Contrary to the popular historical narrative, the Union’s effort to rein in the Confederacy and end the secessionist military rebellion now known as the Civil War was incomplete upon the iconic April 9, 1865, surrender of Robert E. Lee at a Virginia courthouse in Appomattox. While ending the conflict in Virginia, the legendary courthouse meeting between Lee and Union General Ulysses S. Grant prompted a series of subsequent surrenders in numerous Southern states and Western territories over the following months. On June 23, a full two-and-a-half months after Appomattox, the war finally came to its conclusion at the Doaksville settlement in present-day Oklahoma with the surrender of Stand Watie, the last Confederate general to lay down his arms.

Watie, a staunch Confederate whose loyalty and battlefield exploits had earned him the rank of brigadier general, was, perhaps, far too complex for our sanitized and more linear national historical narrative. He was a Native American, a Georgia-born Cherokee who commanded Southern troops in the Indian Territory consisting of battalions of Creek, Seminole, Cherokee and Osage natives. He was one of many natives who’d left their Southern lands behind three decades prior and entered the Oklahoma Territory by way of the infamous “Trail of Tears,” a series of forced relocations enacted by government authorities following the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

And, like a number of his native brethren, Watie was a wealthy planter and landowner who was accompanied on the western trail to the Oklahoma Territory by the sizable number of enslaved Africans he owned.

“What people need to realize is that slavery was not just Black and white,” said Dr. Arica L. Coleman, a nationally recognized historian of Black and Native American descent. Coleman, who has held numerous faculty appointments, is the author of “That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia.”

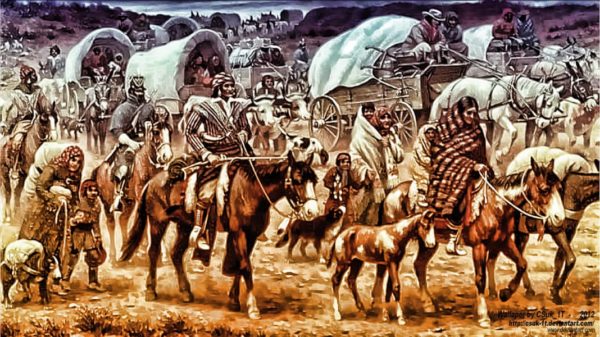

“Every time you see the pictorial representations, the iconography of the Trails of Tears, you only see Indians,” stressed Coleman, noting “the truth of the matter is they certainly didn’t leave their slaves behind.”

“We couldn’t ignore the fact that the Five ‘Civilized’ Tribes were actually slave states legally, where they did practice slavery,” said Paul Chaat Smith, associate curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Smith, a Comanche, noted the need to put the term “civilized” in quotations given its skewed 19th century Eurocentric application to the Southern-based Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations. The author of several books on Native American culture recently facilitated the museum’s “Ámericans” exhibit, which included information on the Trail of Tears, and a “Finding Common Ground” symposium exploring African-American and Native American relations.

While slavery was not practiced in native communities “in the same way that Mississippi or Alabama did in terms of numbers or being essential to the economy,” Smith stressed “they clearly took a position to support slavery, to enforce it in their laws and to actually fight for the Confederacy. So it would have been pretty hypocritical to talk about the role of Indian removal being part of these larger historical processes while ignoring the undisputed historical fact that Indian nations practiced and protected the institution of slavery.”

Although Native Americans, long before Waite and like many cultures, had practiced the enslavement of prisoners of war within and between their own cultures, they didn’t engage in racialized chattel slavery until the late 18th century amidst the increasing encroachment of white settlers. While this violent encroachment and its associated “civilization” efforts by whites impacted and influenced all of the five major groups, it was the Cherokee Nation that most actively engaged in and profited from Southern enslavement. Coleman has pointed out that by 1809, 600 enslaved Africans were held in the Cherokee nation alone, a number that increased to 1600 by 1835.

It was during the 1830s, in the aftermath of the Indian Removal Act, that the decade-long process known as the Trail of Tears occurred. Fueling the desire to claim the lands of those believed to be “godless savages” was the white settlers’ government-backed wish to expand the cotton industry, and the recent discovery of gold in parts of the South, particularly North Carolina. As a consequence, thousands of Native Americans were evicted from their common lands and forced to walk thousands of miles to designated Indian Territory in current-day Oklahoma, many dying from starvation and disease along the way.

Watie, one of a smaller faction of Cherokees who supported removal to the Western territory as the only way to preserve the Cherokee autonomy, was among those who signed the 1835 Treaty of New Echota that ceded native lands in Georgia in exchange for the Western territory. While he and the Africans he enslaved would make the move west in 1837, of the estimated 15,000 Cherokee in Georgia forced on to the trail in 1838, as many as 4,000 died.

Once in Indian territory, Watie and other native slave-owners resumed and even increased their heinous and profitable practice. “Slavery in Indian territory became a mirror-image of slavery in the white South,” said Coleman. She further explained there were already established slave codes within native territories dating back to the 1827 Cherokee Constitution, which stated, “The descendants of Cherokee men by all free women, except the African race, whose parents may have been living together as man and wife, according to the customs and laws of this Nation, shall be entitled to all the rights and privileges of this Nation, as well as the posterity of Cherokee women by all free men. No person who is of negro or mulatto parentage, either by the father or mother side, shall be eligible to hold any office of profit, honor or trust under this Government.”

“There were even Black Codes to keep in line the free Black populace, given there was a free Black population living among the Cherokees, Choctaws, Creeks and other groups,” added Coleman.

“I learned a narrative that said there were some really basic differences between the treatment of people enslaved by Native Americans and those enslaved by white people,” said Smith, of a popular yet questionable historical theme that emerged in the 1970s. “But more recent scholarship has really demolished that argument.”

While noting there were certainly variances in the way it was practiced by certain states and territories, Smith stressed that “one thing we now know about slavery that is well documented is that it really was about metrics, about money, about careful record-keeping given that slaves were very expensive” and a major investment. “So it’s not a valid argument to say that somehow enslavement under Native Americans was, to any significant degree, a kinder and gentler form of slavery.”

By 1860, there were 4,000 enslaved Africans living in the Cherokee Nation alone. Upon the Civil War, in 1861, Watie didn’t hesitate to join the Confederacy, given his common interest with the wealthy slaveholders of the South and his view of the federal government as the Cherokees’ primary displacer and enemy. He was pivotal in establishing the first Cherokee regiment of the Confederate Army known as the “Cherokee Mounted Rifles” and in securing early Confederate control of Indian Territory. Unwilling to acknowledge Confederate defeat upon Lee’s Appomattox surrender, Watie would ultimately close the epic military chapter of America’s most historic internal conflict by finally laying down his arms to Union Lieutenant Colonel Asa C. Matthews at Doaksville on June 23.

It is a little-known conclusion to a pivotal American event.

“This is why history is so important,” insisted Coleman, promoting the value of a more nuanced and accurate account, regardless of where the truth may take you. “When you say slavery was only Black and white,” continued Coleman, “it erases the other part of that story.”