That our children are suspended more often even in preschool is one example of that.”

“There is a type of racism for Black men and boys that is particularly harmful. It’s not that Black women and girls don’t face racism, but the stereotype of Black men as criminal and violent places amplifies threats to their personal safety. Black boys have less room to define themselves and their identity on their own terms and this can lead to significant mental health problems. The stereotypes are often used to justify police shootings in our public discourse.”

Smith-Bynum added, “Early to mid-adolescence is a vulnerable period. Between the ages of 10 to 15, there is a lot happening: You are going through puberty; your racial identity is developing. Our boys see so many negative racial stereotypes around African-American men. Our girls see toxic images of Black women in our media. When this cultural racism combined with a kid that is shy, has self-esteem issues, has difficulty regulating emotions, or is experiencing other kinds of distress — economic unpredictability, bullying — the risk is elevated. Race is not the only factor, and it’s usually not enough to cause suicide by itself. But there are some kids for whom it amplifies issues that are already existing.”

The experts were asked to explain Brody’s finding that higher incomes can lead to higher suicide risk for African-American children. Smith-Bynum said, “A parenting paradox for middle-class Black parents is how to capitalize on the benefits of their success without putting their children in settings that will destroy their self-esteem. Some white environments are hostile to Black children’s self-esteem, especially those that have very few Black children. In this instance, income does not necessarily help. It is not a given that income will protect, because kids in these environments are exposed to discrimination — it just an issue of volume and degree.”

Dr. W. Lavome Robinson, professor of clinical psychology at DePaul University, elaborated: “To the degree that a child interacts with other cultures and racial/ethnic groups, it increases the opportunity to experience racism. We must get rid of racism, but we must also equip youth who might be impacted by racism with coping skills so they won’t be overwhelmed.”

Dr. Smith-Bynum agreed, stating, “It is critical that parents of Black parents of Black children build up their children’s self-esteem about being Black. Parents should make sure that their children know Black history so that when they confront racism, they will know what they are confronting is not because of who they are or anything they’ve done, but because racism is something that has existed well before their time. Teach them in an age-appropriate manner. Give them strategies to help them deal with racism. Do not leave them to their own devices. Whether it’s telling a child to keep calm, or to exit a situation as soon as possible — give them practical tips on what to do in racist situations.”

The experts were asked if African-American children display depression and suicide symptoms that differ from those in other groups. Walker explained, “In general, mental health professionals and people in the lay community tend to associate suicide with depression. Across racial groups, anxiety is also a strong predictor, but in African-Americans, anxiety could be an even more important risk factor that is worth paying attention to with regarding to recognizing who could be at risk for suicide thoughts and be

When asked what Black parents should look for to determine if their children are at risk, Dr. Walker noted, “Parents can pay particular attention to changes or shifts in a child’s behavior or mood. Even if a child says that everything is OK, changes in mood that seem ‘out of the blue’ are worth paying attention to. It is important to reassure the child that the parent or caregiver is there to listen. Parents also have to be aware of their own depression and how they are managing stress. We cannot help our children if we have not first helped ourselves.”

What can parents do if a child is exhibiting suicidal tendencies? Dr. Smith-Bynum said, “Depression and anxiety are medical issues and need medical intervention. If you have diabetes, you can pray, but you should also go to the doctor.”

When asked about Black parents’ potential mistrust of the medical establishment, particularly psychology, Dr. Smith-Bynum had a clear reply: “Our community’s skepticism about medicine is well-earned. But a family should look into the skill set of anyone who provides care for a child and interview the providers to find a comfortable fit — look for someone who has experience working with African-American children and families. If you find a therapist that doesn’t work, find another. We are sometimes deferential to medical practitioners, but we don’t have to be. You don’t have to stay with a therapist you aren’t comfortable with. There are ways to find a person of color for a provider. Focus on depression as a health issue. It is true that, as a field, psychology has not always done right by Black people, but it is also true that depression is a serious medical issue. The stigma around mental illness should not outweigh your child’s health. It is literally a matter of life and death.”

Is there anything Black parents can do to reduce their child’s suicide risk? Smith-Bynum sai, “Parents can help their children by creating an open line of communication from an early age. Kids have to know that they can bring you their deepest, darkest secrets. In a high-achieving Black family, if there is a high-pressure environment, kids may not want to admit their feelings for fear being seen as a failure. They need to know that they are loved unconditionally and that there is nothing that can destroy your love for them. Hopefully, with that, they will feel comfortable coming to you when they are in distress. If they do, be sure to get them medical care.”

But Robinson noted that parents are not to blame and that all of society has a role to play in solving this issue. She said, “Schools have children at their command and offer enormous far-reaching promise. Children need more than reading, writing, and arithmetic — children, of all races — are coping with any number of things each day. Schools should infuse stress management and coping skills into the standard core. In this manner, all children will be given the tools for managing stress, to prevent adverse outcomes associated with racism-related stress and other stressors.”

Robinson added, “Suicide is devastating, but also preventable.” Because suicide is preventable, Black parents and others who care about Black children must challenge every person and every entity that works with Black children to do better. Black children deserve to live in spaces that support, rather than damage, their developing minds. With work, change is possible.