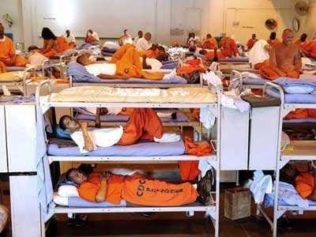

Kristan Morgan, 30, said staffers receive a radio and a set of keys when they’re assigned to guard duty. (Photo by Colin Hackley/USA TODAY)

Concern has grown among union officials as more and more civilian workers are tapped to step in as security guards across the U.S. Bureau of Prisons system.

Hundreds of teachers, counselors, cooks and even nursing staff were pressed last year to fill guard posts across the agency due to acute officer shortages and overtime limits, prison records obtained by USA TODAY revealed. The moves were made despite multiple warnings that the assignments, known as “augmentation,” put civilian employees at risk.

“It puts inmate safety at risk and our own security at risk,” said Kristan Morgan, a nurse who’s repeatedly been asked to pull guard duty in a cell block. “When we play officer, we are not equipped. We’re not familiar with the housing units … the inmates know exactly who we are and what our limitations are.”

Morgan, 30, said she often reports to duty in her scrubs and tennis shoes because there aren’t any extra officer uniforms laying around.

“I’ve been ordered to do it. I have no choice,” she told USA TODAY.

Despite a House panel directive advising the agency to “curtail its over-reliance” on the so-called augmentation, officials said the practice has become quite common at some federal prisons across the country. The assignments are only to be used in emergency operations, but some institutions have plumbers, budget analysts and commissary workers filling in as corrections officers at maximum-security prisons.

A sampling of work rosters at a prison facility in Coleman, Florida showed that almost 36 staffers, including teachers, laundry workers and a religious services staffer, were tapped for guard duty last year, the newspaper reported. This trend held true in Victorville, Calif., where John Kostelnik, chief of a local prison workers union, said 60 civilian staffers were assigned to guard posts.

The Bureau of Prisons hasn’t denied its over-drafting of civilian workers, however, arguing in a letter that all employees are considered “correctional workers first.” Although staffers are provided basic officer training as part of their employment, few are required to put the training into action before they’re assigned to guard duty.

“… We continue to hire staff at institutions around the country as needed to further the mission of the Bureau of Prisons,” the agency said in a statement.

Officials say the shortage of prison guards is only expected to get worse, as the Trump administration plans to cut an estimated 6,000 positions from the agency’s force. About 1,800 are guard positions. With that, the bureau will be forced to get even more civilian workers to fill-in, further upping the level of risk for both staffers and inmates.

The agency argued, however, that its staffing will largely remain the same, as most of the axed positions are already vacant. Still, union officials expressed concern over the risks these assignments pose to staffers’ safety.

“We have people who have literally never done this before,” Kostelnik said. “It’s quite scary. The whole system of (civilian reassignments) is a mess.”